Summary

In the past three decades, the Cambodian government has created national parks with little concern for local communities and Indigenous peoples. In practice, these large nature reserves have obstructed the recognition and titling of their traditional territories.

At the same time, powerful business interests affiliated with the ruling Cambodian People’s Party have benefitted from land concessions inside protected areas or are simply enabled to illegally extract resources.

This dynamic has led to a paradoxical situation in which 41 percent of Cambodia’s surface has nature reserve status, but the country boasts one of the highest deforestation rates in the world. Cambodia exemplifies how protected areas that are not community-led fail to benefit either people or nature.

Now, a new activity is competing with illicit economies in Cambodia’s forests: carbon offsetting. The government has energetically pursued a strategy to sell carbon credits in exchange for protecting forestland. By the first half of 2023, Cambodia had become a major supplier of carbon credits from nature projects: together with Peru, they represented 17 percent of the world’s output.

This report assesses the impacts on the rights of Indigenous people of Cambodia’s largest carbon offsetting project, the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project. The project is implemented jointly by the Ministry of Environment (MOE) and the conservation organization Wildlife Alliance (WA).

Human Rights Watch found that the REDD+ project conducted activities for 31 months before consulting Indigenous Chong people living in the area, violating their right to free, prior, and informed consent for the project. Project activities during those 31 months included crucial decisions on the management of more than half a million hectares of land, such as incorporating eight Indigenous Chong villages into a national park.

The decisions taken without adequate consultation with affected Indigenous peoples continue to impact their rights to this day.

Human Rights Watch interviewed Chong Indigenous families who described being forcibly evicted by MOE rangers, gendarmes, and WA staff from farmland they customarily relied on. In some cases, community members were arrested and detained for months without trial following the eviction, according to judicial records. Further, some Indigenous community members described being arrested and mistreated by patrols composed of MOE rangers, gendarmes, and WA staff while they collected sustainable forest products in the REDD+ conservation area. In two Chong villages, residents described WA staff and MOE rangers conducting arbitrary home searches to apparently deter collection of sustainable forest products.

The cases relayed to Human Rights Watch may not reflect the totality of such incidents.

At the time of writing, the REDD+ project did not have a benefit sharing agreement with any of the communities included in the project. Benefit sharing agreements are legally enforceable contracts that establish the percentage of project earnings that will be disbursed to communities.

WA responded that all their activities complied with Cambodian domestic law and that the project benefits local communities. The MOE spokesperson wrote to Human Rights Watch that “the sale of carbon credits has benefitted communities that were involved in the protection and conservation of natural resources.” WA wrote to Human Rights Watch that the project had built wells, toilets, a laterite road, two schools, and one health post, given scholarships to five youths to attend university, provided agricultural training to small landholders, and operated two eco-tourism initiatives that benefited local residents.

In interviews with Human Rights Watch, Indigenous residents and community leaders expressed concern about the confusing boundaries of the REDD+ project and its impact on their livelihoods – particularly farming and collecting forest products. Several said they wanted the project to treat them as partners, including by managing a part of the REDD+ project’s revenue and being able to lead their own conservation activities independent of WA. Community members also said they shared the goal of protecting forests and emphasized the REDD+ project should respect their rights while conducting conservation activities.

The Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project

Human Rights Watch conducted a two-year investigation into the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project. The nature conservation project administers more than half a million hectares across the Cardamom rainforest in southwest Cambodia, one of the planet’s 36 internationally recognized biodiversity hotspots. The rainforest is a habitat for the Asian elephant, the sun bear, and the clouded leopard.

The REDD+ project also includes 29 villages with more than 16,000 residents. Families in these villages are farmers, with a third of them completely dependent on agriculture. The REDD+ project’s stated aims are to protect the fauna and flora of the Cardamom mountains’ rainforest and to provide economic opportunities for these communities.

The REDD+ project is implemented by the MOE and WA. As the government institution in whose jurisdiction the project takes place, the MOE has oversight over all project activities and design. MOE rangers also have authority to conduct law enforcement operations inside protected areas, including within the boundaries of the REDD+ project.

In its correspondence with Human Rights Watch, WA defined itself as a “boots-on-the-ground, community-led conservationist organization.” Its chief executive officer also wrote that WA provides “legal support” to Cambodian environmental law enforcement. WA oversees and funds the Cardamom Forest Protection Program (CFPP), which pairs WA advisors with MOE rangers and gendarmes (colloquially known in Cambodia as “military police”) to patrol the Cardamom rainforest.

Wildlife Works Carbon (WWC), a for-profit private company that stated in 2021 that it had developed 20 percent of REDD+ projects on the global market, is an investor and a technical advisor to the project. Everland, a specialized for-profit marketing firm, advertises the project and brokers the sale of its carbon credits.

As of June 2023, the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project had issued more than 27.6 million carbon credits. Companies and private individuals purchase credits to offset an equivalent volume of their emissions, a practice known as “carbon offsetting.” Once a credit is used to offset emissions, it is “retired,” meaning it can no longer be bought or sold. As of June 2023, more than 5 million credits issued by the REDD+ project had been retired, though many more may have been purchased and are yet to be retired.

An official report stated that as of late 2021, the REDD+ project had made more than US$18 million from the sale of carbon credits, of which US$6 million were spent in the project. Then, in November 2022, the carbon marketing firm Everland brokered a deal with multinational corporations that committed to buy millions of tonnes of carbon credits from the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project.

Human Rights Watch requested up-to-date information from WA and the MOE about the revenue generated by the project’s sale of carbon credits in 2022, as well as a breakdown of how the revenues have been used, but they had not responded to these queries at the time of publication. According to WA’s website, agreements over revenue distribution have been concluded between WA, the Cambodian national government, and the Koh Kong provincial government. The REDD+ project does not have a benefit sharing agreement with any of the communities included in the project.

In the course of researching this report, Human Rights Watch has repeatedly urged WA to conclude benefit sharing agreements with local communities included in the project. In December 2023, WA published an “Open Letter to Stakeholders” on its website, and then later added to that letter an undated addendum titled “Benefit Sharing.” The addendum states the project spent a total of US$2,045,733 in 2023 in “community development activities,” and that the sum represented 36 percent of the “Annual Project Workplan” expenses, the remaining 64 percent being destined to forest protection activities. The addendum states that the project must also pay Verra, marketing fees, and Cambodian government authorities. The addendum does not state the overall revenue that the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project has generated, nor the percentage of that revenue destined to fund the Annual Project Workplan or “community development activities.”

Indigenous Chong People

Indigenous Chong people live in 11 of the 29 villages that were included in the REDD+ project, they have lived in the Cardamom mountains for centuries. Eight of these villages are located in Chumnoab, Pralay, and Thmor Donpove communes, forming the Chhay Areng valley in Thmor Bang district, Koh Kong province, and another three of those villages are located in O’Som commune, Veal Veng district, Pursat province.

In the past decade, Chong communities were threatened by the construction of hydroelectric dams. In the case of O’Som, the Stung Atay reservoir flooded a substantial portion of the commune, including important spiritual sites and farmland. In the case of the Chhay Areng valley, residents successfully fought back against the Steung Areng dam, but activists were persecuted by the government in retaliation for their organizing.

To date, none of these communities have been able to obtain communal land titles to protect their farmland, spirit forests, burial sites, and other communal land. The process to be recognized as Indigenous and gain a communal land title is onerous and complex under Cambodian law, and the vast majority of Indigenous communities across the country are yet to receive a title.

Verra’s Certifications

While implementing the REDD+ project, the MOE and WA are obligated to uphold Cambodian domestic law and meet the international human rights standards to which Cambodia is party. Additionally, the MOE and WA have committed to upholding three voluntary standards managed by Verra, a nongovernmental organization that offers certification in exchange for payment. These voluntary standards are:

- The Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), version 3.4, certifies the environmental integrity of the carbon credits issued.

- The Climate, Community and Biodiversity Standards (CCB), version 3.0, which certifies that projects uphold the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities.

- The Sustainable Development Verified Impact Standard (SD VISta), which certifies that projects benefit local communities in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Adhering to these standards may enable the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project to charge higher fees for its carbon credits.

Verra has a memorandum of understanding with the Royal Government of Cambodia to “support capacity building,” as Cambodia seeks to increase its participation in international carbon markets.

Of all private entities that offer certifications to carbon crediting projects, Verra is the largest, overseeing half of the global market. In 2023, several scientific studies criticized Verra for certifying projects that vastly overestimated climate benefits. Verra has denied the allegations.

Verra earns revenue based on the number of projects it certifies and the number of credits it issues for each of these projects. Further, the auditors that examine whether projects meet Verra’s standards are paid by the project developers who are being examined. Every aspect of what is described as an independent verification process is ultimately conducted by financially self-interested parties in the regulatory vacuum of the voluntary carbon market.

Findings

Human Rights Watch interviewed 91 residents in 23 of the 29 villages included in the project, reviewed satellite imagery, topographic maps, scrubbed social media for pictures and videos to corroborate accounts, and reviewed the project’s official documents and audits. In September 2022, Human Rights Watch began requesting information and responses from the entities involved in the REDD+ project’s design, implementation, auditing, certification, and marketing through letters, e-mails, and calls. Human Rights Watch also held an in-person meeting with Wildlife Alliance and Everland in New York.

Impact on Indigenous Peoples’ Right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent

According to project documents and WA’s correspondence, the MOE and WA began organizing meetings with affected communities to inform them of the REDD+ project in August 2017. Although these meetings were formally intended to be a process to gain the free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) of people in the 29 villages included in the REDD+ project, these meetings began 31 months after the project’s start date on January 1, 2015.

In correspondence with Human Rights Watch, WA maintained that the project was not in existence prior to 2018. However, WA’s own correspondence and that of Wildlife Works Carbon, its technical advisor for the REDD+ project, as well as the official reports about the REDD+ project submitted to Verra, describe significant project activities being conducted prior to the consultation meetings held in August 2017. For example:

- Wildlife Works Carbon told Human Rights Watch that they conducted a feasibility study, and that between 2012 and 2016, Wildlife Works Carbon wrote proposals to help find financing for the carbon project that WA and the government wanted to do in this area.

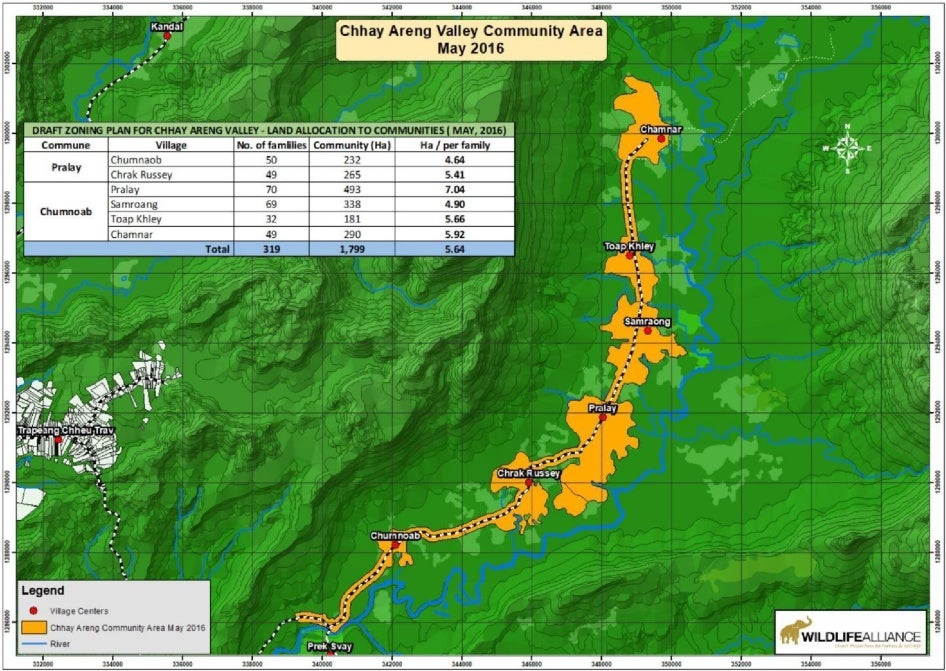

- WA wrote to Human Rights Watch that between October 2015 and May 2016, WA mapped individual plots of residential land and farmland in villages that are home to Chong Indigenous peoples in Chumnoab, Pralay, and Thmor Donpove communes.

- WA advocated for the creation of the Southern Cardamom National Park, and the Cambodian government created it in May 2016. WA wrote to Human Rights Watch that the creation of the national park was a “critical moment for a REDD+ project.” Eight Chong communities were enclosed in this protected area before their traditional territories were mapped and titled.

- WA began developing the REDD+ project in October 2016 and signed contracts with the Cambodian government to create the REDD+ project in February 2017, WA wrote to Human Rights Watch.

- According to the validation report issued by the auditing firm SCS Global Services in 2018, project activities were ongoing between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2017.

The information about the scope, impact, and benefits of the project imparted at the meetings that the MOE and WA began holding in August 2017 appears to have been inadequate, given that residents in several villages repeatedly told auditing firms and Human Rights Watch that they did not understand what the project does, how its boundaries would impact their farmland, or how they stood to benefit from the project.

Regarding the accuracy of the information imparted during these meetings, the REDD+ project staff initially told reluctant community members that the project would assist them in gaining land titles, only to later concede in a 2021 audit that the project could not in fact confer land titles or had any insight into when land titles would be granted to residents.

Neither auditors nor Verra properly investigated nor addressed these grievances raised by community members during audits.

SCS Global Services, the firm that conducted the validation audit, replied that “FPIC needs to be attained prior to the implementation of any project activities that affect property rights (statutory or customary) of stakeholders,” but “that the FPIC meetings began in August 2017, which is not prior to the start date,” and concluded their auditor’s professional judgment was in line with existing practice. The auditing firm Aster Global responded that the issue of whether FPIC meetings were held prior to the start date of the project was beyond the scope of the audit they were contracted to perform.

Impact on Indigenous Peoples’ Livelihoods

The flawed FPIC process, and, subsequently, flawed audits, have had profound effects for the rights and livelihoods of the affected Indigenous Chong people, who have faced criminal charges for farming and for collecting sustainable forest products.

Human Rights Watch documented cases of six families where WA staff together with MOE rangers, and gendarmes, evicted Indigenous people from farmland they cultivated. In none of the instances documented was there any indication that residents received alternative farmland, nor humanitarian aid or compensation, with serious impacts for these families’ livelihoods.

Given the way these evictions were conducted, Human Rights Watch concluded they constituted forced evictions, which are prohibited under international human rights law binding upon Cambodia and which WA has a responsibility to respect. WA has said that these were environmental law enforcement operations in conformity with Cambodian law; but an eviction process deemed lawful under Cambodian law may still constitute a prohibited forced eviction under international human rights law.

Human Rights Watch documented cases in which three residents who said they were evicted from the farmland they relied on were also prosecuted on criminal charges. In these cases, the men were also reportedly asked to sign statements that incriminated them without having had access to legal counsel. They were subsequently detained for nine months without trial, according to judicial records reviewed by Human Rights Watch.

In addition to the criminalization of farming, Indigenous residents have also faced arrest and detention for collecting sustainable forest products that do not lead to deforestation or forest degradation.

Chong Indigenous residents from O’Som commune reported being arrested by a patrol composed of MOE rangers and WA staff for collecting sustainable forest products in the conservation area of the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project, specifically while they tapped resin trees. Tapping resin trees is a traditional activity practiced by many Indigenous communities across Cambodia, and it does not lead to the tree’s destruction. The residents who spoke to Human Rights Watch alleged that they were mistreated by WA and MOE rangers.

Chong Indigenous residents in Chhay Areng valley told Human Rights Watch that WA staff and MOE rangers, sometimes also together with gendarmes, would arbitrarily search their homes. A government official told Human Rights Watch they had asked WA to stop “harassing poor people just for collecting forest products” in the Chhay Areng valley.

WA wrote to Human Rights Watch that “the residents of villages that are located inside the Project Zone can access non-timber forest products (NTFPs) inside the Project Area” and that “the Chong people have not lost access to resources as a result of the establishment of the SCRP boundaries.”

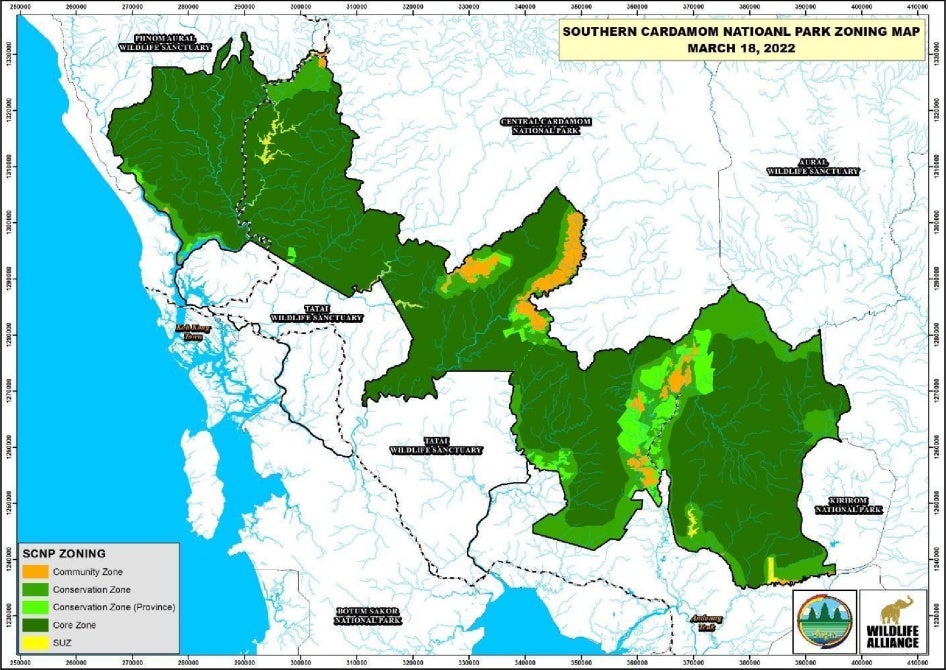

At the same time, the REDD+ project’s description submitted to Verra states that “the entirety of the Project Area will be within Core and Conservation Zones.” Under the 2008 Protected Areas Law, no collection of forest products is allowed in the “Core Zone.” On March 18, 2022, the MOE and WA concluded the zoning map of the Southern Cardamom National Park – which makes up most of the Project Area of the REDD+ Project – and they zoned most of the park as a Core Zone. By virtue of its design, the project restricts access to sustainable forest products for Indigenous peoples in a substantial area.

Response to Human Rights Watch Research

On June 20, 2023, after receiving a letter summarizing our preliminary findings, Verra informed Human Rights Watch that it was pausing the issuance of any further carbon credits for the project while it reviewed it. Verra declined to comment on Human Rights Watch findings while their review was ongoing, but noted Human Rights Watch’s recommendations in regards to Verra’s review of the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project would be “considered carefully” and “may be incorporated into Verra’s findings.”

Given that several of the concerns documented in this report had already been raised by community members during annual audits conducted since 2018, Human Rights Watch urges Verra to ensure its review provides effective redress for affected communities and individuals. Further, Human Rights Watch urges Verra to review its own processes to ascertain why they were unable to detect and ensure the remediation of the human rights abuses documented in this report.

On February 5, 2024, Verra wrote that it would take steps to improve the accessibility of its grievance mechanism in line with some of Human Rights Watch recommendations. These steps include allowing for grievances to be filed in different languages, conducting its own investigations into grievances on a case-by-case basis, and providing “entities filing grievances with relevant information throughout the process.”

In October 2023, after Human Rights Watch shared its final findings with WA and Everland, WA engaged an attorney at the law firm Foley Hoag LLP to “provide guidance regarding WA’s responsibilities under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.” WA anticipated that the attorney’s work would “range from assistance in creating a Human Rights Policy to counsel regarding operationalizing our commitments through effective human rights due diligence.” That October, the Koh Kong provincial government issued a document stating it would begin surveying land in Chhay Areng valley – the first step for residents in this predominantly Indigenous area to obtain land titles. However, this process, as currently foreseen, will not demarcate communal land.

In November 2023, WA committed to take several steps in response to Human Rights Watch’s preliminary recommendations, including:

- “to the extent that any Chong communities decide to pursue indigenous community land titling… provide technical and financial support for those efforts”;

- working with Chong Indigenous people to “establish, train, and support an indigenous Community Patrol team in the Areng valley”;

- “provide formal human rights training to all Cambodian government rangers and WA staff… with the assistance of the OHCHR [United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights]”;

- developing a “formal Human Rights Policy” and integrate it into their “existing Code of Conduct and Standard Operating Procedures”; and

- increase the number of grievance boxes available throughout villages included in the project.

In February 2024, Wildlife Works Carbon (WWC) wrote they “strongly refute HRW’s allegation that through Wildlife Works Carbon’s technical and financial support of the SCRP, WWC contributed to the human rights abuses that are alleged to have taken place during the implementation of the project.” Further, WWC wrote that “as part of WWC’s renewed commitment to working with Wildlife Alliance” they had “placed a WWC Cambodia staff member to be stationed on the ground” at the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project to increase WWC’s visibility of the project’s activities. Further, this “WWC staff member has assisted in creating a community-engagement strategy to manage community conflicts and grievances between MOE staff and community members.”

Key Recommendations for Verra’s Review of the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project

Human Rights Watch urges Verra to make issuances of new credits, retirement of existing credits, and renewal of accreditations for the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project, as well as listing of any new REDD+ projects in Cambodia on Verra’s registry, conditional on:

- Comprehensive remediation for individuals and communities adversely impacted by the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project, including through monetary compensation;

- Accountability for individuals involved in any human rights abuses perpetrated in the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project;

- Mapping and titling of Indigenous Chong communal land by the Royal Government of Cambodia in line with sub-decree no. 83;

- A new consultation process that upholds international human rights standards and best practice in relation to the right to free, prior, and informed consent, including by enabling residents to revisit the existing design, boundaries, activities, and project implementer of the REDD+ project;

- Conclusion of binding benefit sharing agreements with local communities and Indigenous communities; and,

- Formal recognition by the Royal Government of Cambodia in its REDD+ strategy of Indigenous ownership of the carbon stored in Indigenous territories.

Methodology

Rationale

There is growing interest in carbon offsetting projects by both governments and the private sector, including through a new mechanism contemplated under article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement on climate change. Forestry projects, including REDD+ projects, may supply a large volume of credits and many governments have begun taking steps to establish legal frameworks for domestic projects. This report seeks to contribute to the understanding of the human rights implications of these projects.

The Cambodian government is giving REDD+ projects a dominant role in its conservation strategy. Protected areas make up 41 percent of Cambodia’s surface. In September 2022, the Ministry of Environment announced that soon one-third of the country’s protected areas would be part of a REDD+ project, and that they aimed for all of them to sell carbon credits.[1]

Additionally, research on the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project provides an opportunity to assess whether certification organizations such as Verra can mitigate human rights risks in a jurisdiction, like Cambodia, where the formal recognition of Indigenous land rights is lagging, and rights abuses related to land are widespread and largely carried out with impunity.

Sources

For the elaboration of this report, Human Rights Watch relied on multiple sources. A Human Rights Watch research team visited locations within and near the Southern Cardamoms REDD+ Project (SCRP) and interviewed 91 people over the course of several research trips between April 2022 and November 2023. In total, the research team conducted interviews in 23 of the 29 villages included in the REDD+ project. In addition, the Human Rights Watch team made unannounced visits to the REDD+ project’s eco-tourism initiatives in Chi Phat and Steung Areng, and the agriculture training project in Sovanna Baitong. These visits were not coordinated in advance with WA.

The 91 people interviewed included 40 women, as well as three government officials (their exact titles are withheld for security reasons). All interviews were conducted in person (except for one interview conducted over the telephone) and in Khmer, either with the help of an interpreter or by a Khmer speaker. For the security of those interviewed, Human Rights Watch has assigned pseudonyms to all interviewees and withheld identifying details from their accounts.

All interviewees provided oral informed consent and were assured that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any question. Interviewees were not compensated. Some who traveled to meet Human Rights Watch researchers were reimbursed for the travel expenses they incurred.

In addition to gathering testimony, Human Rights Watch also reviewed documents made available by witnesses including birth certificates, land titles, commune and district registration forms, prison release forms, and micro-finance loan repayment schedules, among others.

Open-source researchers at the Human Rights Watch Digital Investigations Lab (DIL) verified videos and images posted on social media by eyewitnesses, victims, government officials, and journalists, and cross-referenced it with testimony and satellite imagery. Human Rights Watch has withheld the dates and links to the social media posts we analyzed to protect the identities of witnesses identifiable in these pictures and videos.

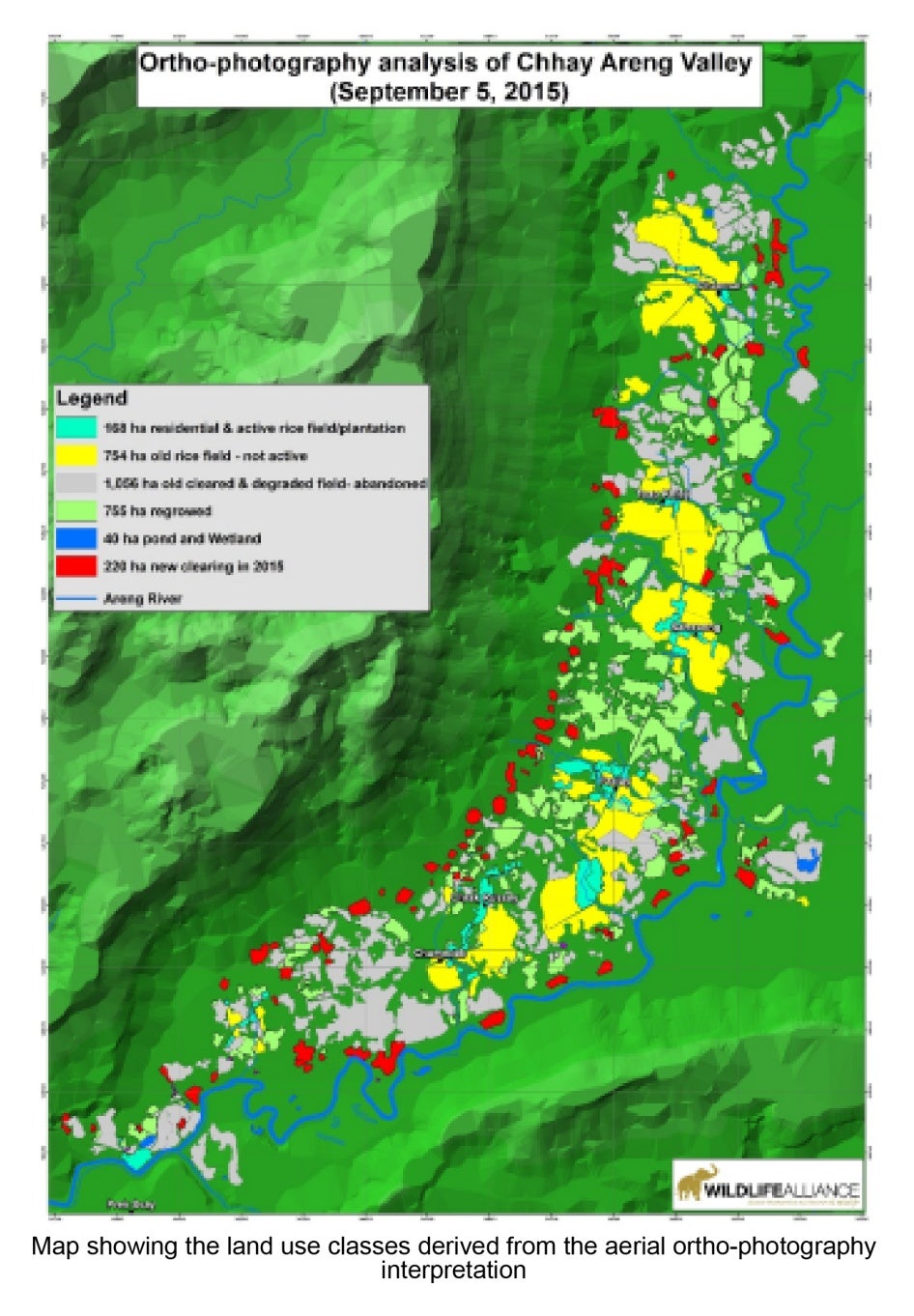

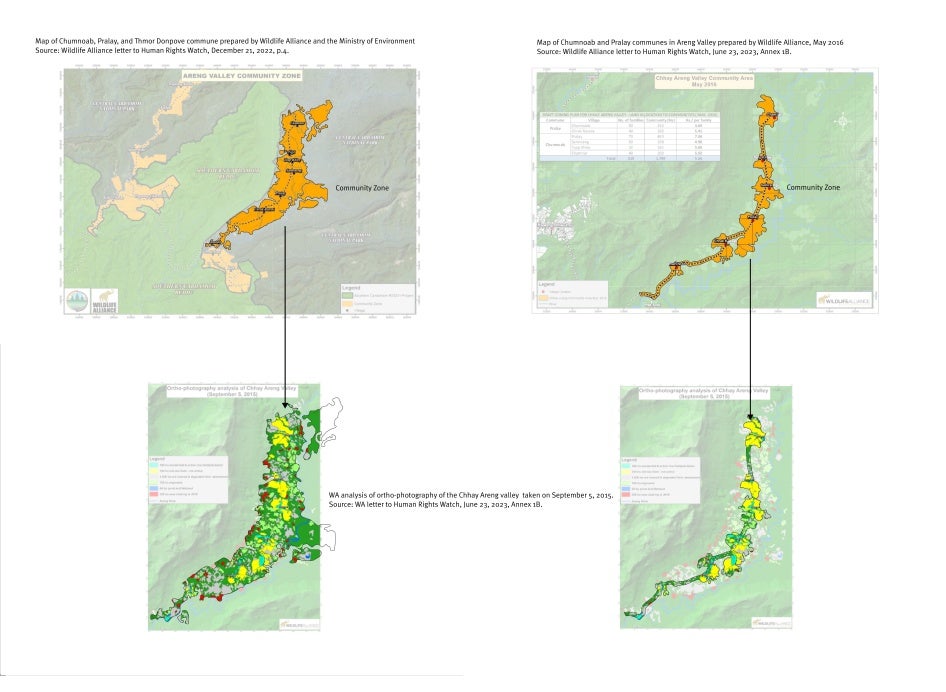

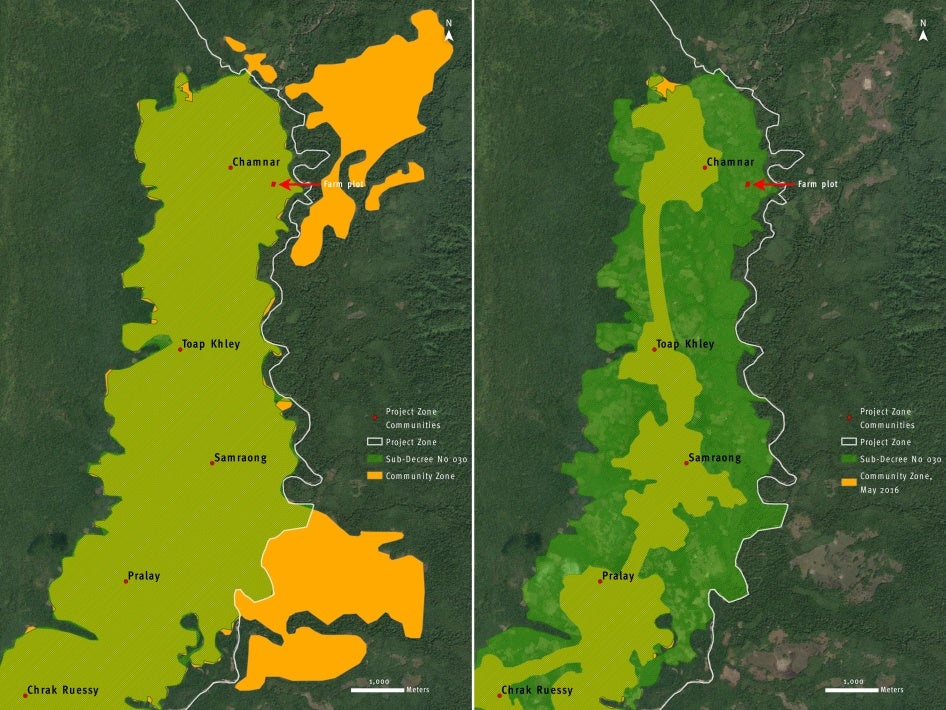

The DIL geospatial analysts reviewed satellite imagery to corroborate victims’ accounts of crops or homes that were destroyed and analyzed the different maps provided by Wildlife Alliance. The DIL geospatial analysts also reviewed historical topographic maps dating up to 1899 and contemporary satellite imagery to assess whether villages inside the REDD+ project preceded the creation of the project and the creation of protected areas. The data sources and methodology for all the geospatial analysis featured in this report is described in detail in Annex 2.

Human Rights Watch reviewed the REDD+ project’s official documentation, including the project description and the monitoring, verification and validation reports available on Verra’s registry, and the promotional material published on the websites of Wildlife Alliance, Wildlife Works Carbon (WWC), and Everland.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed relevant domestic legislation and policy documents of the Cambodian government on land rights, Indigenous rights, nature conservation, and REDD+.

Human Rights Watch additionally reviewed reports authored by local civil society organizations, independent experts, academics, and United Nations special procedures, treaty bodies, and regional human rights courts on land, Indigenous rights, and nature conservation.

Between September 2022 and February 2024, Human Rights Watch exchanged multiple letters and held meetings with the governmental and private entities involved in the design, funding, implementation, and accreditation of the project. This includes the Cambodian Ministry of Environment, Wildlife Alliance, Wildlife Works Carbon, SCS Global Services, Aster Global, and Verra. The dates and a brief description of those exchanges is available in Annex 1. All the correspondence that Human Rights Watch sent and the correspondence we received that was on-the-record and which we had permissions to reproduce is also available at a link provided in Annex 1.

I. The Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project (SCRP)

This section describes the different actors involved in the project, as well as its activities, scope, and the publicly available information on the revenue it has generated.

The Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project is a carbon offsetting project developed and implemented by Cambodia’s Ministry of Environment (MOE) and the nongovernmental organization Wildlife Alliance (WA). The for-profit private company Wildlife Works Carbon (WWC) invested in the project, helped fundraise for the project, provides technical advice for its implementation, and assists with the annual audits.

|

Carbon offsetting, in brief In principle, carbon offsetting is a mechanism that enables individuals, businesses, and governments to compensate for their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. One carbon credit represents one metric ton — or 1,000 kilograms — of carbon dioxide (CO2) that has been theoretically removed from, or prevented from being emitted into, the atmosphere.[2] A carbon credit is “retired” when the credit is used to offset an equivalent volume of the emissions it represents, also known as “carbon offsetting.” Forest carbon offsets, in brief To generate credits, some projects estimate the carbon stored in forests’ soils and vegetation. Based on this estimate, the project generates carbon credits for an equivalent volume of metric tons of carbon dioxide that would be released if the forest was razed. Several scientists have warned this accounting methodology often overestimates emissions reductions.[3] Others have expressed concerns about the permanence of reductions, given possible disturbances such as pests, fires, or changes in government policies.[4] |

Project Implementers

The MOE is the “project proponent.”[5] As a government institution in whose jurisdiction the project takes place, the MOE oversees all project activities and design. MOE rangers have authority to conduct law enforcement operations inside protected areas, including within the boundaries of the REDD+ project.[6]

WA is the “project implementer.”[7] WA is a nongovernmental organization that has operated in Cambodia since 2002 and conducts activities to combat deforestation and illegal wildlife trade in the Cardamom mountains region, provides training on agricultural intensification to smallholder farmers, and offers eco-tourism services.[8] WA was previously called WildAid and many Cambodians still recognize and refer to it by this name.[9] In its correspondence with Human Rights Watch, WA described itself as a “boots-on-the-ground, community-led conservationist organization.”[10]

WA also states that between 2002 and 2016, it “served as the technical partner for most of the zoning process” of the Cardamom rainforest, “supporting” the Forestry Administration and the Ministry of Environment.[11] They also stated that they provide “legal support” to Cambodian environmental law enforcement.[12] WA is responsible for implementing the “forest protection and community livelihood activit[ies],” according to the project’s description.[13]

WA manages the Cardamom Forest Protection Program (CFPP), a program that pairs WA advisors with MOE rangers and gendarmes from the Royal Gendarmerie Khmer to jointly conduct patrols, dismantle structures, destroy crops, conduct searches, seize timber and wildlife, arrest, interrogate, and transport individuals to detention centers, among other activities.[14] WA “has established 13 operating ranger stations covering the whole project area” of the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project, and WA “manages” stations.[15] WA also states it does capacity building for government rangers and equips them.[16] Overall, the REDD+ project employs more than 150 rangers.[17]

Wildlife Works Carbon is a private for-profit company that stated in 2021 it had developed 20 percent of REDD+ projects on the global market.[18] In correspondence with Human Rights Watch, Mike Korchinsky, the Wildlife Works Carbon CEO, said his organization was a “Technical Advisor and produced the technical documentation” for the project and “provided some training [to WA] and some financial support.”[19] In a videocall with Human Rights Watch, Mr. Korchinsky also said that Wildlife Works Carbon assists WA and the MOE in preparing the documentation required for continued accreditation under Verra’s standards and that it provided training to WA on how to conduct free, prior and informed consent consultations with communities included in the project, but Wildlife Works Carbon staff is not involved in the day-to-day implementation of the project.[20]

Everland, a for-profit company specialized in marketing carbon credits from REDD+ projects, was appointed by the Royal Cambodian Government to market the carbon credits generated by the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project.[21] (The company was established in 2017 by Wildlife Works Carbon, with Wildlife Works Carbon staff appointed to leadership positions in Everland.)[22] Everland says it represents the “world’s largest portfolio of high-impact REDD+ forest conservation projects, working on their behalf to market to businesses, on an exclusive basis.”[23]

Table 1. Entities involved in the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project

|

Entity |

Role in relation to the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project |

|

Royal Cambodian Government’s Ministry of Environment (MOE), the “project proponent” |

Environmental law enforcement Manages project revenue |

|

Wildlife Alliance, the “project implementer” |

Oversees the Cardamom Forest Protection Program (CFPP), an environmental law enforcement program with the MOE Implements community livelihood activities Manages project revenue |

|

Wildlife Works Carbon, the “technical advisor” |

Investor in the project Provided training on FPIC to WA Prepared the project design document Prepares the monitoring reports required to gain and maintain certifications |

|

Everland, the marketing firm |

Marketing Brokers sales of the project’s carbon credits |

Project Scope

According to the official project description, the REDD+ project began on January 1, 2015 and is due to end in December 2044.[24]

The REDD+ project is organized in two areas, an inner “Project Area” and an outer “Project Zone”:

- The inner “Project Area,” in which “project activities aim to demonstrate net climate benefits.”[25] This is mainly forested land that backs the issuance of carbon credits.

- The outer “Project Zone,” in which activities “related to provision of alternate livelihoods and community development, are implemented.”[26] The Project Zone includes 29 villages.[27] Several of these villages are completely or partially inside protected areas that are managed by the MOE and where the Cardamom Forest Protection Program overseen by WA conducts environmental law enforcement.

The project’s description acknowledges 3,841 families or 16,319 people in the 29 villages in the Project Zone.[28] The description notes that “100% of families are engaged in farming activities” in these communities and for a third “cultivation is the main occupation.”[29] (See Map 1.)

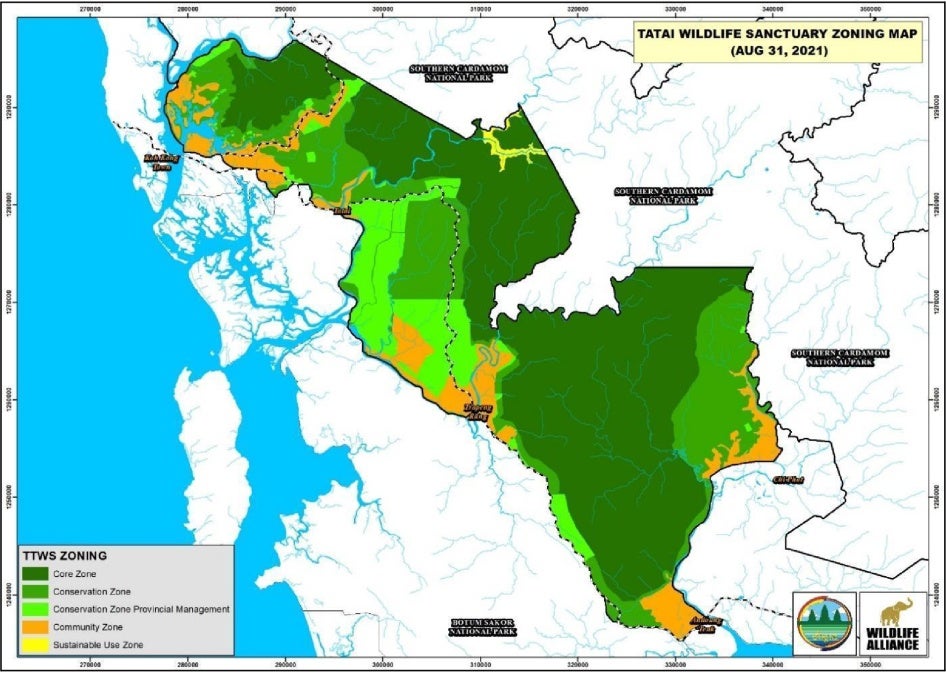

When considering the Project Zone and the Project Area together, the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project overlaps with all or parts of six protected areas under the purview of the MOE: parts of the Botum Sakor National Park, the Central Cardamom National Park, the Peam Krasop Wildlife Sanctuary, the Phnom Samkos Wildlife Sanctuary, the Southern Cardamom National Park, and the Tatai Wildlife Sanctuary (see Map 2).[30] The REDD+ project encompasses more than half a million hectares of land.[31]

Human Rights Watch found that at least 23 of the 29 villages included in the Project Zone are included, partially or entirely, within a protected area. Of the 23 villages, some appear to overlap with more than one protected area. The six villages that are neither partially nor totally included in a protected area but are within the boundaries of the Project Zone are Sovanna Baitong, Choam Sla, Teuk Laak, Kamlot, Krang Chek, and Bak Angrut. Human Rights Watch shared this assessment with WA in February 2023, but WA had not responded to the finding at the time of publication.[32]

Project Activities

WA and Wildlife Works Carbon worked to “attract investors” as of 2012.[33] In 2015, the MOE and Wildlife Alliance began “forest protection and community development activities.”[34]

According to the first audit of the project, between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2017, the project achieved the removal of nearly 12 million tons of CO2 equivalent.[35] This enabled the REDD+ project to start issuing carbon credits in 2018 based on activities it began conducting on January 1, 2015.[36]

WA wrote to Human Rights Watch that between June and July 2023, it “reached out to all the Commune Chiefs within the Project Zone,” and 11 of them “decided to provide a letter of support to the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project,” for which WA provided a template.[37]

(Commune chiefs are officials employed by the Royal Government of Cambodia, the project proponent.) Several of these letters described activities said to be carried out by the project in the commune chiefs’ constituencies.[38] Considering these letters alongside correspondence from WA and reports the project submitted to Verra, between 2015 and 2023, the project’s activities are said to have included:

- “Delineat[ing] boundaries of land used by the communities and their farmland,” leading up to the creation of the Southern Cardamom National Park in 2016.[39]

- Installing 1,203 demarcation posts between 2015 and 2021 to separate forest and community areas.[40]

- Intensifying “patrolling of the Project Area” to prevent deforestation.[41]

- Rescuing animals “from hunters’ snares,” removing snares, confiscating chainsaws, and seizing logs.[42]

- Establishing an eco-tourism project in Chhay Areng valley in 2016.[43]

- Providing training for “sustainable agricultural intensification” and “chicken and frog raising.”[44]

- Providing bursaries for youth to attend university.[45]

- Creating “Women’s Saving Groups.”[46]

- Building water wells, toilets, and laterite roads, and installing streetlights.[47]

- Building two schools and one health post.[48]

Human Rights Watch did not verify the project activities said to have delivered benefits to local communities, the quality of services being provided, and whether these services were provided in ways that are aligned with international human rights standards. During the research team’s visits to communities in 2022, staff members saw several water tanks that were built by the project.

The project’s description states that more than 3,800 families estimated to live in the Project Zone will “have improved livelihoods or income generated as a result of project activities,” and that the project expects to employ approximately 200 people.[49]

Project Revenue

In August 2021, the REDD+ project reported more than US$18 million in revenue from carbon credit sales.[50] The same report states “the project has spent $6 million dollars in project activities” since 2015.[51] Then, in November 2022, the carbon marketing firm Everland brokered a deal with multinational corporations that committed to buy 10 million tonnes of carbon credits from the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project.[52]

Human Rights Watch requested up-to-date information about the revenue generated by the project’s sale of carbon credits in 2022, as well as a breakdown of how the revenues have been used, but neither WA nor the MOE had responded to these queries at the time of publication.[53] The REDD+ Project does not have a benefit sharing agreement with any of the communities included in the project, but agreements over revenue distribution have been concluded between WA, the Cambodian national government, and the local government of Koh Kong province, according to WA’s website.[54]

In the page entitled “Open Letter to Stakeholders” of its website, WA disclosed partial information on revenue and expenses. (While the letter was first published in December 2023, an addendum on “Benefit Sharing” was subsequently added between January and February 2024, at an unspecified date.)[55] The website does not state the overall revenue or annual revenue of the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project, but states the project spent US$2,045,733 in 2023 in “community development activities,” and that the sum represented 36 percent of the “Annual Project Workplan” expenses, the remaining 64 percent being destined to forest protection activities.[56] The WA website does not state the percentage of overall revenue destined to the “Annual Project Workplan,” but it does state that the project must also pay Verra, marketing fees, and Cambodian government authorities.[57]

The project description notes that the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project “aims to utilize the revenue from emission reduction sales to provide a sustainable, consistent source of funding with which to maintain WA’s [Wildlife Alliance’s] protection activities and increase the number and size of project activities and their geographic influence.”[58] For her part, the WA CEO told news outlet Mongabay in October 2016 “the REDD+ Project is part of our business model for sustainable financing.”[59]

II. Chong Indigenous People in the SCRP

This section describes the Chong Indigenous communities that are present within the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project, the land use planning processes these communities have undergone, as well as WA’s participation in these processes.

The REDD+ project’s description acknowledges the Chong Indigenous people “have lived in the area for centuries.”[60] A subsequent project report states that the “[Chhay] Areng Valley is inhabited by eight forest communities (total population 461 families), the majority of which are ethnic Chong.”[61] Chong Indigenous people are also present in the three villages of O’Som commune, Veal Veng district, Pursat province, that are included in the Project Zone (see Table 2 below.)[62]

Table 2. Villages home to Chong Indigenous people in the

Project Zone of the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project

|

|

Village |

Commune, District and Province, |

Population |

|

1. |

Chrak Russey |

Chumnoab commune, Thmor Bang district, Koh Kong province |

175 |

|

2. |

Chumnoab |

213 |

|

|

3. |

Chhay Louk |

O’Som commune, Veal Veng district, Pursat province |

565 |

|

4. |

Kien Chungruk |

492 |

|

|

5. |

O’Som |

507 |

|

|

6. |

Chamnar |

Pralay commune, Thmor Bang district, Koh Kong province |

190 |

|

7. |

Pralay |

244 |

|

|

8. |

Samroang |

216 |

|

|

9. |

Toap Khley |

113 |

|

|

10. |

Koh |

Thmor Donpove commune, Thmor Bang district, Koh Kong province |

218 |

|

11. |

Prek Svay |

374 |

Sources: Wildlife Works Carbon, “Southern Cardamoms REDD+ Project,” March 8, 2018, pp. 21-22; Human Rights Watch interviews with Chong elders and community leaders between April and July 2022; Cambodian government’s 2018 submission to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination.

These communities have faced substantial barriers to formal recognition of their land rights. To date, none benefit from a communal land title that would recognize their communal farmland, burial sites, or spirit forests.

O’Som

The government-backed construction of the Stung Atay hydroelectric dam, between 2009 and 2013, flooded thousands of hectares of O’Som commune, including tree spirits worshipped by the Chong people and Chong farmland in the Voa Pen area.[63]

While the government handed out permits to log the dam reservoir prior to flooding, large-scale illegal logging, particularly of rosewood, extended beyond the authorized area.[64] A prominent Cambodian environmental activist who investigated the logging was shot and killed in 2012.[65] Elders interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Chhay Louk village said people returned to the Voa Pen area after logging operations had ceased, to try to reclaim what was left of their farmland.[66]

In 2013, individual plots of residential land and farmland were surveyed in O’Som commune, as part of the implementation of Order 01 BB issued by Prime Minister Hun Sen.[67] Based on the Order, the prime minister sent thousands of volunteers to survey land plots and issue receipts to owners.[68] Landowners then had to undertake additional administrative procedures to convert the receipt into a land title conferring ownership rights.

Crucially, this process did not require a survey of Indigenous communal land such as burial sites or spirit forests – instead, survey of Indigenous territories must be at the initiative and expense of residents, and the government must recognize the Indigenous status of the community as a precondition for surveying, as detailed in sub-decree no. 83.[69] The prime minister’s volunteers who surveyed O’Som commune therefore did not have a mandate to survey Voa Pen as communal property at the time they conducted this work.

According to WA, in 2017 WA worked with government authorities to redraw the boundaries of Chhay Louk village in O’Som commune, which conferred 409 additional hectares to the village.[70] In correspondence with WA, Human Rights Watch requested the minutes of the land use planning meetings held between WA and the government, to obtain documentation that could support WA’s statement.[71] WA said it did not have the minutes, though it did provide minutes for several other communes where it said it had been involved in the zoning.[72]

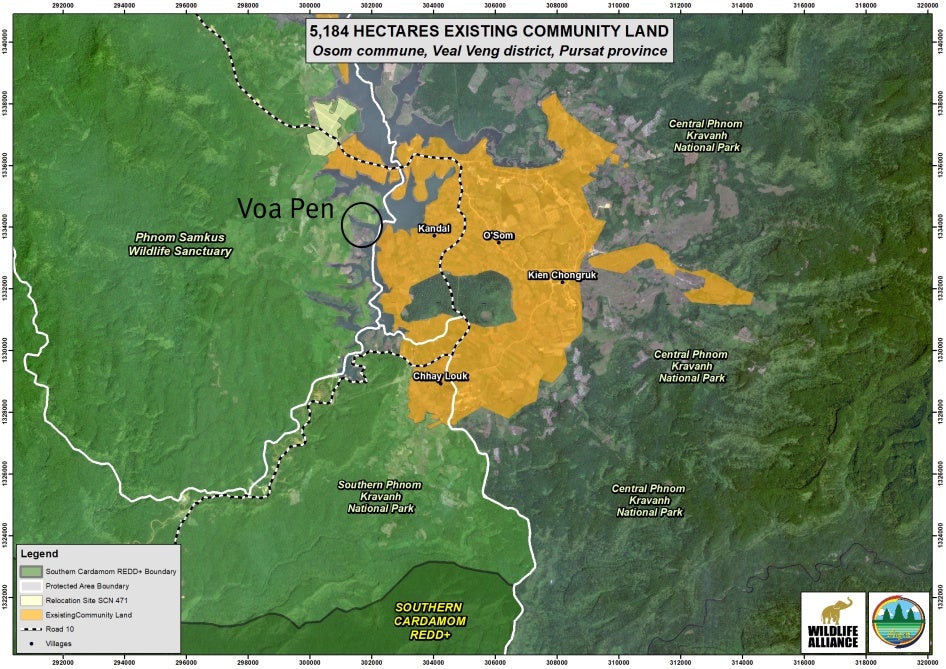

WA provided a map of O’Som commune that indicates the centers of Chhay Louk, Kien Chungruk, and O’Som villages, but not the outlines of individual villages (see Map 3 below).[73] This map shows that the commune stretches over three protected areas: the Phnom Samkos Wildlife Sanctuary, the Central Cardamom National Park and the Southern Cardamom National Park (these are also known as Central Phnom Kravanh National Park and Southern Phnom Kravanh National Park, the name in Khmer of the Cardamom Mountains). Each protected area is required to undergo its own zoning process under the 2008 Protected Areas Law, which defines inner boundaries marking which parts of the park allow for human settlements, farming, and gathering of forest products, for example.[74] This process has not yet been completed for any of these three protected areas, keeping residents in limbo about their land rights.[75]

Chhay Areng Valley

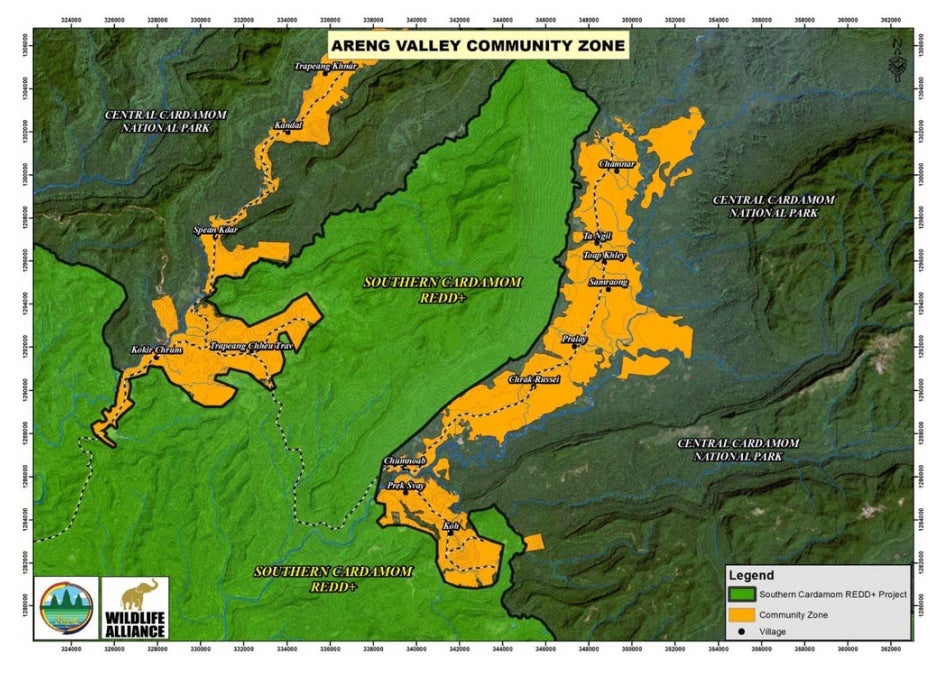

In the Chhay Areng Valley, the situation of the Chong communities has also been fraught with difficulties. There are a total of eight villages across three communes –Chumnoab, Pralay, and Thmor Donpove – in the valley.[76]

The communities in Chhay Areng valley were successful in stopping the construction of the Steung Areng dam. The dam would have flooded their villages, farmland, burial sites, and spirit forests, and displaced an estimated 1,500 people.[77] Chong Indigenous leaders and environmental defenders from the group Mother Nature Cambodia maintained a roadblock between May and September 2014 that prevented construction from moving forward.[78]

However, this victory for the community came at a cost. In October 2015, a Chong Indigenous leader was jailed on spurious charges for six months.[79] The Cambodian Center for Human Rights’ analysis of the evidence supporting the case concluded the charges lacked any legal basis and the defenders’ conviction and imprisonment was likely retaliation for his role in organizing Chong people to resist the dam.[80]

The threat of the dam led Chong people to seek support from the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), which in December 2015 began assisting five villages in Chhay Areng valley to gain recognition of their Indigenous status by the government.[81] Petitioning the government for five villages to be recognized as Indigenous Chong, which is only the first step towards a communal land title, cost approximately US$40,000.[82] OHCHR footed the bill, which supported the communities, but the exorbitant cost underscores the financial barriers that Indigenous people face to exercise their rights.[83]

In 2016, the Chong also created Community Committees for each of the eight villages in the valley. Committee members and leaders were elected by village residents through suffrage. The committees, each with five to seven elected members, make decisions on agriculture, tourism, development, as well as documentation of Chong culture and tradition.[84]

In May 2016, the entire Chhay Areng valley and all its eight Chong villages were incorporated into the Southern Cardamom National Park, following years of advocacy by WA towards the creation of the park.[85]

In 2017, the government recognized the Indigenous identity of three of the villages that requested it in 2016 (Chrak Ruessey, Koh, and Prek Svay).[86] At the time of publication two villages had not yet received a response (Chumnoab and Pralay).[87] Pralay village submitted a new request in May 2023.[88]

Thmor Donpove Commune

In 2013, as part of the implementation of the Prime Minister’s Order 01 BB, volunteers surveyed individual plots of residential land and farmland in Thmor Donpove commune.[89] Surveys conducted following Order 01 BB did not map communal Indigenous land such as burial sites, spirit forests, or other sites of spiritual significance to the Chong.[90]

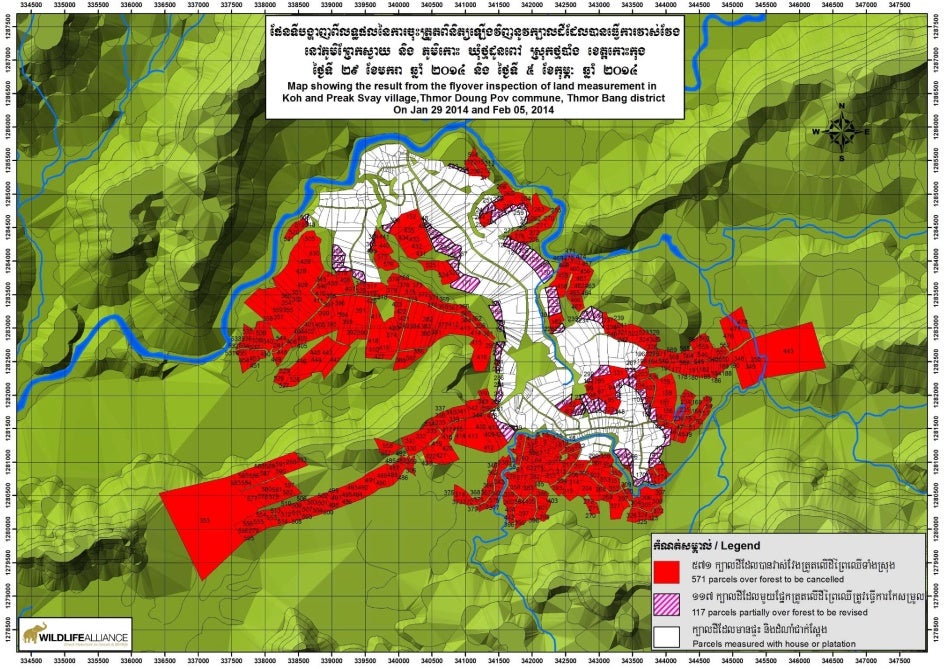

That year, WA contested 1,851 hectares that had been surveyed to become part of the commune. In the map below provided by WA (Map 4), these are marked in red or striped.[91] WA argued that the plots were irregularly surveyed over forested land.[92] An investigation into WA’s complaint by the Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning, and Construction found that 35 percent of the land that WA contested was farmland being occupied and an additional 5 percent was a mix of field and forest, with the remaining 60 percent being forestland.[93]

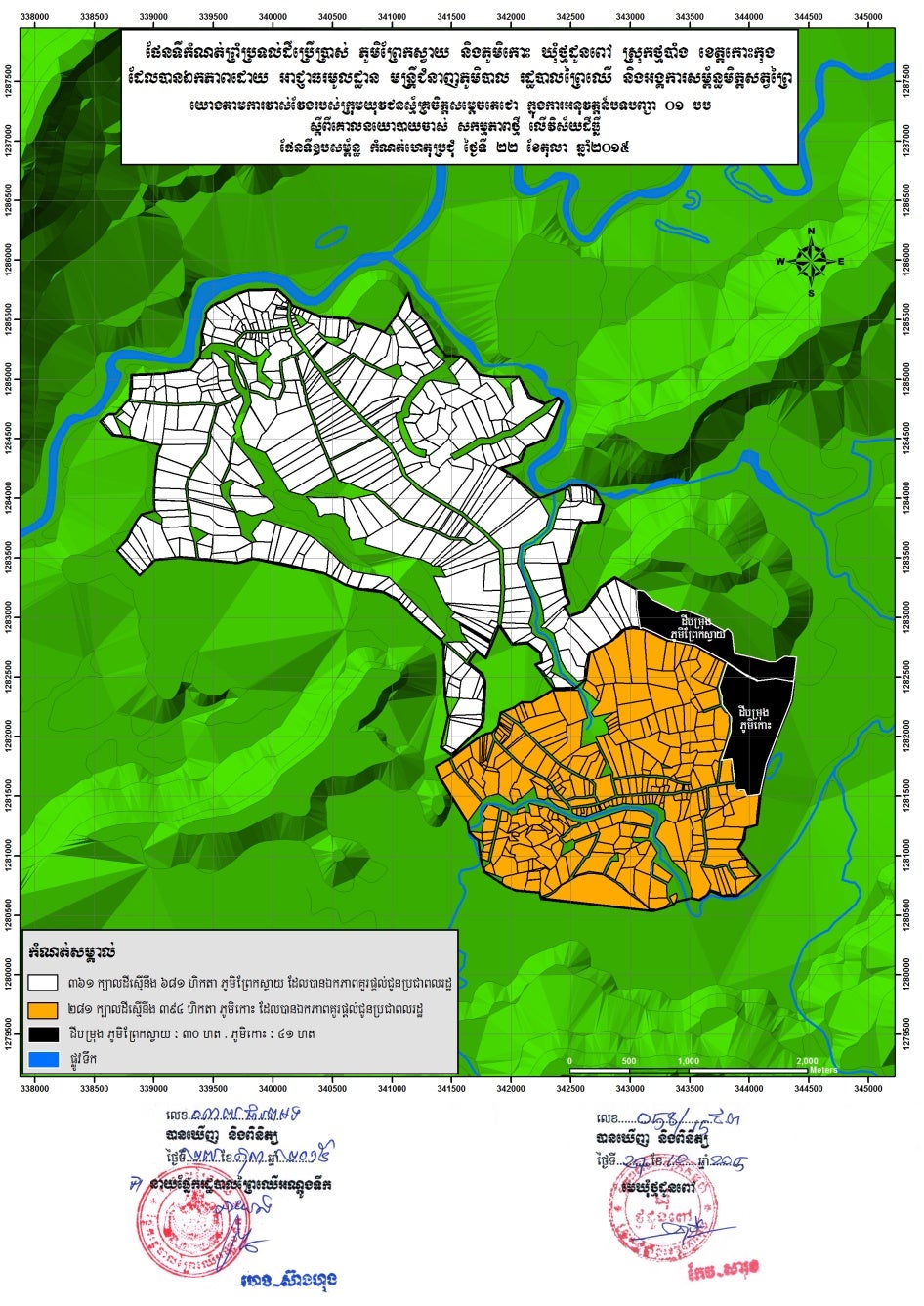

It was not until October 2015 that government officials and WA agreed on a map of the commune, according to the minutes of the meeting shared by WA.[94] The minutes of the meeting do not state how much of the contested land ultimately made it into the map.[95] Nonetheless, this second map (see Map 5 below) does show that most of the contested plots that were previously marked in red or striped were ultimately eliminated from the Thmor Donpove commune final map following WA’s intervention.

Despite this lengthy process, in April 2022 a government official with knowledge of the matter told Human Rights Watch that no one in the Thmor Donpove commune had received land titles.[96]

In July 2017, the two villages in Thmor Donpove commune gained recognition from the government of their Indigenous Chong identity, a process initiated by community members in December 2015 with support from OHCHR.[97]

Chumnoab and Pralay Communes

In Chumnoab and Pralay communes, neither individual plots nor communal land have been surveyed by the government. A Chong Indigenous leader from Chumnoab commune told Human Rights Watch he believed the government’s plan to build the Steung Areng dam had prevented land titling.[98] (In correspondence to Human Rights Watch, WA also wrote that “land registration of Chhay Areng’s six villages could not proceed because the villages were going to be flooded for the dam’s reservoir.)[99]

Between June 2015 and March 2016, WA conducted a “livelihood assessment” of the villages, took aerial photographs of the valley, calculated how much farmland they believed should be assigned to families in each village, and proposed a draft zoning map to the provincial governor of Koh Kong, according to WA.[100] Between March and April 2016, WA then took steps to “ground truth” the proposed boundaries, with, according to WA officials, participation from local officials and residents.[101]

WA presented the zoning map they prepared to the Provincial State Land Management Committee of Koh Kong in May 2016, and, according to WA, this was the “final community area map.”[102] However, in their correspondence with Human Rights Watch, WA shared two different maps of Chumnoab and Pralay communes whose boundaries did not match.[103]

In July 2017, Chrak Russey village in Chumnoab commune gained recognition from the government of their Indigenous Chong identity, a process initiated by community members in December 2015 with support from OHCHR.[104] In May 2023, Pralay village in Pralay commune submitted a request for official recognition of their indigenous identity, and the Pralay commune chief has encouraged other villages to do the same, according to WA.[105]

III. Verra Certifications Granted to the SCRP

The Ministry of Environment (MOE) and Wildlife Alliance (WA) have sought to have the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project certified as complying with several standards managed by Verra, a private US-based nonprofit corporation. Verra was founded in 2007 with the objective of providing “greater quality assurance in voluntary carbon markets.”[106] Verra is the largest organization in the voluntary carbon market’s certification industry.[107]

Verra administers numerous standards under which they guarantee the environmental and social integrity of carbon offsetting projects listed in their registry. Verra has also a memorandum of understanding with the Royal Cambodian Government to “support capacity building and discussions around technical matters, including registry development and linkages.”[108]

The Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project has subscribed to three of Verra’s certification programs:

• The Verified Carbon Standard (VCS), version 3.4, which certifies the environmental integrity of the carbon credits issued.[109] Where Verra certifies projects using this standard, Verra issues Verified Carbon Units (VCUs), which are tradeable emissions reductions.[110] Only this accreditation is required to be listed on Verra’s registry, while others are optional.

• The Climate, Community and Biodiversity Standards (CCB), version 3.0, an optional standard that projects can subscribe to, certifies that projects uphold the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities in line with the Cancun Safeguards.[111]

• The Sustainable Development Verified Impact Standard (SD VISta), another optional standard that certifies that projects benefit local communities in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).[112]

Projects that also obtain Verra’s CCB or SD Vista certifications can apply these labels to their VCUs and sell them at a higher price compared with VCUs that do not have these labels.[113] Verra wrote to Human Rights Watch that a “project may retroactively apply CCBS or SD VISta labels to VCUs, provided that verification from the respective program are approved for the VCUs in question.”[114]

By June 2023, the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project had issued a total of 27,627,237 VCUs, of which 5,321,735 have been retired.[115] (A credit is retired once it has been claimed as an offset by the buyer, after which the credit can no longer be traded in the market.) All the VCUs issued by the project bear a CCB label.[116] Of these, 11,991,197 VCUs issued by the project also bore SD VISta labels.[117]

Verra is registered as a nonprofit corporation under US law and earns revenues by certifying projects, by listing projects in its registry, and for issuing credits for projects.[118]

To obtain Verra’s certifications, project developers produce periodic reports (“monitoring” reports) describing the design and implementation of the project.[119] Developers must contract auditing firms authorized by Verra to verify the information presented in their reports.[120] The auditing firms then issue their own reports (“validation” and “verification” reports) assessing whether the information in the project implementers’ reports is correct.[121]

Auditing firms may open “findings” if they believe something about the project does not conform with the standard. Project implementers must address these findings through written comments as well as conversations with auditors that are not transcribed in the audits. Auditors will close the finding if they deem it has been adequately addressed.

The auditing firms are paid by the project developers to conduct their work.

All reports are made available to Verra, which makes final decisions to grant certifications, or not, as well as whether to issue credits. The overall administration of these certification programs rests with Verra.[122]

In Human Rights Watch’s view, Verra’s operating model has fundamental conflicts of interest since an independent evaluation process is actually conducted by financially self-interested parties from beginning to end in the regulatory vacuum of the voluntary carbon market.

When Human Rights Watch began the research for this report, objections to decisions taken by Verra on “an aspect of how it operates a program(s) managed by Verra, or a claim that relevant program rules have had an unfair, inadvertent or unintentional adverse effect” could be submitted through its complaints and appeals procedure.[123] Verra would assess the complaint internally and provide a written response to the complainant.[124] If the matter was not resolved to the satisfaction of the complainant, the latter may appeal to Verra’s Board, whose decision is “final and binding.”[125] The cost of the entire process was borne by the complainant if the decision was not favorable to them.[126]

In June 2023, Verra wrote to Human Rights Watch that they would waive expense reimbursement requirements “on a case-by-case basis” and that they were “updating” their Complaints and Appeals Policy to explicitly waive reimbursement requirements.[127] In December 2023, Verra published a new Complaints and Appeals Policy that indeed no longer requires complainants to pay in order to have their allegations investigated, and provides a timeline for the resolution of complaints, among other improvements over its previous procedure.[128]

Verra also wrote to Human Rights Watch that, in the event a project is found to be in breach of the standard that Verra manages, and caused harm as a result, Verra would:

investigate concerns raised by stakeholders, project proponents, validation/verification bodies, and/or Verra itself, and will initiate a new review of the project where circumstances warrant. If we find that, as a result of the fraudulent conduct, negligence, intentional act, recklessness, misrepresentation, or mistake of the project proponent, there has been a material erroneous issuance of VCUs in respect of the project, the project proponent may be responsible for compensating for such issuance. [Section 6 of the VCS Registration and Issuance Process] The SD VISta Program includes a similar review procedure. [Section 3.11 of the SD VISta Program Guide, v1.0] Under the CCBS Program, Verra may suspend projects either at our discretion or in the event that we receive information indicating a project is failing to meet the rules and requirements of the program. A suspended project must undergo a full reassessment process in order to have its validated or verified status reinstated. [Section 4.7.3 and 4.7.4, CCB Program Rules, v3.1] Verra may also suspend or terminate a user’s account in the Verra Registry, including where we reasonably suspect that the user has engaged in fraudulent, unethical, or illegal activity.[129]

While Verra’s response provided some clarity into how it would assess the project proponent’s behavior, Verra did not clarify how it would independently investigate complaints where Verra staff could be implicated in “fraudulent conduct, negligence, intentional act, recklessness, misrepresentation, or mistake.”[130]

On May 30, 2023, Human Rights Watch shared its preliminary findings with Verra about the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project.[131] On June 20, Verra wrote to Human Rights Watch that it had “decided to investigate the concerns that [Human Rights Watch] raised” and was initiating “a new review of the project.”[132] Verra also stated it was “effective immediately… suspending any further credit or label issuance to the [Southern Cardamom REDD+] project under the VCS, CCBS, and the SD VISta Programs.”[133] Verra completed its review of the project on August 21, 2023, issued findings and tasked the auditing firm SCS Global Services to provide written responses to the findings.[134] Verra did “not contact any project stakeholders or community members directly” for its review.[135] Verra had not communicated its findings to Human Rights Watch at the time of publication.

While Verra’s review was underway, on August 2, 2023, WA staff approached a woman who had previously given an account to Human Rights Watch (WA states this was part of their process to “verify the veracity” of the claims made by Human Rights Watch).[136] The woman had told Human Rights Watch that WA and MOE rangers had arrested her while she was on her farmland.[137] Human Rights Watch did not share her name or other identifiable details with WA, as a measure to prevent and mitigate reprisals against her or her family.

When WA staff approached her, they were accompanied by two Cambodian government officials, and they had the witness sign a print statement during the meeting.[138] The print statement, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, incriminated the witness, and could be used in court during a prosecution against her.[139] Further, these actions identified the witness to Cambodian government officials as someone who had provided testimony to Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch shared the information it had available about the incident with Verra on August 18, and requested that Verra disclose how it would assess this conduct as part of its review, and more generally how Verra ensured the protection of individuals during its project reviews.[140] On September 25, Verra wrote to Human Rights Watch that they “do not contact any project stakeholders or community members directly” during project reviews, and that their “communications with the project proponent are limited.”[141] On October 12, Verra added it would not “provide any further comments on the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project until [their] review is complete.”[142]

In August 2023, Verra adopted a human rights policy. It states that where Verra has “concerns” that any of its “business partners are linked to human rights violations” or that Verra’s work “will be directly or indirectly linked to human rights violations by a business partner,” Verra will:

(1) use our Policy as a basis to communicate our expectations and work with them to mitigate these impacts, as appropriate, (2) only proceed with the relationship if we are comfortable that our work will not contribute to human rights violations, and/or (3) always be prepared to walk away from engagements where our integrity or commitment to respect for human rights could be called into question if we continued.[143]

At the time of publication, Verra had not shared the outcome of its review of the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project with Human Rights Watch.

IV. Human Rights Violations in the SCRP

Impacts on Indigenous Peoples’ Right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent

Requirement to Obtain Consent

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples calls upon states to “consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them.”[144]

Verra’s CCB standard requires that:

The project recognizes respects and supports rights to lands, territories and resources, including the statutory and customary rights of Indigenous Peoples and others within Communities and Other Stakeholders. The Free, Prior and Informed Consent … of relevant property rights holders has been obtained at every stage of the project. […] Consent means that there is the option of withholding consent and that the parties have reasonably understood it [emphasis in the original].[145]

In 2018, the first audit of the project – conducted by SCS Global Services – established that all 29 villages in the Project Zone were “relevant property holders” under the definition of the CCB standard and that “the CCB requirement that ‘free prior and informed’ consent’ … be ‘obtained at every stage of the project’ holds for the SCRP.”[146]

In this regard, SCS Global Services interpretation of Verra’s CCB standard aligns with international standards on the right to FPIC of Indigenous peoples. Indeed, SCS Global Services determined that, to move forward with the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project, WA and the MOE were required to seek and obtain the consent of Indigenous peoples impacted by the project.[147]

However, during the audit conducted by SCS Global Services and in subsequent correspondence with Human Rights Watch, WA maintained that they do not consider themselves bound to obtain the consent of Indigenous communities to implement the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project.

The SCS Global Services’ 2018 audit raised concerns about the lack of support for the project in one of the communities included in the Project Zone.[148] The audit report reproduces verbatim the REDD+ project’s “personnel” response to the auditor:[149]

We assume that as the communities [in the Project Zone] have no land rights to or within the Project Area, their participation in the REDD+ Project is entirely voluntary, and in no way is their participation obligatory, either for the community(ies) or the project developers. We therefore assume that a formal consent is not required from communities in the Project Zone for the validation of the project, as they have no land rights to or within the Project Area.[150]

SCS Global Services reiterated to the MOE and WA their determination that all 29 villages in the Project Zone were indeed “relevant property holders” under the definition of the CCB standard and insisted that “the CCB requirement that ‘free prior and informed’ consent’ … be ‘obtained at every stage of the project’ holds for the SCRP.”[151]

Following this exchange, the project “personnel” contended that the FPIC criteria under the CCB standard was unclear and that, in any event, few projects could achieve unequivocal support.[152] They pointed out that WA had involved higher-level representatives of government in more recent meetings and that, by June 2018, they had secured an approval rate of at least half or more participants who attended meetings in villages where the approval rate had previously been lower.[153]

In short, while maintaining that they were not required to gain consent, the project implementers argued to SCS Global Services that they had nonetheless tried to obtain it.

This position was reiterated by WA in in a letter addressed to Human Rights Watch on December 21, 2022. WA stated that “consent is not required as part of the Free Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) process” under Verra’s VCS and CCB standard.[154]

At the time of the audit conducted by SCS Global Services, the project personnel knew that Indigenous people resided in the Project Zone, and they had acknowledged this fact in the project description.[155] Their insistence that they are not obliged to obtain the consent of Indigenous peoples affected by the project contradicts international human rights law, the project’s verification standard, and even the auditors’ own initial finding.[156]

Timing of Meetings

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples posits that States “shall” seek the free and informed consent of Indigenous peoples “prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources.”[157]

According to Verra’s CCB standard, consent by affected Indigenous peoples must be given “sufficiently in advance of any authorization or commencement of activities and respecting the time requirements of [local communities] decision-making processes.”[158] The manual recommended by Verra for the implementation of the CCB standard also states that consent should be measured on at least three levels:

Consent to discuss the idea for a REDD+ project that will affect community forests,

Consent to participate in developing a detailed plan for a project, and

Consent to the implementation of the project.[159]

Project documents state that the project began on January 1, 2015.[160] In correspondence with Human Rights Watch, WA stated that they “conducted the first FPIC community engagement meetings in 2017,” and the project description of the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project submitted to Verra specifies the first meetings were held in August 2017.[161]

When asked about the 31-month time lag between the project start date and the start date of the process of seeking consent, WA provided four different responses, described below.

First, in December 2022, WA stated it held “participatory land use-planning meetings” between 2003 and 2016 to define the boundaries of villages included in the Project Zone, suggesting these meetings were part of the consultation process to obtain the free, prior, and informed consent of communities impacted by the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project.[162] WA reiterated this reasoning in its June 2023 letter to Human Rights Watch.[163]

However, Human Rights Watch’s reviewed all the minutes of “participatory land use-planning meetings,” provided by WA, and did not find references to the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project.[164] According to the minutes of these meetings, the participants were Cambodian government officials and WA staff; they discussed the surveys conducted by volunteers implementing the Cambodian Prime Minister’s Order 01 BB, a nation-wide land surveying and titling campaign that began in 2012.[165] Those minutes reflect that WA staff argued that thousands of land plots were irregularly surveyed during the titling campaign initiated by the Prime Minister, and that WA advocated that these land plots should not be considered eligible for titling.[166]

Second, in August 2023, WA also responded that the official start date recorded in the project description (January 1, 2015) submitted to Verra was a technical backdating “to capture activity that had been carried out by Wildlife Alliance,” but that the project was not in existence before the first meetings were held in August 2017.[167]

However, in the same letter, WA stated that in February 2017, “Wildlife Alliance and the RGC signed contracts allowing the creation of the SCRP.”[168] At the same time, the validation report issued by auditing firm SCS Global Services states that the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project reduced or avoided nearly 12 million tonnes of emissions “as a result of” the project activities conducted between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2017, thus stating that project activities had commenced in January 2015.[169]

Additionally, WA’s correspondence described project activities that they and the Cambodian government conducted between January 1, 2015 and December 31, 2017. WA stated that between October 2015 and May 2016, it took steps with the Cambodian government to map the Indigenous Chong villages in Chhay Areng valley, and that these boundaries were “integrated by the Provincial State Land Management Committee into the zonation of the Southern Cardamom National Park,” which was created in May 2016.[170] (In June 2016, the WA CEO also told news outlet Mongabay that WA had worked with community and government to “re-measure land allocated to communities” in order to finalize the creation of the national park.[171]) The Southern Cardamom National Park enclosed 12 villages, of which 8 are home to Indigenous Chong people. WA wrote to Human Rights Watch that the creation of the national park was a “critical” moment for the REDD+ project.[172] The national park now forms most of the Project Area, backing the issuance of carbon credits for the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project.

Third, in August 2023, WA also responded that international law “does not clearly identify a single, precise point in time when FPIC must begin.”[173]

However, while international standards on the right to FPIC are formulated in a generic language to cover the vast range of situations to which they are applicable, both international human rights standards and Verra’s CCB standard are consistent in requiring that consent should be sought “prior” to the approval or implementation of the activity that impacts Indigenous peoples.[174]

Fourth, in November 2023, WA wrote that “you, HRW, claim that engagement meetings began taking place in August 2017, which is factually incorrect,” and listed activities conducted by WA in the Chhay Areng valley as of 2015, including surveying Indigenous land.[175]

However, it is WA’s letters to Human Rights Watch and the REDD+ project’s official documents, that state that the FPIC meetings began in August 2017, not Human

Rights Watch.[176]

Despite consultations taking place 31 months after the start of the project and after the MOE and WA had taken meaningful decisions about the project’s design and implementation, in its validation report the auditing firm SCS Global Services concluded that the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project met the requirement under the CCB standard that consent by affected Indigenous peoples must be given “sufficiently in advance of any authorization or commencement of activities.”[177]

When asked about this discrepancy, SCS Global Services responded that they had audited the project in relation to Verra’s VCS and the CCB standard, that they verified that the start date of the project was January 1, 2015, that they verified that FPIC meetings “began in August 2017, which is not prior to the start of the project” but that this was “in conformance” with the VCS and CCB standard.[178]

In Human Rights Watch’s view, SCS Global Services’ interpretation is neither consistent with the text of the CCB standard, nor with the requirements of international human rights standards on the right to FPIC.

When contacted by Human Rights Watch, Verra confirmed that they had validated the Southern Cardamom REDD+ Project under the CCB standard on November 11, 2018.[179] Verra stated it would investigate the concerns raised by Human Rights Watch and initiate a new review of the project.[180] At the time of publication, the review was ongoing.

Based on the information received from all the parties and the project’s documentation, Human Rights Watch concluded that the MOE and WA failed to uphold the right of Indigenous peoples to FPIC by making a series of decisions about the project’s approval, design, and implementation prior to commencing the consultation and these decisions had adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples’ rights and livelihoods.

Content of Engagement Meetings

Regarding the information that should be provided at consultations, the UN Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples recommends that:

The substantive content of the information [provided during consultation] should include the nature, size, pace, reversibility and scope of any proposed project or activity […]; the reasons for the project; the areas to be affected; social, environmental and cultural impact assessments; the kind of compensation or benefit-sharing schemes involved; and all the potential harm and impacts that could result from the proposed activity.[181]

Verra’s CCB standard requires that “[t]imely and adequate information [should be] accessible in a language and manner understood by the Communities and Other Stakeholders.”[182] The information provided should cover “the nature, size, pace, reversibility and scope of any proposed project or activity,” “the locality of the areas that will be affected,” and “a preliminary assessment of the likely economic, social, cultural and environmental impact, including potential risks and fair and equitable benefit sharing,” among others.[183]