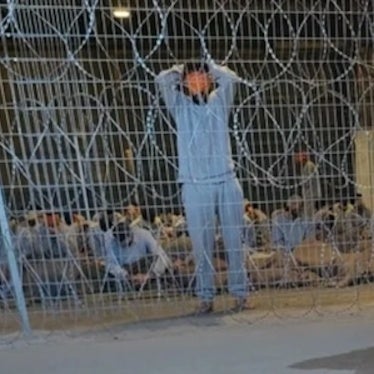

Bangladesh is the latest country to erupt in protests over economic conditions. In July, students took to the streets to protest the country's Supreme Court decision to reinstate a quota system for government jobs that they believed favored ruling party supporters. The government responded by killing over 400 protestors, fanning the flames of protest, which persisted even after the court reduced the quota. On Aug. 5, the prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, announced her resignation.

Meanwhile, in Kenya, young people have been protesting since June, when Parliament approved a tax billthat would fall hardest on the poorest. A proposed tax on menstrual pads became a symbol of how much the government was willing to squeeze people to pay off the country's debt. In July, President William Ruto sent the bill back to Parliament for revision, but pockets of protests continue, and have inspired protests in Nigeria following economic reforms that drove up the cost of living, as well as in Uganda, against government corruption.

These protests come on the heels of those that swept Pakistan and Angola over the past year in response to government cuts in energy subsidies. In 2022, demonstrations across Sri Lanka following the government's default on its debt led to the ouster of the president.

The specific triggers that set off these protests may vary, but they share a common thread—anger over an economic system that feels intolerable. The cost of living has been rising globally without a commensurate rise in wages for most people, while an increase in interest rates has forced many governments to divert a huge share of their revenues to servicing debt, eroding spending on already underfunded public services like health care and education.

But protester anger is not merely desperation over poverty. The ruling party hoarding government jobswhile gutting private sector labor protections. Cutting subsidies for electricity to pay creditors rather than enforcing tax rules for the rich. Neglect of public services amid rampant corruption. In country after country, what is making so many people, particularly young people, willing to confront the often brutal hand of the state is a collective rejection of a system that fuels inequality.

We should heed their message. Governments—and the global institutions that have a heavy hand in shaping economic policy—have, as the U.N. special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Olivier de Schutter put it, accepted that "economic growth will bring prosperity to all." In doing so, they've enabled an explosion in economic inequality.

But this approach is falling apart as the pressures of debt and climate change mount, and protesters are refusing to accept that those on the losing end of inequality should foot the bill.

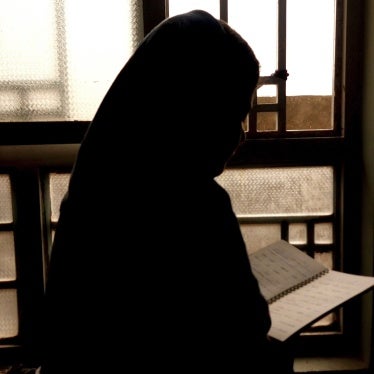

Take Bangladesh. A focus on the garment industry has brought rapid economic growth, leading many to hail the country as a development miracle. But the government lured foreign investors by collecting abysmally few taxes, a "race to the bottom" incentivized by international tax rules, and allowing companies to pay poverty wages.

As a result, Bangladesh has one of the lowest tax-to-GDP ratios in the world.

Rock-bottom revenues also pushed the Bangladesh government to seek a loan from the International Monetary Fund in 2022. It is not surprising that nearly every country affected by the recent wave of economic-triggered protests has an IMF program. But its loan conditions, although ostensibly intended to stabilize economies, often worsen poverty and inequality.

At the same time, many governments are severely constrained by an international system designed to benefit richer countries. The increase in interest rates has sent debt payments soaring, but the global system for restructuring debt is broken.

We need a new economic model rooted in respect for and promotion of human rights—a human rights economy. This concept would put respect for human rights at the center of all aspects of the global economic system, from debt to taxes to international financial institutions.

Recognizing that an obsession with growth is at odds with an environmentally sustainable economy, a human rights approach emphasizes the equitable distribution of resources that can fund realization of rights like universal access to quality health care, education, social security, and ensuring that people are paid a living wage.

The potential for such a paradigm shift is very real. Governments took a big step forward on Aug. 16 when they overwhelmingly voted in favor of terms of reference for a new U.N. treaty on tax. The treaty offers a rare opportunity to fix rules such as those that led Bangladesh to its quandary of high growth yet pitiful revenues, potentially enabling developing countries to raise billions in new revenues.

Many wealthy countries are skeptical about the treaty, but they should realize that their fate is too closely tied to that of other countries to ignore the shaking ground beneath protesters' feet. People are rising to claim their rights; they deserve more than cosmetic changes.