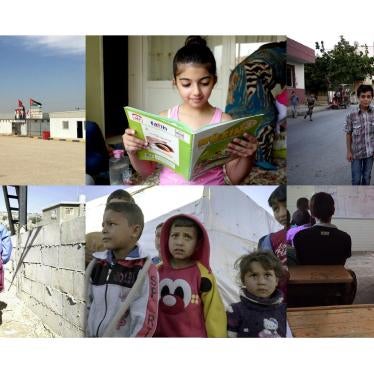

(Beirut) - The number of Syrian refugee children enrolled in school in Lebanon has stalled at the same inadequate levels as in the 2017-2018 school year, Human Rights Watch said today.

Fewer than half of the 631,000 school-age refugee children in Lebanon are in formal education, with roughly 210,000 in donor-supported public schools and 63,000 in private schools. The Education Ministry said that it was obliged to limit enrollment and cut costs due to insufficient funding from international donors.

“Every Syrian refugee child who is not in school is an indictment of the collective failure to fulfill their right to education,” said Bill Van Esveld, senior children’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “There was already an education crisis in Lebanon, yet the current school year has been marred by finger-pointing over funding and last-minute decisions that left many kids out in the cold.”

International donors have made joint pledges to support universal enrollment for Syrian refugee children and should ensure they are providing sufficient funds to reach that goal, Human Rights Watch said. They should work with Lebanon’s Education Ministry to increase accountability, transparency, and predictability in education planning.

The Education Ministry’s goal for 2018-2019 was to enroll 250,000 Syrian children, an increase of 40,000, and 215,000 Lebanese children in public schools, which would have required $149 million in donor funding. As of November, the ministry said that it had received only $100 million.

Human Rights Watch interviewed six Syrian families with a total of 14 children who could not enroll. Some said that they were not informed that new students could not enroll, or of subsequent policy changes, or whether their children would be placed on waiting lists. Human Rights Watch also interviewed Education Ministry officials, staff of nongovernmental groups and UN agencies, and donor governments that are funding education in Lebanon, but could not identify a single issue or actor responsible for the budget shortfall.

In September, the ministry decided it would not accept new Syrian students but limit enrollment to students who had previously been enrolled in public schools or completed accredited pre-primary or catch-up programs. However, many Syrian children who were in school last year did not re-enroll. The ministry extended the deadline by two weeks, to October 27, and instructed schools and nongovernmental groups to identify students who did not return. On October 20, it also eased restrictions to allow new Syrian students to enroll, so long as no new classes had to be opened to accommodate them. As of November 20, about 36,000 new students have enrolled, but 28,500 former students still had not, a ministry official said. Taking the lower enrollment numbers into account, the ministry reported in mid-November that it still faced a $30 million budget gap.

The families told Human Rights Watch that officials at a primary school in the Bekaa valley had either refused to enroll their children or accepted them but told them to leave after a few days, including one boy who had in fact been enrolled in a public school last year. Groups supporting children in the area corroborated the families’ accounts and reported similar problems at two other public schools.

In other areas, some school officials arbitrarily insisted that refugee children present documents that the Education Ministry does not require for enrollment, such as proof of legal residency in Lebanon, or asked parents to pay to enroll their children, staff at several groups said. Human Rights Watch has previously found noncompliance by some public school staff with official education policies.

Human Rights Watch was not able to determine whether any individual donors failed to meet agreed funding goals, but has documented that a lack of transparent and timely donor funding has undermined the goal of reaching Syrian refugee children with education. At a series of international conferences since 2016, Lebanese and donor government representatives have jointly agreed on the goal of universal enrollment for refugee children and on education budgets.

Some Syrian children who were denied enrollment at public schools have been left with no alternative access to education. Syrian parents whose children had been rejected by public schools told Human Rights Watch that preschool programs run by nongovernmental groups could not accept the children back, either because classes had filled up or because their children had aged out of the preschool programs. The Education Ministry generally permits nongovernmental groups to help primary-school-age children who are already enrolled in public schools, for instance with homework support, but does not permit them to teach out-of-school children in this age group.

The Education Ministry did not repeat last year’s “Back to School” campaign, in which nongovernmental groups and UN agencies had encouraged Syrian and vulnerable Lebanese families to enroll their children. The ministry said the campaign had been inefficient and that a new campaign risked enrolling children whom there were no funds to teach. But nongovernmental education providers said that the lack of a campaign contributed to poor re-enrollment this fall among children who had formerly been in school.

Other education programs have also been curtailed or interrupted, including the Accelerated Learning Program, to help children who had been out of school catch up. The ministry lost funding for the program and cut the number of students during the summer, and only received funding to continue it in November, an official said. Placement tests are due to be held in December. The program is the only way back to school for thousands of Syrian children who could not pass entrance examinations. As of November, the ministry had not reinstated a program to allow UN agencies to place Syrian volunteers as “community education liaisons” to support Syrian students at second shift schools taught in Arabic.

Some families said that the barriers to education were pushing them to think about leaving Lebanon for Syria, despite the risks involved, and that others had already left. Humanitarian organizations have also noted that limited access to education is one of the factors pushing Syrians to return to Syria despite concerns about safety.

Human Rights Watch does not have evidence that recent returns of Syrians have been forced. However, harsh living conditions, largely as a result of Lebanese policies that have restricted legal residency, work, and freedom of movement, have put so much indirect pressure on refugees that some believe they have no option but to return to a country where they face serious risks.

Lebanon should follow through on the important commitments to refugee rights that it made at a the Friends of Syria donor conference in Brussels in April, including on residency status, legal protection, education, and nonrefoulement or not returning people to places where they would be in danger.

“Many refugee children are still shut out of school in Lebanon and it’s already December, putting their future at risk,” Van Esveld said. “Donors should ensure that the Education Ministry has the promised funds to prevent a “lost generation,” while insisting on access to quality education. Parents shouldn’t be forced to decide between their kids’ education and their safety.”

Accounts from Families

Names have been changed for the protection and privacy of those interviewed.

“Sara,” the mother of two boys ages 11 and 8 in the Bekaa valley, described her desperation as October went by and they were unable to enroll in school:

I went to register them both, and at first the school told me they could begin on October 10. But then [the younger son] only went for 5 days, and the older boy went for 10 days, and the director told them to leave. “You don’t have a name here,” the director said. She meant they weren’t on the list from the ministry, or on her computer. [My older son] was told to leave in the middle of a class by his teacher, and when he went to the director and asked why, the director slapped him. He deserves to know at least why they won’t let him go to school. I tried to register them at other schools. [My older son] was a good student before, now he can’t remember how to multiply, and [my younger son] can’t even read.

“Sabrine,” 40, said that a public primary school had refused to enroll her daughters last year, saying that there was no room for them, and rejected them again this fall. “Um Ahmad,” 27, said her boys, ages 10 and 11, were both enrolled in first grade at a public school last year. This year, officials at the school allowed the older boy to register but rejected his brother, without explanation.

Some school officials who initially registered but then refused to enroll students said they were acting on verbal instructions from the Education Ministry, humanitarian groups reported.

“Awad,” 50, said that his three children, ages 7 to 10, were turned away by public school officials when they tried to register in October because they lacked certifications of previous enrollment at a public school. He said that barriers to accessing education were contributing to refugees leaving Lebanon:

The camp I’m in has 17 children who are not in school. A whole extended family went back to Syria because they wanted the kids to get an education. I think I will have to go back at the end of the year too, if I can’t get my children in school here.

Refugee Education and Funding

The Syrian conflict forced an estimated 1.5 million refugees into Lebanon, which with a population of approximately 4 million, is hosting the highest number of refugees per capita in the world.

At a conference in London in February 2016, donors and countries hosting Syrian refugees had committed to ensure that there would be no “lost generation” of children, and that $1.4 billion annually was needed to support education, primarily in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey.

At the conference, Lebanon presented an updated version of a national education plan, “Reaching All Children with Education II,” with a budgeted need of $350 million annually in donor support for five years, an overall figure that includes first and second shift enrollment costs as well as other costs. Donors and Lebanese government representatives re-committed to universal enrollment and the $350 million figure in subsequent meetings in Brussels.

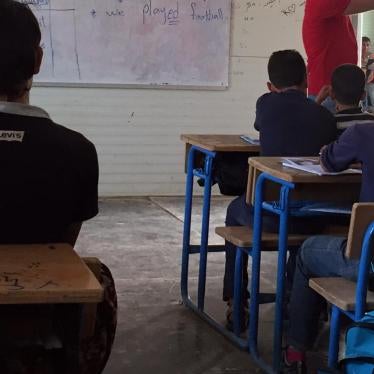

Even before the Syrian conflict, 70 percent of Lebanese parents sent their children to private schools due to concerns about the quality of the public school system. Lebanon’s public schools now have roughly the same number of Syrian and Lebanese children enrolled.

Overall, there are 631,000 refugee children in Lebanon, ages 3 to 18, who are eligible to enroll in formal education, from pre-primary through secondary school. During the 2017-2018 school year, about 213,000 Syrian refugee children enrolled in public schools, including 59,000 enrolled in “first shift” morning classes at public schools alongside Lebanese children and 154,000 in Syrian-only, “second shift” classes, which operate in the afternoons at public schools, of whom 149,000 completed the year. Another 63,000 Syrian children were enrolled in private or semi-private schools.

For the current school year, the Education Ministry reported in November that 155,000 Syrian children are enrolled in second-shift classes. Figures for Lebanese and Syrian children in the morning shift classes were not yet available. But an official estimated that the numbers in morning shift classes and private schools remain roughly equivalent to last year.

The Education Ministry said it had not repeated its “Back to School” campaign because it cost $1 million and that only 20 percent of children it reached were out of school. It said that a new campaign risked reaching children whom it had no funds to teach. Instead, the ministry said that nongovernmental groups and UN agencies should identify out-of-school children and place them on waiting lists in case more funding becomes available.

The Education Ministry said in planning documents that its goal was to increase enrollment to 250,000 Syrian children in 2018-19, at a projected cost of $135.8 million, based on previously-agreed “unit costs” of $600 per Syrian child enrolled in second shift classes, and $363 per Syrian child enrolled in first shift classes. In addition, the ministry aimed to increase enrollment of vulnerable Lebanese children from 210,000 to 215,000, at a cost of $12.9 million in donations, at $60 per child. Donor funding offsets part of the school fees that Lebanese families would otherwise have to pay. As of July, donors had contributed $100 million, leaving a budget gap of $48.7 million for the school year that began on September 25 for Lebanese children and October 10 for Syrians.

Based on current enrollment figures, the ministry reported in late November that it still faced a $30 million funding gap.

In discussing the budget shortfall, all parties mentioned an ongoing disagreement over the way the Education Ministry was using $100 out of the $600 allocated per child enrolled in second shift classes to build new schools rather than for maintenance and depreciation of existing facilities, and donors were pushing for the ministry to switch from “unit costs” per enrolled student to an overall cost for the RACE 2 program, but there was no information to show these issues were linked to the funding shortfall.