- Am 31. Oktober 2023 griffen israelische Truppen rechtswidrig ein Wohnhaus in Gaza an, das eindeutig kein militärisches Ziel war. Dabei kamen mindestens 106 Zivilist*innen, darunter 54 Kinder, ums Leben.

- Die zahlreichen israelischen Luftangriffe im Gazastreifen seit dem 7. Oktober 2023 haben Tausende von zivilen Opfern gefordert. Sie machen deutlich, welche verheerenden Folgen unrechtmäßige Angriffe mit Explosivwaffen in bewohnten Gebieten haben.

- Staaten sollten Waffenlieferungen an Israel aussetzen, sich für Ermittlungen des Internationalen Strafgerichtshofs in Palästina einsetzen und gezielte Sanktionen gegen die Verantwortlichen für Verstöße gegen das Kriegsrecht verhängen.

(Jerusalem, 4. April 2024) – Der israelische Luftangriff auf ein sechsstöckiges Wohnhaus im Zentrum des Gazastreifens am 31. Oktober 2023, in dem Hunderte von Menschen untergebracht waren, ist ein mutmaßliches Kriegsverbrechen, so Human Rights Watch heute. Mit mindestens 106 getöteten Zivilist*innen, darunter 54 Kindern, stellt er einen der Vorfälle mit der höchsten Zahl an zivilen Opfern seit Beginn der Bombardierung und dem israelischen Einmarsch in den Gazastreifen nach den von der Hamas angeführten Angriffen auf Israel am 7. Oktober dar.

Human Rights Watch hat keine Beweise dafür gefunden, dass es zum Zeitpunkt des israelischen Angriffs ein legitimes militärisches Ziel in der Nähe des Gebäudes gegeben hat. Demnach war der Angriff nach dem Kriegsrecht wahllos und damit unrechtmäßig. Die israelischen Behörden haben keine Gründe für den Angriff genannt. Angesichts dessen, dass das israelische Militär es in der Vergangenheit vielfach versäumt hat, mutmaßliche Kriegsverbrechen auf glaubhafte Weise zu untersuchen, ist es umso dringender, dass der Internationale Strafgerichtshof (IStGH) eine Untersuchung schwerer Verbrechen einleitet, die von allen Konfliktparteien begangen wurden.

„Bei Israels rechtswidrigem Luftangriff auf ein Wohnhaus am 31. Oktober wurden mindestens 106 Menschen getötet, darunter Kinder, die Fußball spielten, Anwohner, die ihre Telefone in einem Lebensmittelgeschäft im Erdgeschoss aufluden, und vertriebene Familien, die sich in Sicherheit bringen wollten“, sagte Gerry Simpson, stellvertretender Direktor für Krisen und Konflikte bei Human Rights Watch. „Dieser Angriff hat massenhaft zivile Opfer gefordert, ohne dass ein militärisches Ziel erkennbar war. Er war einer von zahlreichen Angriffen mit einem hohen Blutzoll, der noch einmal verdeutlicht, wie wichtig eine Untersuchung durch den Internationalen Strafgerichtshof ist.“

Zwischen Januar und März 2024 sprach Human Rights Watch am Telefon mit 16 Personen über den Angriff vom 31. Oktober auf das Wohngebäude und den Tod ihrer Angehörigen und anderer Personen. Darüber hinaus wurden Satellitenbilder, 35 Fotos und 45 Videos von den Folgen des Angriffs sowie weitere relevante Fotos und Videos in sozialen Medien analysiert. Human Rights Watch war es nicht möglich, den Ort des Anschlags zu besichtigen, da die israelischen Behörden seit dem 7. Oktober praktisch alle Grenzübergänge zum Gazastreifen blockiert haben. Israel hat in den letzten 16 Jahren wiederholt Anträge von Human Rights Watch auf Zugang zum Gazastreifen abgelehnt.

Berichten von Zeug*innen zufolge hielten sich am 31. Oktober in dem Wohnhaus, das auch Ingenieursgebäude genannt wurde, südlich des Flüchtlingslagers Nuseirat 350 oder mehr Menschen auf. Mindestens 150 von ihnen suchten dort Schutz, nachdem sie aus ihren Häusern in anderen Teilen des Gazastreifens geflohen waren.

Ohne Vorwarnung trafen gegen 14.30 Uhr innerhalb von etwa 10 Sekunden vier Raketen das Gebäude, wodurch dieses vollständig zerstört wurde.

Zwei Brüder berichteten, wie sie aus ihren nahegelegenen Häusern herbeigeeilt seien, um nach ihren beiden Söhnen und einem Neffen zu suchen, von denen sie wussten, dass sie draußen Fußball spielten. Einer der Männer sagte, er habe seinen 11-jährigen Sohn unter Resten von Betonstahl in den Trümmern gefunden: „Sein Hinterkopf war aufgerissen, eines seiner Beine schien kaum noch mit dem Körper verbunden zu sein, und ein Teil seines Gesichts war verbrannt, aber er schien zu leben. Wir konnten ihn innerhalb von Sekunden befreien, aber er starb noch im Krankenwagen. Wir haben ihn noch am selben Tag beerdigt.“ Alle drei Jungen starben bei dem Angriff.

Keine*r der befragten Zeug*innen gab an, vor dem Angriff eine Warnung der israelischen Behörden zur Evakuierung des Gebäudes erhalten oder davon gehört zu haben.

Anhand von Gesprächen mit Angehörigen einiger Todesopfer, darunter 34 Frauen, 18 Männer und 54 Kinder, hat Human Rights Watch die Identität von 106 getöteten Personen bestätigt. Die Gesamtzahl der Toten ist aller Wahrscheinlichkeit nach höher. Airwars, eine Nichtregierungsorganisation, die zivile Schäden in Konfliktgebieten untersucht, ermittelte in frei zugänglichen Materialien 112 Namen von getöteten Personen. 96 dieser Namen decken sich mit den von Human Rights Watch identifizierten Personen. Airwars‘ Untersuchungen zufolge starben 19 weitere Personen, deren Namen der Organisation zwar nicht bekannt sind, die jedoch von ihren Familienmitgliedern identifiziert wurden.

Human Rights Watch befragte zwei Personen, die an der Bergung von Leichen aus den Trümmern des Gebäudes beteiligt waren. Sie sagten, dass sie am Nachmittag des Angriffs zusammen mit anderen dabei halfen, etwa 60 Leichen zu bergen. In den folgenden vier Tagen hätten sie zusammen etwa 80 weitere Leichen geborgen. Eine dritte Person sagte, sie sei noch 12 Tage nach dem Anschlag daran beteiligt gewesen, Leichen aus den Trümmern zu bergen. Es ist möglich, dass noch weitere unter den Trümmern begraben sind.

Die israelischen Behörden haben keine Informationen über den Angriff veröffentlicht, auch nicht über das beabsichtigte Ziel und etwaige Vorsichtsmaßnahmen zur Minimierung des Schadens für die Zivilbevölkerung. Ein Schreiben von Human Rights Watch vom 13. März, in dem die Organisation ihre Untersuchungsergebnisse zusammengefasst und um spezifische Informationen gebeten hat, ließen sie unbeantwortet.

Das Kriegsrecht verbietet Angriffe, die auf Zivilpersonen und zivile Objekte gerichtet sind, bei denen nicht zwischen Zivilpersonen und Kombattant*innen unterschieden wird oder von denen zu erwarten ist, dass sie Zivilpersonen oder zivilen Objekten einen Schaden zufügen, der in keinem Verhältnis zum erwarteten militärischen Vorteil steht. Zu wahllosen Angriffen gehören Angriffe, die nicht auf ein bestimmtes militärisches Ziel gerichtet sind oder bei denen eine Methode oder Kampfmittel eingesetzt werden, deren Folgen nicht wie erforderlich minimiert werden können. Parteien in einem bewaffneten Konflikt müssen alle durchführbaren Vorkehrungen treffen, um den Schaden für die Zivilbevölkerung so gering wie möglich zu halten. Dazu gehört auch, dass sie die Zivilbevölkerung wirksam vor Angriffen warnen, es sei denn, die Umstände lassen dies nicht zu. Und sie müssen die Zivilbevölkerung, die unter ihrer Kontrolle steht, von den Auswirkungen der Angriffe verschonen. Schwere Verstöße gegen das Kriegsrecht, die von Einzelpersonen in krimineller Absicht, also vorsätzlich oder rücksichtslos, begangen werden, stellen Kriegsverbrechen dar.

Da der Angriff auf das Wohngebäude nicht auf ein militärisches Ziel gerichtet war, ist er vorsätzlich oder wahllos und damit unrechtmäßig, so Human Rights Watch. Dass das Gebäude viermal getroffen wurde, deutet stark auf einen vorsätzlichen Angriff hin und schließt aus, dass die Munition fehlgeleitet war oder es durch einen anderen Fehler zu dem Schaden kam. Und selbst wenn es ein legitimes militärisches Ziel gegeben hätte, müsste der Angriff angesichts der offensichtlich zu erwartenden hohen Zahl an zivilen Personen in und um das Gebäude auf seine Verhältnismäßigkeit hin untersucht werden.

Seit den von der Hamas angeführten Angriffen auf den Süden Israels am 7. Oktober, bei denen mehr als 1.100 Menschen getötet und etwa 240 weitere als Geiseln genommen wurden, ist der Luftangriff einer von Hunderten von Angriffen des israelischen Militärs auf Gaza, bei denen palästinensische Zivilist*innen getötet oder verletzt wurden. Airwars hat glaubhaft berichtet, dass bei 195 wahrscheinlichen Angriffen des israelischen Militärs zwischen 1 und 9 Zivilist*innen getötet wurden, bei 107 Angriffen zwischen 10 und 59 und bei 4 Angriffen zwischen 60 und 139. Bis zum 1. April hatte Airwars auch vorläufige Informationen über zivile Opfer bei weiteren 3.358 Angriffen gesammelt, bei denen es sich höchstwahrscheinlich ebenfalls um israelische Luftangriffe handelte.

Diese Angriffe zeigen erneut die verheerenden Schäden für die Zivilbevölkerung und die erhöhte Gefahr unrechtmäßiger Angriffe, wenn Sprengwaffen mit großflächiger Wirkung in dicht besiedelten Gebieten eingesetzt werden. Alle Staaten sollten das Abkommen gegen den Einsatz von Explosivwaffen in Wohngebieten vom November 2022 unterzeichnen.

Das Gesundheitsministerium in Gaza berichtete, dass zwischen dem 7. Oktober 2023 und dem 31. März 2024 mehr als 32.000 Menschen in Gaza getötet wurden, darunter mehr als 13.000 Kinder und 9.000 Frauen, 75.000 wurden verletzt. Allein im März kamen bei Angriffen mindestens 2.400 Menschen ums Leben. In den Statistiken wird nicht zwischen Kombattant*innen und Zivilist*innen unterschieden.

Die Zeitung Haaretz berichtete im Februar, das israelische Militär untersuche „Dutzende von Fällen“, in denen seine Streitkräfte möglicherweise gegen das Kriegsrecht verstoßen hätten. Es ist nicht klar, ob der Angriff auf das Wohngebäude am 31. Oktober dazugehört.

Israels Verbündete sollten die Militärhilfe und Waffenlieferungen an Israel aussetzen, solange israelische Truppen ungestraft systematisch und wiederholt mit Angriffen auf die palästinensische Zivilbevölkerung gegen das Kriegsrecht verstoßen. Staaten, die weiterhin Waffen an die israelische Regierung liefern, riskieren eine Mitschuld an Kriegsverbrechen. Sie sollten ihren Einfluss geltend machen, unter anderem durch gezielte Sanktionen, um die israelischen Behörden dazu zu bringen, den schweren Verstößen ein Ende zu setzen.

„Die erschütternde Zahl an palästinensischen Todesopfern, zumeist Frauen und Kinder, zeigt die Missachtung des zivilen Lebens mit tödlichen Folgen und weist auf viele weitere mögliche Kriegsverbrechen hin, die untersucht werden müssen“, sagte Simpson. „Andere Regierungen sollten die israelische Regierung auffordern, die unrechtmäßigen Angriffe zu beenden. Sie sollten Waffenlieferungen an Israel sofort einstellen, um das Leben von Zivilisten zu retten und eine Mitschuld an Kriegsverbrechen zu vermeiden.“

Weitere Informationen zu dem Angriff auf das Wohngebäude und anderen israelischen Luftangriffen finden Sie weiter unten in englischer Sprache.

Hostilities between Israel and Palestinian Armed Groups

On the morning of October 7, 2023, Hamas-led fighters breached the fences separating Israel and Gaza, and entered southern Israel. They attacked at least 19 kibbutzim, 3 moshavim (collective communities), 2 cities, a music festival, and a beach party, where they deliberately killed civilians, and also attacked military bases. At least 1,100 people were killed, the majority of them civilians, according to Israeli officials.

The attackers took about 240 people hostage, including children, people with disabilities, and older people. Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups in Gaza have also since October 7 launched thousands of rockets at Israeli towns, violating the prohibition against indiscriminate attacks on civilians and civilian objects. The deliberate killing of civilians and captured combatants, taking of hostages, and indiscriminate rocket attacks are serious violations of the laws of war that are war crimes.

The hostilities that began on October 7, like the fighting in 2008, 2012, 2014, 2018, 2019, and 2021, took place amid Israel’s sweeping, unlawful closure of the Gaza Strip, which began in 2007. Human Rights Watch determined in 2021 that the Israeli government’s repressive rule over Palestinians amounts to the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution.

During previous hostilities, Israeli forces repeatedly carried out indiscriminate airstrikes that killed and injured numerous civilians – wiping out entire families – with no evident military targets in the vicinity. Strikes have targeted and destroyed high-rise towers in Gaza full of residences and businesses.

Since October 7, the Israeli authorities have cut off essential services, including water and electricity, to Gaza, which constitutes collective punishment, and blocked the entry and distribution of life-saving assistance, including food, water, and medicine, which are war crimes. The World Health Organization (WHO) warned on January 31 that the population of Gaza is “starving to death.” Human Rights Watch has documented that the Israeli government is using starvation as a weapon of war, a war crime.

The Israeli military has reported that between October 7 and February 20, it carried out 31,000 airstrikes in Gaza. Israeli airstrikes have hit large residential buildings, food aid distribution centers, medical facilities, humanitarian worker residential compounds, schools, shelters, universities, water infrastructure and wells, and reduced large parts of neighborhoods to rubble, including in attacks that were apparently unlawful and should be investigated as possible war crimes. Israeli forces have also unlawfully used white phosphorous in Gaza. Amnesty International has also documented airstrikes killing civilians.

The primary United Nations aid agency for Palestinian refugees, the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), estimated that as of mid-March, about 1.7 million people in Gaza had been displaced from their homes: about 75 percent of Gaza’s population of 2.3 million. Israeli military authorities have ordered the majority of Gaza’s population to evacuate their homes, risking the war crime of forced displacement.

On October 10, the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry stated that there was “clear evidence” of war crimes in Israel and Gaza and that it would share information with relevant judicial authorities, including the International Criminal Court.

Israeli Airstrike on the Engineers’ Building

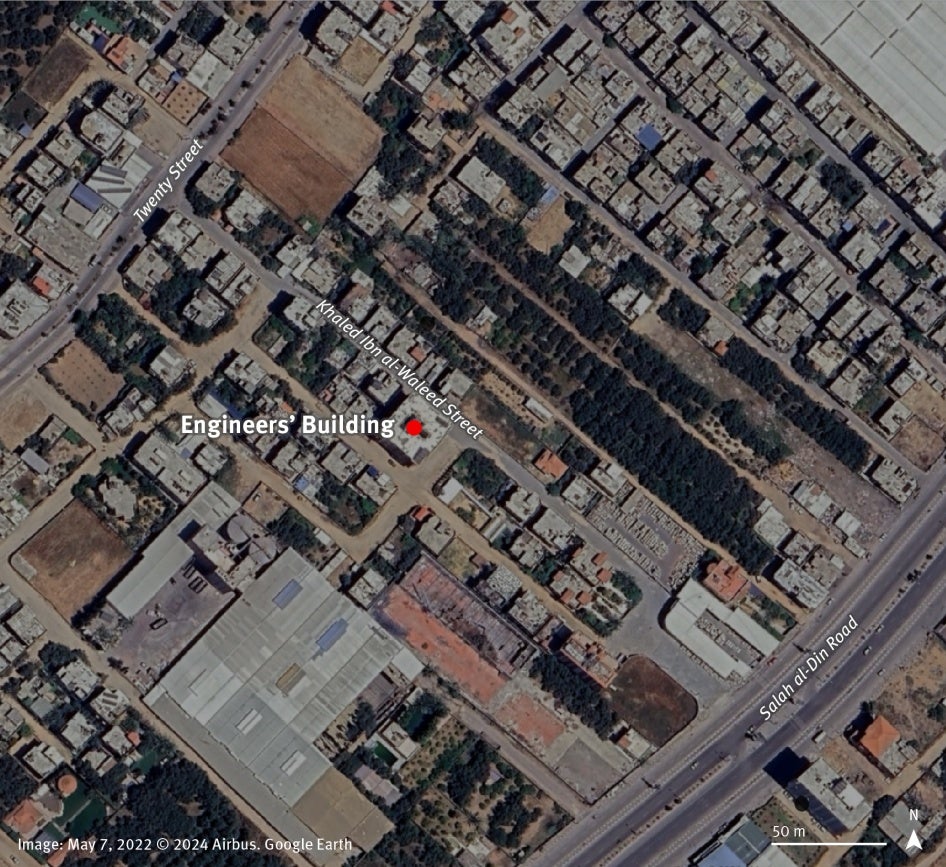

At about 2:30 p.m. on October 31, an Israeli airstrike involving four munitions struck and destroyed the six-story Mohandiseen (Engineers’) Building, also known as the Engineers’ Tower, according to witnesses. The building was in a residential area, about 400 meters from the southern limits of the Nuseirat refugee camp in central Gaza. The Human Rights Watch investigation found no indication of a military objective in or near the building on October 31.

Human Rights Watch spoke by phone with 16 people who had knowledge of the attack. Seven described what they saw during and immediately afterward, including one survivor who was in the building, three who were in their homes nearby at the time of the attack and who lost relatives, two who lost relatives and who lived in the building but had left just before the attack, and one who lived nearby who didn’t lose any relatives in the attack. Human Rights Watch also spoke with five relatives of people killed who live outside Gaza. Four other people who lived near the building but who did not see the aftermath, including one who lost relatives in the attack, also gave researchers the names of people whom they learned had been killed.

Human Rights Watch confirmed the identities of 106 people killed in the attack, and 2 of those injured, through interviews with their relatives. The dead include 34 women, 18 men and 54 children. The injured include a 17-year-old girl and a woman.

103 of the dead were from 14 families that were staying in the building. The other three, from two other families, were the boys who lived about 60 meters away and had been playing football in the street.

Airwars reviewed social media and other open sources for information about the attack, and found mentions of the names of 112 people killed, as well as mentions of 19 other people identified only through their relationship to other victims in their family. These include 42 women, 22 men, 62 children, and 5 people whose ages are unknown. Airwars also found in open sources the names of 6 people who were injured. The dead are from 22 families.

Both organizations identified 96 of those killed by name, while Airwars alone identified an additional 15 by name, and Human Rights Watch alone identified an additional 9 by name.

The two organizations between them identified 136 people killed in the attack: 44 women, 22 men, 65 children, and 5 people whose age is unknown. They were from 24 families: Abu Daqqa, Abdeljawad, Abdelrahman, Abdo, Abu Jazar, Abu Jiyab, Abu Saeed, Agha, Ali, Dabaki, Farkh, Hanafi, Ijla, Jweifel, Kuhail, Mabhouh, Mubasher, Quqa, Sadoudi, Saleha, Shaheen, Sharif, Thawabta and Younis.

Human Rights Watch was unable to establish how many of the bodies were recovered and how many remain under the rubble. It is possible, though unlikely, that people whose bodies were not recovered survived and relocated elsewhere in Gaza without their families’ knowledge.

The Engineers’ Building: Sheltering, Serving Hundreds

Verified photographs of the Engineers’ Building posted online prior to the attack show a six-story building, 25 by 25 meters, and about 20 meters high.

Residents and others familiar with the building said it had 20 apartments of about 150 square meters on five floors, which were full of people during the hostilities. In the early afternoon, the small ground-floor grocery store was usually thronged with people wanting to charge their phones there amid Israel’s electricity cuts. The store could offer this service because the building was partially powered by 16 solar panels on its roof. The ground floor also had a gym, a poultry shop, and a video games arcade.

While the origin of the building’s name is unclear, no accounts suggested that the building was being used for engineering purposes. One resident said that the building got its name from the engineers’ union that built it for its members. Another said the building was owned by an engineering consultancy office. A third person said that many of the engineers and their families who had originally lived in the building had since moved out, leaving three known engineering families, and that over time other people had moved in.

Based on interviews and other sources, Human Rights Watch estimates that as of October 31, at least 350 people were staying in the building, including about 125 people known to have been crammed into just 5 apartments. The total includes at least 200 residents and at least 150 displaced Gaza residents, including dozens sheltering in the gym. Some of the displaced people sheltering in the building had followed the Israeli military’s October 13 directive to residents of northern Gaza to move south of Wadi Gaza, a coastal wetland that cuts across Gaza from west to east. They included at least 23 members of an extended family who fled Gaza City and who were all killed in the attack: Eman Khaled Abu Said, her husband, their two children, and her parents, as well as five of her siblings and 11 other relatives. Human Rights Watch obtained from Eman Abu Said’s sister, Israa Abu Said, the names of 23 members of the extended family who were killed in the attack.

It is unclear how many people were in the building, including at the grocery store, at the time of the attack.

Streets Filled with Children Playing at Time of Attack

Neighbors said that streets near the Engineers’ Building were bustling with local residents just before the attack.

Rami Abdo, who lived about 60 meters away, said that about half an hour before the attack, one of his sons, Mohammed Rami Abdo, 11, and two of his nephews, Mohammed Hatem Abdo, 13, and Mohammed Nidal al-Mabhouh, 8, had gone outside to play football with dozens of other children just outside one of the entrances to the building. All three boys died in the attack.

A local resident said that just before the attack, the building was the only place in the area that had electricity and that she saw many people charging their phones in the grocery store.

The Attack and Its Immediate Aftermath

Ameera Shaheen, her husband, daughter and parents had fled their home in al-Moghraqa village in central Gaza the day before the attack after the Israeli military told residents to evacuate the area. They moved into a third-floor apartment in the Engineers’ Building where her aunt, Wafa’ Shaheen, her family of four and about 15 other relatives were staying. She said:

There was nothing worrying at all before the attack. Almost all of us were sitting in two rooms, one for men and one for women. Some of us were laughing. We had just baked bread. There were no signs or warning or any feeling of danger. We felt safe because it was an apartment building full of civilians.

Suddenly, there was an explosion and we started screaming. I remember thinking it hadn’t destroyed the building. And then I was falling, and then I lost consciousness. I woke up later that day in the al-Aqsa Martyr’s Hospital. I only had bruises. I don’t remember anything about waking up, but my relatives told me that I started screaming and calling for my daughter, asking them to go and rescue her although she was sitting there next to me, on my hospital bed.

Shaheen said that the attack killed 20 of her relatives, including 6 women, 7 men, and 7 children.

Hatem Abdo, who lived about 60 meters from the building, said the last time he saw his 13-year-old son, Mohammed, was an hour or so before the attack when he left the house:

Mohammed always used to play football in the street close by with his cousins and other children. At about 2:30 p.m. I was napping at home. Suddenly there were four explosions, with about two or three seconds between each blast. After the first explosion, I woke up and looked out of the window.

I saw about 50 children and some young men in the street, near the southern side of the Engineers’ building. I saw that the northern side of the building had been hit. Immediately, the second bomb hit the southern side, which I could see clearly from my home. I saw debris from the building falling and trapping about 20 of the children, as well as some of the adults.

Then the third bomb hit the top of the building, right in the middle, and the entire building came down, causing a huge black cloud of smoke and dust. It smelled like gunpowder. Then, the fourth one hit, which I didn’t see because of all the dust and smoke.

His brother, Rami Abdo, who lived with his family in the apartment below, was also at home at the time of the attack and said his son was playing football with his cousins and other children outside. He said he heard four explosions “which happened almost at the same time” and that the glass and debris from their building injured two of his daughters in the living room.

Another woman who lived about 30 meters away said she heard “three or four loud bombs explode.”

Both Rami and Hatem Abdo ran out of their building moments after the attack to find the young boys from their families. When they reached the street in front of the destroyed building, Rami said he saw “about 20 burned bodies” in the street, including the bodies of 3 children he recognized from the Abu Rahma family, who he said lived in the building. Hatem said he saw “dozens of bodies in the street,” some near and partially under the rubble of the building next to where it had stood, while others were dozens of meters away.

Both men then found their sister’s son, Mohammed Nidal al-Mabhouh, 8, who was still alive but badly burned, and they took him to an ambulance, which transported him to al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in Deir al-Balah. He died about eight weeks later. They then found Rami’s son, Mohammed Rami Abdo, 11, under concrete bars in the rubble of the building. Although the men said they quickly freed Mohammed, he died in an ambulance shortly afterward.

Both men then searched for Hatem’s son, Mohammed Hatem Abdo, 13, but could not find him. While looking for him, they helped carry the dead to waiting ambulances. Hatem estimated he helped carry about 60 bodies, mostly children and women, most found on the southern side of the building, including some recovered from rubble on the street. Medics later informed Hatem that his son had been found dead in the street, about 100 meters from the building.

Naheed Mahmoud lived close to the Engineers’ Building after fleeing her home. She lost six of her nieces, a nephew, and her sister’s mother-in-law in the attack. Her sister, Ola Mahmoud Jweifel, 39, and Ola’s only surviving daughter, Nada Hisham Jweifel, 17, who had moved into an apartment on the fourth floor of the Engineers’ Building in July 2023, were injured, with Nada requiring over 10 surgeries to one of her legs. As soon as the third or fourth explosion had happened and it was clear that the attack was over, Naheed ran to the building to find her sister and her sister’s children:

I was screaming and yelling and so was everyone else. The area was immediately filled with people, journalists, and civil defense [body providing emergency services and rescue], so we couldn’t reach the building. The situation was terrible. People were trying to free those trapped under the rubble using anything they could.

After some time, someone told me they found my sister Ola under the rubble. It took until about four hours after the attack to free her. She had a broken pelvis, a broken spine, a broken clavicle bone, and her whole body was black and blue from [being bruised by] the rubble. Then they said they had found her daughter, my niece, Nada. Her upper body was visible, but her lower body was crushed under the rubble. One of her legs was split open from top to bottom. Her blood was everywhere. She was in severe pain, yelling and screaming, and the other leg started to get bigger and bigger. It took until about 11 p.m. that night to free her.

Human Rights Watch spoke with Karam al-Sharif, an UNRWA employee, who lost five of his children and five other relatives in the attack. Three photographs taken by an Associated Press photographer on October 31 at the destroyed Engineers’ Building show al-Sharif standing in the rubble on October 31, holding one of his 18-month-old twin boys who were killed. The Associated Press also reported on the deaths of four of the five children who were killed.

Thirty-five photographs and 45 videos posted on social media and by media outlets and verified by Human Rights Watch show many victims and survivors and the Engineers’ Building reduced to rubble, with significant debris on the northeast, southeast and southwest sides of the building. Human Rights Watch matched the nearby buildings, trees, and roads visible in the footage with satellite imagery to confirm they showed the attacked building. Human Rights Watch also verified an aerial video that showed the building completely flattened. A photograph posted to Facebook on October 31, taken from the Salah al-Din Road approximately 225 meters southeast of the building, shows two large, dark columns of smoke rising from the location of the Engineers’ Building.

Satellite imagery taken at 10:23 a.m. local time on October 31 shows no signs of damage. Imagery taken at 10:18 a.m. local time on November 1 shows that the building is destroyed.

Human Rights Watch determined that the building most likely sustained direct hits from four air-launched munitions. Human Rights Watch found no evidence of remnants at the scene that might have helped identify the weapon. However, the blast damage and the resulting demolition of the building is consistent with the explosive payload of large air-delivered munitions. Witnesses described four munitions striking the building in quick succession, demolishing it. This is consistent with the Israeli military’s past targeting and destruction of buildings through the use of large, air-dropped munitions.

No Known Military Target

Everyone Human Rights Watch interviewed who knew the building well said they were not aware of Palestinian fighters or military equipment in or near the building at the time of the attack. The Human Rights Watch analysis of 80 photographs and videos, as well as satellite imagery of the building and surrounding area, also provided no indication of any Palestinian armed groups’ presence or of military equipment in or near the building at the time of the attack.

All those interviewed said they were unaware of any victims or survivors of the attack who were associated with any armed group. Human Rights Watch found no evidence that any of the victims were combatants. Human Rights Watch reviewed the Telegram channels and associated social media channels of both Hamas’ armed wing, Izz a-Din al-Qassam Brigades, and Islamic Jihad’s armed wing, al-Quds Brigade, two of the main groups involved in the October 7 attacks in Israel. Neither of them mentioned the October 31 strike.

The Israeli military has presented no information that would demonstrate the existence of a military target or other military objective within or near the building. The military has also not said why circumstances did not permit providing an effective advance warning to the residents of the building, and nearby buildings, to evacuate before the attack.

On February 6, Haaretz reported that the Israeli military had begun investigating “dozens of cases” in which its forces may have violated the laws of war. They include an airstrike at around 3:30 p.m. on October 31, about an hour after the Engineers’ Building attack, which the Israeli military said targeted Ibrahim Biari, commander of Hamas’ Jabalia Brigade. The attack in the Jabalia refugee camp, about 14 kilometers northeast of the Engineers’ Building, killed Biari and at least 126 civilians, including 69 children, and injured 280, according to Airwars.

Recovery and Burial of Bodies

Human Rights Watch interviewed three people involved in recovering bodies from the rubble of the Engineers’ building.

Hatem Abdo and Rami Abdo said that they helped recover between 60 and 70 bodies on the afternoon of October 31, and that they recovered about 80 more bodies over the next 4 days. Hatem Abdo said that many were laid out in the street in front of his home until they were taken away. He said relatives of the missing and others collected money to buy diesel fuel so that an excavator, which arrived on November 1, could work for between three and four hours each day to remove rubble.

Hatem said that when the excavator stopped its work, he heard from other people that 56 people were still missing. “They just vanished,” he said.

Majdi Salha fled his nearby home in mid-October, after an attack almost hit his building, and he moved with his family into his brother-in-law’s apartment in the Engineers’ Building. He left the building a few minutes before the attack, which killed 16 of his relatives: his wife and 5 of their daughters; his wife’s brother, his wife’s brother’s wife, and 5 of their children; and his wife’s sister and 2 of her children. He said:

Before I left the apartment to buy bread, I gave my youngest daughter, Lana, who was 10 years old, some money to go after lunch to buy some things in the grocery store on the ground floor of the building. Someone later told me she had gone to the store just before the attack happened.

For 12 days, I helped recover bodies from the rubble. I contributed my own money for fuel to power the excavator. We found almost all the bodies of my family members on days five, six, and seven after the attack happened. But we only found Lana’s body under the rubble on day 10. I think other bodies remained under the rubble after the excavator stopped doing its work.

Another person said he had heard that the people recovering bodies could not retrieve the bodies of the people who had been on the lower levels of the building, so the building “became a graveyard.”

Satellite imagery shows that the removal of rubble stopped between November 7 and 11. The same amount of rubble visible in imagery from November 11 appears in imagery taken on March 12, 2024.

Some people interviewed said they took bodies to or found relatives’ bodies in al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in Deir al-Balah, about four kilometers southwest of the building. One of the men who recovered bodies said that all the bodies recovered from or near the Engineers’ Building were taken to the al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital for identification and registration before burial. Human Rights Watch was unable to obtain a list of people killed in the attack who were registered at that hospital.

Television news reported from al-Aqsa Martyrs hospital on October 31 that “ambulances are still recovering the injured and moving them to [the] hospital” and that the initial group of ambulances had brought 45 victims to the hospital.

A man said he had been told that very badly injured victims were taken to the European Hospital in Khan Younis. Five people said their relatives were buried variously in al-Nuseirat refugee camp, al-Buriej refugee camp, the town of Zawaydeh, and in al-Maghazi cemetery. Majdi Salha said that between November 1 and 13, he went to the burials of 100 people who were killed during the attack on the Engineers’ Building in al-Maghazi cemetery.

Human Rights Watch verified 12 videos and a photograph posted on social media platforms that show the removal of six bodies, including two children and an older woman, from the rubble of the Engineers’ Building; five bodies on stretchers being removed from the building; and two bodies of children taken to the hospital after the attack. They also show an older woman who is either dead or unconscious being carried on a stretcher.

Another video, filmed by the journalist Motaz Azaiza and posted to Instagram on October 31, shows what appears to be a small, burned body wrapped in a sheet. Azaiza narrates that the body of a child was being removed from the second floor of a building next to the Engineers’ Building. The camera pans to a bedroom in that building and shows a child’s race-car-shaped bed partially covered by rubble.

Human Rights Watch verified three videos and a photograph that show the result of a caesarean section performed at al-Aqsa Martyrs hospital on one of the deceased victims in an unsuccessful attempt to save her baby. Human Rights Watch also verified eight videos that show seven injured people, including four children and one woman, being rescued from the Engineers’ Building.

Accountability Initiatives

On May 27, 2021, the UN Human Rights Council established a Commission of Inquiry to address violations and abuses in the Occupied Palestinian Territory and Israel. On October 10, 2023, the commission announced that it was “investigating possible international crimes and violations of international human rights law committed in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory since 7 October 2023” and that it would “continue sharing information collected with the relevant judicial authorities, especially with the International Criminal Court.”

The ICC prosecutor, Karim Khan, confirmed that his office has, since March 2021, been conducting an investigation into alleged atrocity crimes committed in Gaza and the West Bank since 2014, and that his office has jurisdiction over crimes in the current hostilities between Israel and Palestinian armed groups that covers unlawful conduct by all parties. He visited Israel and Palestine in December.

Governments should publicly express their support for the ICC in delivering impartial justice, including in its investigation of the situation of Palestine, and commit to ensuring that the ICC has the political, diplomatic and financial support it needs to carry out its global mandate.

Separately, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on January 26 and on March 28 issued provisional measures as part of a case brought by South Africa alleging that Israel is violating the Genocide Convention. The court adopted measures that include requiring Israel to prevent genocide against Palestinians in Gaza, enable the provision of basic services and humanitarian assistance, and prevent and punish incitement to commit genocide. Human Rights Watch has found that Israel is not complying with at least one of the court’s binding orders by continuing to obstruct the provision of basic services and the entry and distribution within Gaza of fuel and lifesaving aid.

National judicial authorities should also investigate and prosecute those implicated in serious crimes in the Occupied Palestinian Territory and Israel under the principle of universal jurisdiction and in accordance with national laws. Governments should impose individual sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, against officials and individuals credibly implicated in the commission of grave abuses.

The UN Secretary-General should also include Israel in the list of those responsible for grave violations against children, annexed to his 2024 annual report to the Security Council on children and armed conflict, for violations including killing and maiming.

Arms Transfers

Numerous UN special rapporteurs, independent experts and working groups issued a statement on February 23 that the transfer of weapons or ammunition to Israel that would be used in Gaza would most likely violate international humanitarian law and needed to cease immediately. Providing arms that knowingly and significantly would contribute to unlawful attacks can make those providing them complicit in war crimes.

The Dutch Court of Appeal ordered the Netherlands on February 11 to halt its export of F-35 fighter jet parts to Israel, given the clear risk they might be used in committing serious violations of international humanitarian law in Gaza. The Dutch government is appealing this decision. Canada’s foreign minister said on March 20 that Canada will continue to freeze new arms export permits to Israel, following the passage of a nonbinding House of Commons resolution calling for “ceasing the further authorization and transfer of arms exports to Israel to ensure compliance with Canada’s arms export regime.”

The Biden administration issued a National Security Memo in February that establishes that the United States Departments of State and Defense will receive written assurances from countries that receive US military assistance that they use US-origin “defense articles” in compliance with international law and that they have not arbitrarily impeded or delayed US-funded or supported humanitarian assistance during 2023. Based on their observations and investigations in Gaza, however, Human Rights Watch along with Oxfam have concluded that any assurances made by Israeli officials to use US weapons in compliance with international and US law are not credible.

On February 13, the State Department said it was using established procedures relating to the use of US-supplied weapons to investigate civilian harm caused by several Israeli attacks in Gaza but that it could not comment on specific cases under review.

The US, the United Kingdom, Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Denmark and other countries have continued to provide Israel with unconditional arms transfers and other security assistance. By granting export licenses to Israel, including for weapons identified as most likely to be used by the Israeli military in violation of the laws of war, these governments are ignoring the mounting evidence of serious violations, including the strike on the Engineers’ Building.