(Beirut) – Qatari authorities should adopt and enforce adequate restrictions on outdoor work to protect the lives of migrant construction workers who are at risk from working in the country’s intense heat and humidity, Human Rights Watch said today.

Current heat protection regulations for the great majority of workers in Qatar only prohibit outdoor work from 11:30 a.m. to 3 p.m. during the period June 15 to August 31. But climate data shows that weather conditions in Qatar outside those hours and dates frequently reach levels that can result in potentially fatal heat-related illnesses in the absence of appropriate rest. International experts recommend work limitations based on actual weather conditions and the use of the authoritative Wet Bulb Global Temperature heat stress index to calculate appropriate work to rest ratios, not on predefined dates and times.

Authorities also should investigate the causes of migrant worker deaths, regularly make public data on such deaths, and use the information to devise appropriate public health policies, Human Rights Watch said. In 2013, health authorities reported 520 such deaths of workers from Bangladesh, India, and Nepal in 2012, of whom 385, or 74 percent, died from unexplained causes. Qatari public health officials have not responded to requests for information about the overall number and causes of deaths of migrant workers since 2012.

“Enforcing appropriate restrictions on outdoor work and regularly investigating and publicizing information about worker deaths is essential to protect the health and lives of construction workers in Qatar,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “Limiting work hours to safe temperatures – not set by a clock or calendar – is well within the capacity of the Qatari government and will help protect hundreds of thousands of workers.”

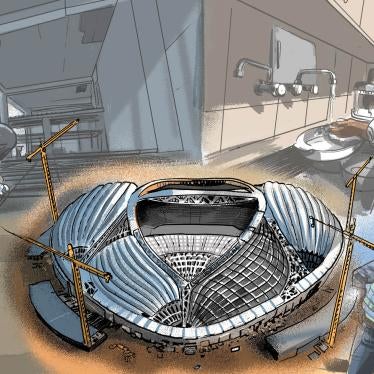

Qatar has a migrant labor force of nearly 2 million, who comprise approximately 95 percent of its total labor force. Approximately 40 percent, or 800,000, of these workers are employed in the construction sector. Since December 2010, when Qatar won its bid to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup, the country has embarked on a massive building spree – restoring or building eight stadiums, hotels, transportation, and other infrastructure. Qatari authorities have said they are spending US$500 million per week on World Cup-related infrastructure projects.

In contrast to the rudimentary and inadequate heat laws for workers, Qatar’s 2022 FIFA World Cup organizers, the quasi-governmental Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy, in 2016 mandated work-to-rest ratios, commensurate with the risk posed by heat and humidity, for the workers building stadiums for the tournament.

However, these creditable requirements only apply to just over 12,000 workers who are building stadiums for the World Cup – about 1.5 percent of Qatar’s construction workforce – and take no account of the effect of sunlight, which significantly increases the risk of heat stress. Supreme Committee officials told Human Rights Watch that they expect the number of workers on their projects to peak at around 35,000 by late 2018 or early 2019.

“If Qatar’s World Cup organizers can mandate a climate-based work ban, then the Qatar government can follow its lead as a step towards providing better protection from heat for all workers,” Whitson said.

The lack of transparency on migrant worker deaths has made it difficult to assess the extent to which extreme weather conditions are harming those working outdoors. A 2014 report that the Qatari government commissioned from the international law firm DLA Piper noted that the number of worker deaths in Qatar attributed to cardiac arrest, a general term that does not specify cause of death, was “seemingly high.” The authorities have failed to implement two key recommendations from that report. First, Qatar has not reformed its laws to allow autopsies or post-mortem examinations in cases of “unexpected or sudden deaths,” which the report says “should be performed” in any case of sudden or unexpected death; the law provides that autopsies may be performed to determine if the death was the result of illness, but should be expanded to explicitly authorize autopsies in cases of sudden or unexpected deaths. In addition, Qatari authorities have not commissioned an independent study into the seemingly high number of deaths vaguely attributed to cardiac arrest.

Moreover, Qatar has not made public meaningful data on migrant worker deaths for four years that would allow an assessment of the extent to which heat stress is a factor. Qatari authorities responded to an inquiry from Human Rights Watch about deaths of migrant workers at workplaces with figures indicating 35 workplace deaths, mostly from falls, presumably at construction sites, for 2016. The government has not provided the total number of deaths of migrant workers in 2016, but partial information from sending-country embassies indicates that the yearly migrant worker death toll has been in the hundreds.

International human rights law obliges all states to take necessary and reasonable steps to protect individuals’ right to life. This includes putting in place and enforcing legislation that provides effective protection to workers engaged in activities that pose a serious risk to life. States also have an obligation to collect information, undertake studies and compile reports about the risks associated with inherently dangerous types of work.

The Supreme Committee has provided information on worker deaths for projects under its purview. Out of a total of ten worker deaths on World Cup projects between October 2015 and July 2017, the Supreme Committee classified eight deaths as “non-work-related.” It has listed seven of these deaths as resulting from “cardiac arrest” and “acute respiratory failure,” terms that obscure the underlying cause of deaths and make it impossible to determine whether they may be related to working conditions, such as heat stress.

“As Qatar scales up its FIFA World Cup construction projects, authorities need to scale up transparency about worker deaths that could be heat related, and take urgent steps to end risks to workers from heat,” Whitson said.

Qatari authorities should immediately replace the work ban limited to midday summer working hours with a legally binding requirement based on actual weather conditions consistent with international best practice standards. This should include rest-to-work ratios commensurate with the risk from heat and humidity exposure, access to shade, plentiful hydration, and the prohibition of work at all times of unacceptable heat risk. The authorities should engage heat-stress specialists in drafting legislation, which should include meaningful sanctions for non-compliance.

Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates – the other five members of the Gulf Cooperation Council – all operate similar summer working hours’ bans that are not linked to actual weather conditions, and migrant workers in these countries are also vulnerable to similarly extreme temperatures.

“Qatar sought the spotlight by bidding for the 2022 World Cup, brought in hundreds of thousands of migrant workers to build roads, stadiums, and hotels, and then shelved key recommendations from their own consultants to investigate migrant worker deaths,” said Whitson. “FIFA and national football associations should make clear they expect life-saving changes to law and practice that could set a Gulf-wide example of how to save construction worker lives now – and in the future.”

Risks to Workers from Heat and Humidity

Qatari authorities’ strategy to mitigate heat-related risks to outdoor workers is limited to the 2007 decree prohibiting outdoor work between 11:30 a.m. and 3 p.m. during the period from June 15 to August 31, a rudimentary summer working hours ban. This system is demonstrably inadequate to address the very real heat-related risks that outdoor workers face due to very high temperatures in Qatar outside these hours and times of year.

In 2005, a paper written by three doctors employed at the intensive care unit of Hamad Hospital and published in the Qatar Medical Journal warned of the dangers of heat stroke to “unacclimatized outdoor workers” and outlined recommendations to minimize the risks to worker health. It recommended that “national public health authorities need to update the current heat emergency response plans with emphasis on their ability to predict mortality and morbidity associated with specific climatologic factors and their public health effect.” Qatari authorities did not respond to questions about whether they have undertaken or funded any subsequent public health study into the health and safety risks associated with living and working outdoors in Qatar’s extremely hot and humid environment, and Human Rights Watch is unaware of any such study.

Temperature readings do not, in isolation, accurately reflect the risk to workers from heat stress. Labor institutions in other countries and the global standards-setting institution International Organization for Standardization (ISO) use heat stress indices, such as the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT), which measures the combined effect of temperature, humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation on humans. When the body generates heat faster than it can lose it, the core body temperature rises. An increase in core temperature beyond 39 degrees Centigrade creates health risks. ISO sets guidelines on exposure to help ensure core body temperature does not exceed 38 degrees Centigrade.

ISO Standard 7243 uses WBGT as the heat stress index to specify recommended rest/work cycles at different physical work intensities: a WBGT of 29.3 means the ratio of work vs. rest should be 45 minutes to 15 minutes for an acclimatized worker doing moderately exerting work; when the WBGT reaches 30.6, the work-rest ratio should be 30 to 30; when the WBGT reaches 31.8, the ratio should be 15 to 45; and if the WBGT goes above 38, no work can safely be performed. The threshold levels are lower for workers doing strenuous work.

Data that Human Rights Watch obtained from the UK Meteorological Office and publicly available data from the ClimateChip project, which disseminates research into the impact of climate conditions on human health, with a particular focus on heat stress, demonstrates the inadequacy of Qatar’s time and date-bound heat mitigation strategy. The data shows that the WBGT can be dangerously high in Qatar at times of the year where there is no work ban in place, notably in May, the first half of June, and September. For example, in September 2016 in Doha, the maximum WBGT in direct sunlight reached 35 and was frequently at levels where even acclimatized outdoor workers would be at serious risk in the absence of frequent breaks. Professor Tord Kjellstron, an expert in environmental and occupational heat stress, told Human Rights Watch that the risk of heat stroke was high in these temperatures: “at a WBGT of 33C, it is so hot that any physical activity, including work, is almost impossible to keep up for more than a short period of minutes.”

The data for Qatar also shows that the WBGT is dangerously high throughout the day and night between mid-June and the end of August, when the only restriction on work is the 11:30 a.m. – 3 p.m. ban. Air temperatures rarely fall below 30 degrees Celsius, and high, night-time humidity levels mean that the WBGT remains dangerously high for days or weeks on end. For example, in one 72-hour period in August 2016, the WBGT remained almost constantly above 30.6, the threshold level at which an acclimatized worker can only work safely for 30 minutes of every hour. ClimateChip data shows a steady annual increase in the mean and maximum WBGT figures for Doha.

Other experts Human Rights Watch consulted said that Qatar’s weather conditions and rudimentary regulations pose significant risks to the health of workers. Dr. Rebekah Lucas, an environmental physiologist at the University of Birmingham, reviewed data on Qatar from ClimateChip and the UK Meteorological Office. Referring to the combination of heat and humidity levels at times and dates when employers are under no obligation to provide breaks from work, she told Human Rights Watch that “workers performing moderate to strenuous labor under such adverse climate conditions are at risk of suffering acute heat-related injuries and impaired work performance.” Professor Douglas Casa, an expert in exertional heat stroke at the University of Connecticut, told Human Rights Watch that “in view of the inadequacy of Qatar’s heat policies, there is a high probability that heat stroke played a role in many of the unexplained deaths or the deaths attributed to cardiac arrest.”

In contrast to the government, Qatar’s World Cup organizers mandate work-to-rest ratios that are commensurate with the risk posed by heat and humidity, requiring supervisors to identify appropriate work-to-rest ratios using a Humidex chart. However, the Humidex chart takes no account of the effect of direct sunlight, which significantly increases the risk of heat-related illness. In addition, these requirements apply only to workers involved in World Cup projects, representing around 1.5 percent of the total number of migrant construction workers in Qatar. The Qatari authorities should extend this requirement to the general construction sector, using the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature, which as noted better measures the heat stress from the combined effect of temperature, humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation on humans, and grant outdoor workers respite from work in line with an index that accurately measures workers’ exposure to heat stress.

Investigations into Worker Deaths

Qatari authorities have failed to implement two of the key recommendations of a 2014 report the government commissioned by the international law firm DLA Piper. The report included an independent review of the legislative and enforcement framework of Qatar’s labor laws and practices, prompted by reporting by news media and research by international human rights and labor groups that pointed to abuses of migrant workers. The report noted that the number of deaths attributed to cardiac arrest was “seemingly high” and urged that the government reform its laws to mandate autopsies or post-mortem examinations into “unexpected or sudden deaths.” The other key recommendation was that the government commission an independent study into an apparently high number of deaths that authorities attributed to cardiac arrest.

Human Rights Watch has identified the failure of the Qatari authorities to perform autopsies or post-mortems on deceased foreign workers when the cause of death is unclear as a significant problem. Data from Qatar’s Supreme Council of Health for 2012 – the last year for which the Qatar government made public relatively detailed and comprehensive information about worker deaths – indicated that out of a total of 520 deaths that year of migrant workers from Bangladesh, India and Nepal – three countries that supply roughly three-quarters of Qatar’s 2 million low-paid migrant workers – 385 (74 percent) died that year from causes that the authorities neither explained nor investigated: 246 workers (47 percent) died from “sudden death, cause unknown;” and 139 (27 percent) died from “other causes.”

The Indian ambassador to Qatar, Sanjiv Arora, told the Qatari press in February 2014 that “most of the [Indian] deaths [in Qatar] are due to natural causes.” In response to a right to information request submitted by a Delhi-based organization, the Environics Trust, the Indian embassy in Qatar revealed the death toll of Indian workers in Qatar since 2011: 239 Indian workers died in Qatar in 2011, 237 died in 2012, 241 died in 2013, 279 died in 2014, and 279 died in 2015. The Indian embassy refused to respond to Environics Trust questions about the causes of these deaths, stating that the information “has been shared by the Qatari authorities in confidence.” Environics Trust has appealed the decision to India’s Central Information Commission on grounds that it is in the public interest to disclose the names and especially the causes of death of the high number of Indian nationals in one country.

A representative from the Nepal Embassy in Qatar told DLA Piper that, out of a total of 353 Nepali deaths in 2012 and 2013, “most…were a result of cardiac arrest.”

The United Kingdom-based Office of National Statistics Death Certification Advisory Group offers guidance to doctors in England and Wales on the completion of death certificates: “Terms that do not identify a disease or pathological process clearly are not acceptable as the only cause of death. This includes terminal events, or modes of dying such as cardiac or respiratory arrest, syncope or shock.” In the United States the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers similar guidance to doctors: “The mechanism of death (for example, cardiac or respiratory arrest) should not be reported as the immediate cause of death as it is a statement not specifically related to the disease process, and it merely attests to the fact of death.” A senior cardiologist in the UK, Dr. Hamish Dobbie, told Human Rights Watch said that if a doctor certified a death as “sudden death / cause unknown” in the UK, it would automatically trigger an investigation by a coroner to determine the cause of death, and that in most cases the coroner would order an autopsy.

The DLA Piper report commissioned by the Qatari government stressed the importance of collecting and disseminating data on deaths, as well as the importance of investigating “sudden” deaths and deaths attributed to cardiac arrest:

It is crucial that the State of Qatar properly classifies causes of deaths. It is critical to collect and disseminate accurate statistics and data in relation to work-related injuries and deaths. If there are any sudden or unexpected deaths, autopsies or post-mortems should be performed in order to determine the cause of death. If there are any unusual trends in causes of deaths, such as high instances of cardiac arrest, then these ought to be properly studied in order to determine whether preventative measures need to be taken.

Qatari Law no. 2 of 2012 states that “the autopsy or post-mortem examination of human bodies is prohibited unless for the purpose of determining whether death was caused by a criminal act or whether the deceased suffered from illness prior to death, or for educational purposes.” Human Rights Watch wrote to Minister of Public Health Dr. Hanan Mohamed Al Kuwari on September 28, 2016, to ask for details on how many migrant worker fatalities have resulted in autopsies or post-mortem examinations. Human Rights Watch received no response to this request or a follow up request sent on September 6, 2017.

Human Rights Watch’s letters to the minister of public health also requested information on migrant worker deaths in Qatar since 2011, broken down by year, age group, profession, and cause of death, and whether any had been related to heat stress. Human Rights Watch wrote similar letters to the Indian, Nepali, Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan, and Filipino embassies in Qatar, requested similar information on deaths of their nationals in Qatar. In view of the procedures required to attain a work visa and complete a death certificate, it is certain that all of this data exists.

In August 2017, Qatari authorities responded to Human Rights Watch with information on migrant worker deaths at the workplace resulting from injuries. This information indicates that 35 migrant workers died in 2016 as a result of serious injuries, most of them apparently sustained in the course of construction work. They did not provide information on the total number of migrant worker deaths in 2012 or since, or information on the causes of those deaths. The only other response, from the Indian embassy, referred to the press release section of their website and did not answer the questions posed.

Without this information, it is impossible to draw any conclusions on death rates relative to the size of the migrant worker population, adjusted for age, or to compare the death rates of workers employed outdoors to the death rates of workers employed indoors. Qatar is under no obligation under human rights law to report death statistics for nationals or non-nationals, but the failure of the Qatari as well as Indian, Nepali, Bangladeshi, and Filipino authorities to provide this data obstructs the most basic analysis of migrant worker deaths in Qatar.

World Cup Deaths

Out of ten worker deaths reported by the Supreme Committee between October 2015 and July 2017 on projects directly related to the World Cup, the Committee classified eight as “non-work-related,” based on the cause of death listed on the death certificates. In only one of these eight cases – the death of the 57-year-old worker on July 17, 2017 from “coronary artery disease” – did the cause of death include reference to an underlying cause.

It is standard practice in many countries for death certificates to include both the immediate cause of death as well as the underlying causes – the diseases or injuries that initiated the events resulting in death – and the latter is essential for determining whether a death was work-related.

On July 23, 2017, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Supreme Committee to ask for more precise details on all eight of the deaths they have classified as “non-work-related.” The Supreme Committee responded that “death certificates in Qatar do not include any further information on cause of death.”

In July 2016, in response to a Human Rights Watch query with regard to the April 27, 2016 death of 48-year old construction worker, Jaleshwar Prasad, the Supreme Committee stated that Prasad had fallen ill at the worksite that morning and died later that day, and that “the hospital reported the cause of death as cardiac arrest.” It added that an investigation into Prasad’s death “concluded that work duties were not a contributory factor,” but did not explain who carried out this investigation, nor how it arrived at this conclusion. The Supreme Committee’s latest Worker Welfare Progress Report, released in June 2017, stated that Prasad died of “heart failure due to acute respiratory failure.” The Committee told Human Rights Watch that they did not have records of the heat and humidity in the days before Prasad’s death. According to data from the UK Meteorological Office for April 26, 2016, the temperature spiked at 39.1 degrees Celsius in the early afternoon hours, although humidity was low. In a September 6, 2017 communication, the Supreme Committee said that they had “asked about the possibility of carrying out an autopsy, but were informed the police would only deal directly with Mr. Prasad’s employer.”

Other deaths mentioned in the June 2017 report include:

- The death of a 27-year-old Nepali worker on October 22, 2016, due to “acute heart failure due to natural causes”;

- The death of a 26-year-old Ethiopian on December 1, 2016, due to “acute respiratory failure”; and

- The death of a 25-year old Bangladeshi worker on February 4, 2017, due to “acute respiratory failure.”

On August 6, 2017, the Supreme Committee provided additional information to Human Rights Watch about deaths that occurred since the finalization of their June 2017 report:

- On May 4, 2017, a 56-year-old Indian worker died due to “heart failure due to natural causes.”

- On July 17, 2017, a 57-year-old Indian worker died due to “coronary artery disease due to hyperlipidaemia (excessive cholesterol).”

In its September 6, 2017 communication, the Supreme Committee said that outside of the officially restricted midday summer work hours, work was suspended on their projects due to high Humidex index readings for a total of 150 additional hours in 2016, and an additional 255 hours between January 1 and early September 2017. With regard to the fact that the Humidex index does not take the effect of solar radiation (sunlight) into consideration, the committee said that sunlight is “factored into the restrictions on SC project sites” but did not elaborate. The committee said it carries out “spot checks” to ensure that contractors shut down work sites when required by temperature and humidity readings.

International Law Requirements, and FIFA’s Human Rights Policies

Qatar has ratified the revised version of the Arab Charter on Human Rights. Under this charter it is, therefore, bound to respect and protect the right to life (article 5) and the right to health (article 39) of everyone in the country. It is also bound under the Arab Charter to respect the right of every worker in the country to “rules for the preservation of occupational health and safety” (article 34). Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) also affirms the rule of customary international law that “every human being has the inherent right to life.”

According to a draft general comment prepared in April 2015 by the Human Rights Committee, the body of experts charged with monitoring implementation of the ICCPR, the right to life “concerns the entitlement of individuals to be free from acts and omissions [emphasis by Human Rights Watch] intended or expected to cause their unnatural or premature death,” and implies the existence of a legal framework to ensure the enjoyment of the right to life by all individuals. The draft is still under consideration at time of writing.

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights offer guidelines specifying some of the steps businesses should follow to implement their responsibilities. As laid out in those documents, businesses should respect all human rights, avoid complicity in abuses, and adequately remedy them if they occur. These principles and guidelines apply to all relevant actors engaged in construction-related activities in Qatar or linked to preparations for the 2022 World Cup, including world football’s governing body, FIFA, and the national football associations who will participate in the tournament.

In 2015, FIFA commissioned Harvard professor John Ruggie, who developed the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, to report on its human rights policies. Professor Ruggie’s May 2016 FIFA report calls for human rights protections across FIFA’s global operations, including Qatar. In October 2016, FIFA released FIFA 2.0: The Vision For The Future, which makes human rights a central pillar. In June 2017, FIFA published its Human Rights Policy, “anchoring respect for human rights” across all FIFA operations. Under the UN Guiding Principles, FIFA is obligated to take effective steps to avoid human rights problems and ensure remedy for abuses that occur in spite of those efforts.

Human Rights Watch Recommendations:

To the Government of Qatar:

- Release data on migrant worker deaths for the past five years, broken down by age, gender, occupation, and cause of death;

- Immediately replace the summer working hours ban with a legally binding requirement that employers adequately minimize the heat-stress risk to workers, including the prohibition of work at all times of unacceptable heat risk. Engage recognized heat-stress specialists in drafting legislation, which should include meaningful sanctions for non-compliance;

- Amend Law No. 2 of 2012 on Autopsy of Human Bodies to require medical examinations and allow forensic investigations, including autopsies if necessary, into all sudden or unexplained deaths; and

- Pass legislation to require that all death certificates include reference to a medically meaningful cause of death, such as a trauma, a disease, or a pathological process.

To FIFA and National Football Associations:

- Insist that Qatar put in place reforms to protect workers from heat and other injuries, including to replace the summer working hour ban with a system that accurately reflects the actual risk to workers at any given time; and

- Insist that Qatar carry out investigations into worker deaths and make comprehensive data publicly available.

To the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy

- Use the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT), which measures the combined effect of temperature, humidity, wind speed and solar radiation, to determine thresholds for dangerous outdoor work and ban work in excess of these thresholds; and

- Implement the WBGT year-round and at all hours of the day, not just during the existing calendar-based work ban dates.