Summary

We’re dying from inhaling the industries’ pollution. I feel like it’s a death sentence. Like we are getting cremated, but not getting burnt.

—Sharon Lavigne, 71, Saint James Parish, January 2023

Sharon Lavigne, 71, lives in the small community of Welcome in the state of Louisiana, United States. Like many of her neighbors, the retired special education teacher has placed a sign in her front yard which reads, “We live on death row.” It is a morbid twist on the nickname by which their region has come to be more broadly known: “Cancer Alley.”

Welcome sits in St. James Parish in the heart of Cancer Alley, an approximately 85-mile stretch of communities along the banks of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge where people live on the frontlines of some 200 fossil fuel and petrochemical operations — reportedly the largest concentration of such plants in the Western Hemisphere.

Residents of Cancer Alley are the victims of deadly environmental pollution from the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry. They face severe health harms including elevated burdens and risks of cancer, reproductive, maternal, and newborn health harms, and respiratory ailments. These harms are disproportionately borne by the area’s Black residents.

State and federal authorities have failed to properly regulate the industry, and they have not made information about risks to human health readily available.

For decades, the state of Louisiana, and the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) in particular, has repeatedly failed to address the harms of fossil fuel and petrochemical operations, to enforce the minimum standards set by the federal government, and to protect the environment and human health. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has not adequately ensured that federal laws and mandates are enforced in Louisiana, and as such, is failing to protect the air, land, water, and health of Louisiana residents from harms caused by the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry.

The prevalence of harm from the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry in Louisiana indicates that both state and federal authorities are failing to respect, protect, and fulfil the human rights to life, health, access to information, and the right to freedom from discrimination on the basis of race.

Not far from Lavigne’s house, Janice Ferchaud, 66, sits in the trailer that has served as her home since her house was rendered uninhabitable by Hurricane Ida in August 2021. She wants the world to understand what is happening in Cancer Alley. She grows impatient with talking and aggressively pulls down the collar of her pink T-shirt to display her jagged mastectomy scars, the outcome of a surgery following a breast cancer diagnosis. Human Rights Watch interviewed many other Cancer Alley residents who also shared her frustration born of telling and retelling personal accounts of death, disease, and community-wide suffering and failing to see action.

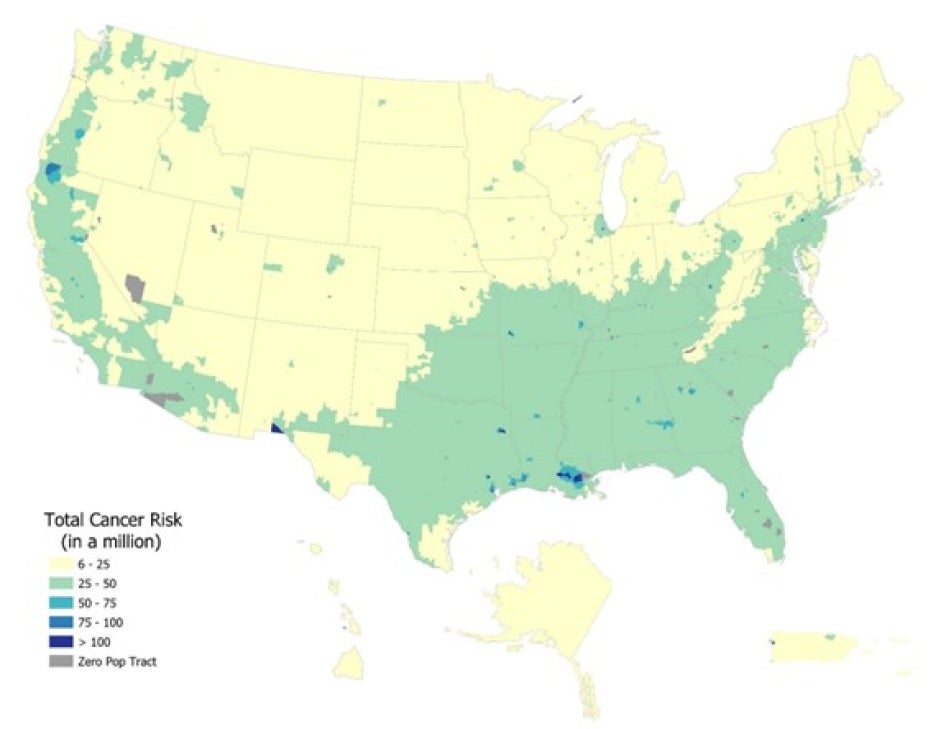

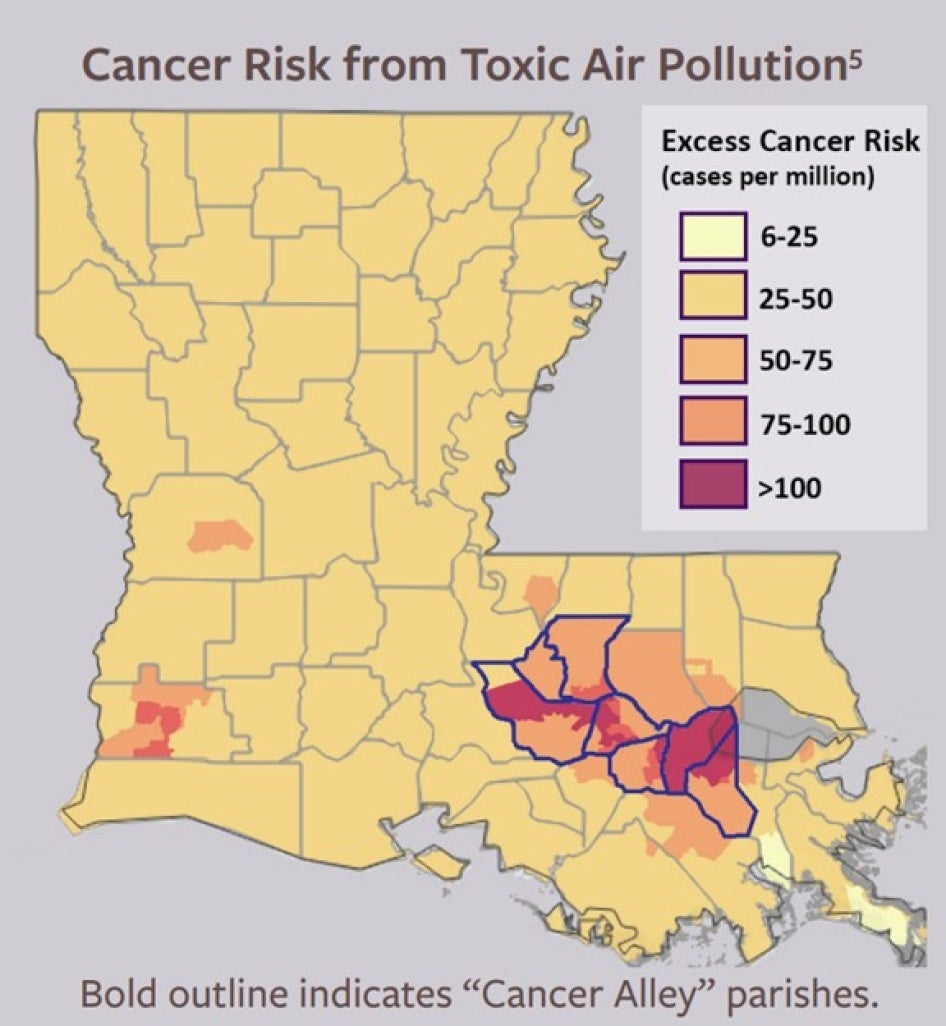

Residents of Cancer Alley face significant risks of cancer and other severe health ailments as a result of emissions from fossil fuel and petrochemical plants, according to Human Rights Watch research, including an analysis of EPA data. The area with the highest risk of cancer from industrial air pollution in the US — more than seven times the national average — is located in Cancer Alley where Robert Taylor lives. Taylor, 83, described the cases of dozens of family members and neighbors who have died or been diagnosed with cancer, including both his mother and wife. The Lavignes and Ferchauds are Black, like nearly 90 percent of their neighbors in Welcome, as are Taylor and 60 percent of his neighbors in St. John, compared to 13.6 and 33 percent of the populations of the US and Louisiana, respectively.

Throughout Cancer Alley, there is clear evidence of a disproportionate burden of harms placed on the area’s Black and low income residents from the polluting emissions of fossil fuel and petrochemical operations, including elevated cancer rates, among many other health problems.

Between September 2022 and January 2024, Human Rights Watch interviewed 70 people, including 37 Cancer Alley residents, and current and former officials of EPA, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), physicians, academics, lawyers, health care providers, advocates, and representatives of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in the region. In addition, Human Rights Watch examined scientific literature on health harms reported in Cancer Alley.

Human Rights Watch visited the nine Cancer Alley parishes: Ascension, East Baton Rouge, Iberville, Jefferson, Orleans, St. Charles, St. James, St. John the Baptist, and West Baton Rouge. Human Rights Watch observed fossil fuel and petrochemical plants located alongside or nearby playgrounds, schools, senior centers, homes, farms, and businesses. These operations were observed regularly and routinely emitting large burning flares, releasing plumes of black and brown polluting smoke, displaying stains from crude oil spilled from massive storage tanks, and releasing noxious smelling fumes. At least a dozen facilities reported to EPA their release of toxic pollution in amounts that exceeded federal legal limits established to protect public health and the environment.

In line with existing evidence linking fossil fuel and petrochemical pollution with increased risk of severe health harms, Cancer Alley residents shared with Human Rights Watch accounts of cancer diagnoses, including breast, prostate, and liver cancers. Women discussed personal stories of maternal, reproductive, and newborn health harms, as well as those of immediate family members, friends, or neighbors, including low-birth weight, preterm birth, miscarriage, stillbirths, high risk pregnancy and birth, and infertility.

New research presented for the first time in this report and currently under peer review for publication in Environmental Research: Health journal finds that people living in those areas with the worst air pollution in Louisiana, which includes many parts of Cancer Alley, had rates of low birthweight as high as 27 percent, more than double the state average (11.3 percent) and more than triple the US average (8.5 percent).[1a] Preterm births were as high as 25.3 percent, nearly double the state average (13 percent) and nearly two-and-a-half times the US average (10.5 percent).

Severe respiratory ailments were also extremely common among those Cancer Alley residents Human Rights Watch interviewed, including chronic asthma, bronchitis and coughs, childhood asthma, and persistent sinus infections. Residents said these ailments added stress to already at-risk pregnancies, resulted in children being rushed to emergency rooms and kept inside to avoid polluted air, missed days of work and school, sleepless nights due to wracking coughs, and the deaths of family members and friends.

Local human rights advocates and global institutions, including United Nations officials, have condemned the abuses and injustices perpetrated by the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry in Cancer Alley and other similarly impacted parts of Louisiana for more than two decades and have called on local, state, and national authorities for remedy. The pressure has contributed to some policy changes, but far greater action is required by all levels of US government today.

In 2022, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment identified Cancer Alley as one of several global “sacrifice zones,” among the most polluted and hazardous places on earth, illustrating egregious human rights violations. “The continued existence of sacrifice zones is a stain upon the collective conscience of humanity,” the special rapporteur wrote, representing “the worst imaginable dereliction of a State’s obligation to respect, protect and fulfill the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment.”

The United States has one of the most regulated fossil fuel and petrochemical industries in the world, but for a variety of reasons documented in this report, these regulations have been insufficient and poorly enforced. Yet expansion is underway with at least 19 new fossil fuel and petrochemical plants planned for Cancer Alley, including within many of the same areas of poverty and high concentrations of people of color, and near the homes of residents including Sharon Lavigne and Janice Ferchaud. New facilities are also planned for other areas of the state already heavily burdened by the industry, including five in Calcasieu Parish. In total, 10 are already being prepared for construction.

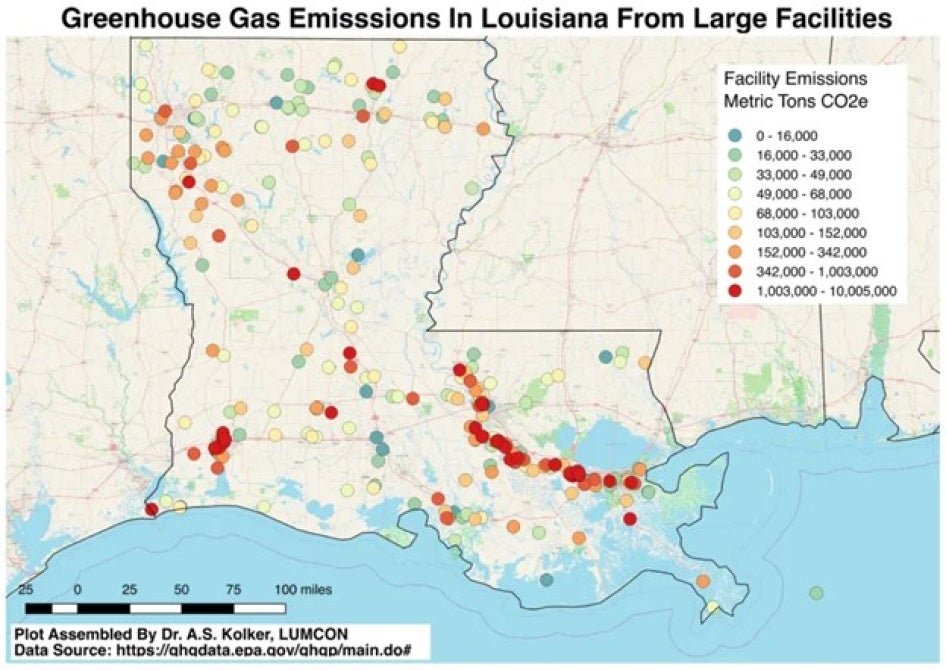

In 2020, 66 percent of Louisiana’s reported annual greenhouse gas emissions were produced by some 150 industrial facilities in Cancer Alley, virtually all of which are fossil fuel and petrochemical operations. These same facilities released 522 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions from 2016 to 2021, or the equivalent of the annual releases of 140 coal-fired power plants.

Fossil fuels are the primary driver of the climate crisis. The US is the world’s largest oil and gas producer and accounts for the greatest share—more than one-third—of all planned global oil and gas expansion through 2050, totaling nearly 73 gigatons of CO2, the equivalent of 454 new coal plants. The largest buildout of fossil fuel and petrochemical operations in the US is taking place in Louisiana and neighboring Texas.

The International Energy Agency has warned against any new fossil fuel projects if countries are to meet existing climate targets and avert the worst consequences of the climate crisis. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world’s leading authority on climate science, has called on governments to scale up renewable energy, and prioritize equity, climate justice, social justice, and inclusion to ensure that a just, rights-respecting transition is achieved.

In Cancer Alley and wherever these operations continue, local, state, and federal authorities should support moratoria on new or expanded fossil fuel and petrochemical operations. They should limit the areas where these operations can take place and require and ensure that operators implement practices and procedures that protect the human rights of frontline communities, including by enacting and effectively enforcing regulations and taking immediate and comprehensive action to deter and remedy violations.

In Louisiana, the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) should deny permits in already overburdened communities. The EPA should use its authority under the Clean Air Act to order fossil fuel and petrochemical facilities posing an imminent and substantial endangerment to human health and the environment to immediately pause all operations until they can operate in accordance with the law, object to permits which would result in a disproportionate burden of harm in already overburdened communities, and initiate an investigation into withdrawal of state authorization for Louisiana’s Clean Air Act program.

To uphold their human rights obligations, all governments should rapidly phase out fossil fuels.

To facilitate the transition away from these operations, Human Rights Watch recommends a Federal Fossil Fuel and Petrochemical Remediation and Relocation Plan (modeled on the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act programs) whereby companies operating in Cancer Alley and across Louisiana would work with community-based organizations to employ local workers and provide decommissioning and remediation services for the safe and efficient phase-out of fossil fuels. Under the plan, companies working jointly with the state and federal government would also support residents who want to leave by providing them with buyouts and relocations following all international human rights norms and best practices for relocation.

To reinforce the commitment that federal, state, and local government will respect, protect, and fulfil the human rights of Cancer Alley and all US residents, the US Congress should ratify the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Achieving the recommendations detailed in this report requires the ongoing support of frontline communities. The same Louisiana communities that have been on the frontlines of fossil fuel operations the longest have also spent decades resisting and devising not only alternatives, but also paths to deliver them. Louisiana in general and Cancer Alley in particular have been home to key community-based leaders and developments in the US and global environmental and climate justice movements. They have modeled leadership and local, national, and international coalition building. But additional support is sorely needed — to uplift their efforts, facilitate their access to policymakers and the public, enable their long-term sustainability, and help them to access and use resources for effective advocacy.

“I’ve been told to sit down and stop fussing,” breast cancer survivor Genevieve Butler, 66, of St. James Parish, told Human Rights Watch. “But I’m not going to sit down because there’s too much at stake.”

Glossary

Air monitor: Air measurement device to determine levels of emissions of different pollutants from industrial operations which can be placed at different locations, such as within smokestacks or on the external wall or “fenceline” where it borders a local community.

Cancer Alley: Widely used nickname given to an area along the Mississippi River in the US state of Louisiana between New Orleans and Baton Rouge where communities live alongside some 200 fossil fuel and petrochemical plants. Alternatively referred to as the “Industrial Corridor.”

Environmental Justice: The environmental justice movement grew out of a response to the system of environmental racism. The EPA defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, culture, national origin, income, and educational levels with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of protective environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” This definition relies on disproportionate outcomes, rather than merely discriminatory intent, with EPA regulations prohibiting practices that “have a discriminatory effect,” even if those practices are “neutral on their face.” Each federal agency is mandated to “make achieving environmental justice part of its mission.”

Fenceline communities: Communities located “on the fence line” — that is, adjacent to — highly polluting facilities and directly affected by the operations of those facilities.

Flaring: When fossil fuel and petrochemical operators burn off excess methane gas rather than contain or capture it in pipelines. When burned, the powerful greenhouse gas — more than 80 times more potent at global warming than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period — is released into the atmosphere. Flaring also releases toxic pollutants known to harm human health, including benzene, a human carcinogen that can cause leukemia.[1]

Fossil fuels: Non-renewable natural resources, namely oil, methane gas, and coal.

Industrial Corridor: An alternative to “Cancer Alley” often used by Louisiana’s state government.

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG): Methane gas that has been cooled to a liquid state, at about -260 degrees Fahrenheit (-161.5 degrees Celsius), for shipping and storage.

Methane gas: Also known as “natural gas,” a gaseous fossil fuel primarily composed

of methane.

Oil refinery: A facility which converts crude oil into petroleum products for other uses, including as fuels for transportation, heating, paving roads, generating electricity, and as feedstocks for petrochemicals.

Overburdened communities: The EPA uses the term to refer to the low‐income, tribal, Indigenous and other people of color communities that potentially experience disproportionate environmental harms and risks due to exposures or cumulative impacts or greater vulnerability to environmental hazards, generally from industrial polluters. This increased vulnerability may be attributable to an accumulation of negative and lack of positive environmental, health, economic, or social conditions within these populations or communities.

Petrochemical Plants: Petrochemicals are chemicals derived from fossil fuels. Petrochemical plants use fossil fuel byproducts and convert them into compounds which they (or other plants) use in the manufacture of products, such as single use plastics, rubber, and synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Virtually all industrial chemicals are derived from fossil fuel fuels and are thus “petrochemicals.”[2]

Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) Program: Primary regulatory tool for accessing industry emissions of toxic chemicals, this EPA program tracks industrial management of the highest emitting facilities which provide a self-accounting of the volume of certain hazardous pollutants released on a site-by-site basis.

Recommendations

To the US Federal Government and the State of Louisiana

● Implement moratoria on new or expanded fossil fuel and petrochemical operations and begin phase-out of existing operations.

● Support a fair and equitable transition for workers, communities, and industry away from fossil fuels and petrochemicals toward a renewable green economy.

● Work with businesses that shut down to jointly pay for local workers to remediate sites, restore waterways and lands, and foster greater community resilience by building localized small-scale renewable energy sources.

● Allocate funding to community-based organizations for public and health care provider awareness and outreach campaigns on the health harms of exposure to fossil fuel and petrochemical operations, including maternal, reproductive, and newborn health, cancers, and respiratory ailments.

● Enact federal and state legislation (or amend the state constitution) to recognize the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment.

To the US President

● Direct all relevant federal agencies to develop and implement a Federal Fossil Fuel and Petrochemical Remediation and Relocation Plan modeled on Inflation Reduction Act programs. The plan should create incentives for companies to work with community-based organizations to employ local workers to decommission and remediate operations and support relocation of those residents who desire to do so. Any relocation under the plan should follow international human rights norms and best practices.

● Direct all relevant agencies to reject federal permits for new or expanded fossil fuel projects.

● Submit the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities to the Senate for its advice and consent to ratification.

To the US Senate

● Consent to ratification of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

To the US Environmental Protection Agency

● Object to permits for fossil fuel and petrochemical operations that would result in a disproportionate burden of harm in already “overburdened communities,” defined by the EPA as those already experiencing disproportionate environmental harms and risks due to exposures or cumulative impacts or greater vulnerability to environmental hazards.

● Order fossil fuel and petrochemical operations that pose an imminent and substantial endangerment to human health and the environment to immediately pause all operations until they operate in accordance with the law.

● Implement periodic review periods of delegations of power to state agencies to better enforce implementation of federal standards.

● Update the Clean Air Act National Emissions Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants by mandating that all petrochemical and fossil fuel operations have fenceline air monitors and make data immediately publicly available, install leak detection systems which alert the public, limit excessive flaring, and take immediate and comprehensive action against violators.

● Update the Clean Water Act Effluent Limitation Guidelines to place stronger limits and controls on pollution from fossil fuel and petrochemical operations.

● Fully enforce all federal environmental laws in Louisiana with increased monitoring, investigation, oversight, and appropriate actions to compel compliance, including through the Office of External Civil Rights Compliance and by referring criminal violations to the US Attorney for prosecution.

● Initiate an investigation into withdrawal of state authorization for Louisiana’s Clean Air Act program under the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality.

● Initiate a renewed investigation into statewide failure to enforce Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and other federal nondiscrimination laws by the Louisiana Departments of Environmental Quality and Health.

● With the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), fund a community-led participatory comprehensive door-to-door epidemiological health survey of census tracts where residents face the highest pollution burdens in Louisiana, including Cancer Alley, focused on proximity to polluting operations.

To the Government of Louisiana

● Support a fossil fuel phase-out.

● Support local demands for parish-wide moratoria on new or expanded industrial operations, including all fossil fuel and petrochemical operations.

● Deny permits for fossil fuel and petrochemical operations that would result in a disproportionate burden of harm in already overburdened communities.

● Require all petrochemical and fossil fuel facilities to have fenceline air monitors and make data immediately publicly available, install leak detection systems which alert the public, limit excessive flaring, and take immediate and comprehensive action against violators.

● Install community air monitors for all six National Ambient Air Quality Standard criteria pollutants throughout areas in which residents face the highest pollution burdens, make data immediately publicly available.

To Fossil Fuel and Petrochemical Companies Operating in Louisiana

● Operate within all local, state, and federal laws, including those related to pollutant emissions.

● With local community-based organizations and federal agencies, support residents with buyouts and relocations following all international human rights norms and best practices; provide decommissioning and remediation services for a safe and efficient phase out of fossil fuels.

To Public and Private Healthcare Institutions and Providers

● Educate providers and resource patients about the health risks associated with exposure to fossil fuel and petrochemicals, including maternal, reproductive, and newborn health, cancer, and respiratory ailments.

● Provide accessible and affordable health services to treat specific health harms associated with fossil fuels and petrochemicals throughout Cancer Alley and Louisiana.

● Adopt US Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Sector Climate Pledge to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 and increase climate resilience.

Methodology

This report is based primarily on individual in-person interviews conducted with residents throughout Louisiana’s Cancer Alley during three reporting missions in 2023: January 25-February 3, March 19-30, and May 9-18. A total of 70 interviews were conducted for this report. Detailed interviews were conducted with 37 residents of Cancer Alley, including nine who have worked in the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry, an additional three residents of other heavily fossil-fuel and petrochemical impacted areas of the state in Mossville and Lake Charles; and with 30 elected officials and other government representatives, including five former high-ranking officials within the EPA, one of whom also worked for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, physicians, academics, lawyers, healthcare providers, advocates, and members of nongovernmental organizations. Research was conducted from September 2022 to January 2024.

Human Rights Watch conducted research within nine parishes of Cancer Alley: Ascension, East Baton Rouge, Iberville, Jefferson, Orleans, St. Charles, St. James, St. John the Baptist, and West Baton Rouge. Parishes in Louisiana are functionally equivalent to counties elsewhere in the US. Human Rights Watch traveled throughout the two major cities and dozens of small largely rural communities which line River Road along the Mississippi River and into dozens of homes of residents, religious services, community organizing meetings, picnics, press conferences, court hearings, a legislative session at the State Capitol, a historic plantation honoring the history of the enslaved, graveyards, public spaces outside of dozens of fossil fuel and petrochemical operations, and a guided tour of the last remaining 11 miles along the Mississippi River in Saint John the Baptist Parish without heavy industry.

Residents interviewed include 28 Black and one white woman, ages 31 to 86 years, and 11 Black men, ranging in ages from their early twenties to 83 years.

Some interviews were conducted by phone, including with residents of Calcasieu and Cameron Parishes. All people interviewed provided oral or written informed consent to participate and no compensation was provided for any interviews.

Interviews were consistent with existing research on the extensive human rights harms associated with fossil fuel and petrochemical operations, including increased risks of cancer, maternal, reproductive, and newborn harm, severe respiratory and other ailments resulting from exposure to the toxic and other harmful pollution emitted from these operations.

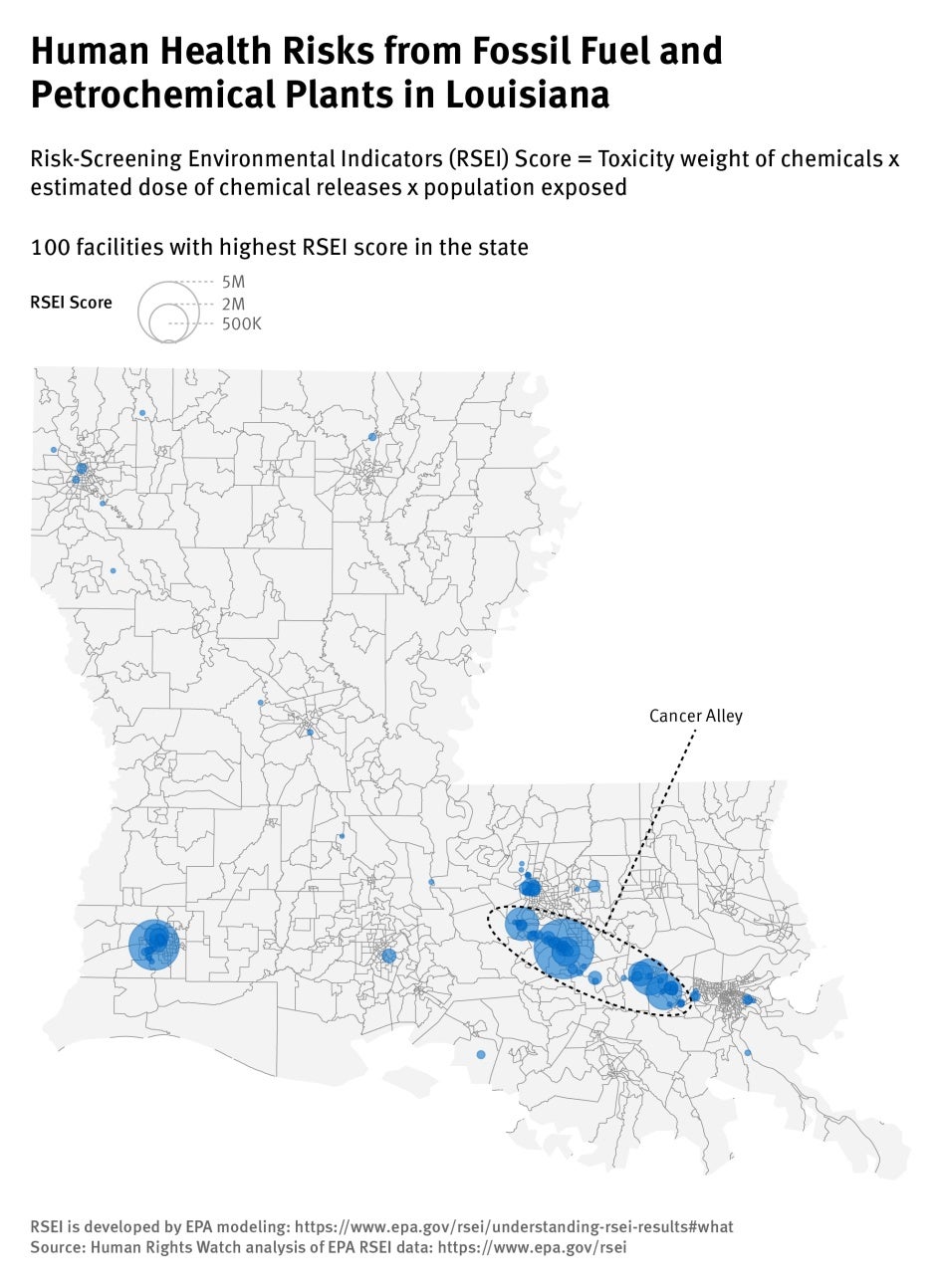

Human Rights Watch conducted analysis of Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators (RSEI) data from US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and US Census Bureau population data. The RSEI score uses data reported by facilities on chemical releases, factors in the toxicity weights of those specific chemicals, models how chemicals move and change in the environment, and considers the size of the population exposed to these chemicals (within 3 mile radius).[3] Human Rights Watch categorized the Louisiana facilities that report to the EPA on whether they are fossil fuel or petrochemical facilities, including those, such as synthetic fertilizer and pesticide plants, which use fossil fuels as a significant input in the manufacturing process. The facilities that report to the EPA for RSEI scores do not include all fossil fuel or petrochemical facilities within Cancer Alley or Louisiana, rather, only those that report to the EPA Toxic Release Inventory (TRI). TRI reporting forms must be filed by owners and operators of facilities that: fall within a TRI-covered industry sector or is federally-owned or operated; has 10 or more full-time employee equivalents; and manufactures (including import) or processes more than 25,000 pounds or otherwise uses more than 10,000 pounds of a TRI-listed chemical during a calendar year.

In October 2023, Human Rights Watch wrote to the US Environmental Protection Agency, the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, and the Louisiana Department of Health. All three agencies responded. The letters and replies are included in Annex A and Annex B.

Every resident of Cancer Alley interviewed for this report is a descendant of a family that has resided in the area for generations, grew up there, and has spent all or most of their lives in the area. Many are direct descendants of people who were enslaved to work on plantations or worked on fields that were formerly plantations following emancipation.

I. Background

Our lot in life is to intercede for Louisiana,

Swallow all the spit, slime, vomit and despair

That comes to us…

down the long spine of Mother River.

We brush our teeth with dead oil

And flush our guts with sulfur dioxide

That we might be a worthy sacrifice.

—Excerpt from “Ascension Parish,” by Barbara Malaika Favorite

Louisiana’s Toxic Legacy

The Mississippi River travels southeast across Louisiana, cutting a diagonal path through the state capitol in Baton Rouge, on to the River Parishes and New Orleans before heading out to the US Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. The Chitimacha and Choctaw people lived along the banks of the Mississippi for thousands of years before European plantation owners violently took their land, relying on a brutal and entrenched system of slavery for labor.[4] Native Americans were among the enslaved, but it was the hundreds of thousands of Africans captured from their homes in Senegambia, the Bight of Benin, the Bight of Biafra, and West-Central Africa who for generations endured violence and cruelty, providing the bulk of Louisiana’s enslaved labor.[5]

Fossil fuels — oil, methane gas,[6] and coal — are non-renewable natural resources. The global fossil fuel industry traces its roots to Louisiana. Home to one of the world’s first productive oil wells in 1901,[7] nearly 40 years later, it was the site of the world’s first offshore oil well.[8] As production boomed, oil refineries were built to turn oil into motor fuels and other petroleum products while extracting compounds such as ethane, propane, and methane. Petrochemical plants took these fossil fuel byproducts and converted them into ethylene, propylene, methanol, and other petrochemicals for use in the manufacture of other products, such as single use plastics, rubber, and synthetic fertilizers and pesticides.[9] Virtually all industrial chemicals are derived from fossil fuels and are thus more accurately referred to as petrochemicals.[10]

As the plants arrived along the Mississippi River beginning primarily in the 1960s, many took and retain today the names of the plantations on which they were built. Many “Free Towns” founded by formerly enslaved people, including Morrisonville,[11] Reveilletown,[12] and Sunrise,[13] were taken over by industry, their residents pushed or forced out, and largely erased.

For decades, these fossil fuel and petrochemical operations were largely unregulated. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was not established until 1970, the Clean Water Act was not enacted until 1972, and the Clean Air Act did not fully come into effect until 1976. Louisiana’s first air pollution regulations were introduced in 1972, and the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) was only established in 1984.[14]

As early as the 1970s, residents, workers, and researchers began investigating and exposing toxic emissions and environmental and public health harm from these operations.[15] A 1987 Washington Post article captured the fallout in what is likely the first national publication to refer to “Cancer Alley,” describing a human health and environmental calamity due to fossil fuel and petrochemical operations, reporting that the “air, ground and water along this corridor are … full of carcinogens, mutagens and embryotoxins.” The article quotes Dr. Velma Campbell, an occupational health physician at the Ochsner Clinic in New Orleans, identifying a "positive correlation" between high cancer rates and the industry’s pollution and suggesting that residents have been subjected to a "massive human experiment" in which "large quantities of a wide variety of substances have been discharged into the air and water. Now we are standing back and seeing what the outcome will be." Nonetheless, the article concluded, “No one is recommending the shutdown of companies so vital to Louisiana's fortunes.”[16] That has changed.

But, while resistance grew, so too has the industry’s hold on the state. Louisiana is a global epicenter for fossil fuel and petrochemical operations. The most active methane gas market center in North America — the Henry Hub in Erath, Louisiana — is where nine interstate and three intrastate pipelines interconnect.[17] US liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports more than doubled from 2020 to a record high in 2022, and Louisiana handled almost two-thirds of those shipments with plans for massive expansions underway.[18]

The US is the world’s largest oil and gas producer,[19] and Louisiana is one of the nation’s largest oil- and gas-producing states. It is home to two so-called “carbon bombs,” the world’s largest fossil fuel production projects with reserves so large that were they to be completely extracted and burnt they could emit more than one gigaton of carbon dioxide (CO2) each.[20] The first is in the US Gulf of Mexico and the second is in the northwestern corner of Louisiana known as the “Haynesville Shale.” Production is booming in both areas.[21]

Louisiana has the highest per capita energy consumption in the US largely due to the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry itself. With 15 oil refineries[22] and nearly 450 petrochemical plants[23], all of which consume enormous amounts of energy, some 15 percent of the total methane gas consumption in the state is used to simply produce and distribute more oil and gas. Meanwhile, energy for homes accounts for just 7 percent of the state’s total consumption.[24]

Unlike the rest of the US, Louisiana’s industrial operators are the largest contributor to its carbon footprint.[25] Petrochemical and fossil fuel operations dominate the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, which are on the rise, reaching around 141 million metric tons in 2018 — the highest level since at least 2000.[26] The largest and majority of greenhouse gas emissions are from facilities in Cancer Alley.[27]

Operations in Cancer Alley now total some 200 primarily fossil fuel and petrochemical plants. These include oil refineries, petrochemical plants, oil storage tank farms, and fertilizer and pesticide manufacturers that use fossil fuels as their primary feedstock. There are others, such as plants that produce steel and aluminum which burn large amounts of fossil fuels to power their operations.

The Mississippi River cuts through the middle of these operations, functioning as a dump site for chemical waste and a mass transit route, carrying barges loaded with open piles of coal, tankers filled with oil, gas, and petrochemicals, and ships shuttling cargo out to the offshore industry in the Gulf.

Pollution

We are a sacrifice zone.

– Tish Taylor, Saint John the Baptist Parish, March 2023

Louisiana has the worst pollution of any state in the United States, according to an analysis of 2021 EPA chemical release data conducted by US News & World Report.[28] That year, residents were, on average, exposed to nearly four times more industrial toxic pollutants in their air, land, and water than the national average, with 3,533 pounds per square mile of industrial toxins versus a national average of 926.[29] Per capita, Louisiana residents also faced the nation’s highest risk of long-term chronic human health effects from toxic chemical pollution.[30]

The fossil fuel and petrochemical industries are the worst polluters in the state,[31] contributing more to toxic and harmful air pollution[32] and greenhouse gas emissions than any other industry, and are the second leading source of water pollution, a good deal of which is dumped directly into the Mississippi River in Cancer Alley.[33] The majority of toxic air and greenhouse gas emissions also occurs in Cancer Alley,[34] which has the state’s highest concentration of fossil fuel and petrochemical operations.

Under the US Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, the EPA regulates emissions of hazardous air and water pollutants. It maintains a publicly available Toxics Release Inventory (TRI), in which the highest emitting facilities provide a self-accounting of the volume of certain (not all) hazardous pollutants they release on a site-by-site basis. TRI is the primary tool used by all levels of government to determine industry emissions of toxic pollutants.

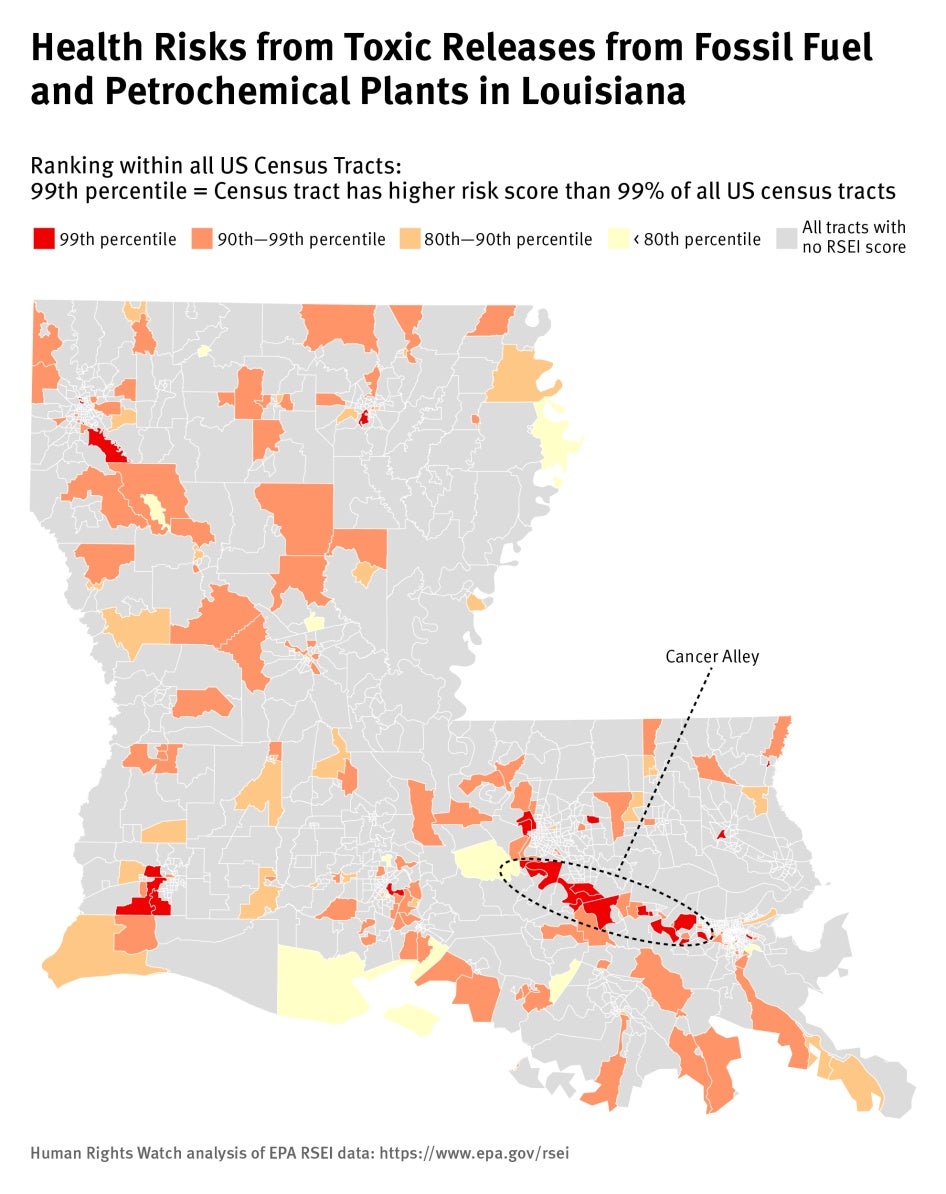

The EPA found in 2016 and again in 2020 that residents of Cancer Alley were exposed to more than 10 times the level of health risk from hazardous air pollutants than residents living elsewhere in the state.[35] Black residents in Cancer Alley face even higher rates of exposure than white residents, with the most polluting operations disproportionately concentrated within Black communities.[36] For example, while no new fossil fuel and petrochemical facilities have been built in the majority-white communities in St. James Parish over the last 46 years, new projects have been built and continue to be approved in the majority-Black districts.[37]

For decades, nearly every census tract in Cancer Alley has ranked in the top 5 percent nationally for cancer risk from toxic air pollution and in the top 10 percent for respiratory hazards.[38] The EPA has also attributed reproductive harm, among other risks, to toxic air pollution in Cancer Alley.[39]

EPA data also reveal levels of toxic emissions in Cancer Alley from fossil fuel and petrochemical operations that exceed regulatory limits. The EPA provides on its website information for the last three years on compliance with the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) (which includes the storage, transportation, and disposal of hazardous waste, including petroleum).[40]

Human Rights Watch reviewed these data for the three-year-period from October 2020 through November 2023 for twelve fossil fuel and petrochemical plants operating in Cancer Alley located nearby interviewees. Only one of these facilities was reported in compliance with all three federal laws during the entire three-year period, while “significant violations” (the highest level of violation) were common among all 12. Only two of the facilities were in compliance with the Clean Water Act during the entire three-year period, with three plants facing periods of “significant violation.” Four of the facilities were in “significant violation” of the Clean Air Act in every reporting period of the last three years, three of which were also simultaneously in “significant violation” of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act in every period. Another refinery was in “significant violation” of the Clean Air Act for seven of the last twelve periods. One plant, further flagged as in “high priority violation” of the Clean Air Act, had faced six formal enforcement actions in the last three years, for a total of just $300 in penalties.[41]

TRI data reveal that the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry release a range of hazardous and toxic pollutants into the air, water, and on land in Cancer Alley.[42] These pollutants include polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs),[43] a group of highly toxic compounds with potential health effects including cancer, reproductive harms, birth defects, respiratory disease, autoimmune disease, and neurological effects[44]; and “volatile organic compounds” (VOCs),[45] including benzene, toluene, and xylene. VOCs can contribute to the formation of ozone[46], an important component of smog, which can in turn cause dangerous, acute, and chronic health conditions such as asthma, lung infections, bronchitis, and cancer.[47]

Human Rights Watch reviewed 2021 EPA TRI Explorer Releases by geography and Waste Quantity Chemical Reports for each of the nine parishes of Cancer Alley, which showed millions of pounds of toxic chemical releases that year, including releases of benzene, toluene, and xylene.[48] Petroleum is the primary source of benzene, a human carcinogen.[49] Benzene can harm the immune system[50] and cause anemia and nervous system damage. [51] The World Health Organization finds that there are no safe levels of benzene exposure.[52] Toluene can affect the central nervous system, causing short term headaches, and has immune, kidney, liver, and reproductive effects.[53] Exposure to benzene and toluene can cause increased risk for miscarriage, low birth weight, preterm birth, abnormal menstrual cycles, and difficulty conceiving.[54] Xylene can irritate eyes, nose, skin, and throat, cause headaches, and in high doses, death.[55]

Companies are required to report TRI emissions data to the EPA, which then makes the data public on its website. However, though companies report emitting millions of pounds of toxic chemicals in Cancer Alley each year, not all emissions are required to be reported and this self-reported data is routinely found to be undercounting actual emissions.[56] For example, oil refineries and petrochemical plants rarely install sensors to measure emissions (such as is required by US law for coal company smokestacks); instead, the data provided by most oil refineries and petrochemical plants is generally not based on actual real-time emissions but rather on predictions based on a single annualized sample, or entirely on mathematical models with no measured emissions.[57] Other operators are entirely exempt from these reporting requirements, including most fossil fuel extraction sites.[58] When real-world emissions are captured, they routinely find the industry-reported data oftentimes significantly undercounts actual toxic releases.[59]

Peter DeCarlo, an associate professor of environmental health and engineering at Johns Hopkins University in Maryland, studies atmospheric air pollution with applications to ambient air quality. He told Human Rights Watch that based on his experience, “It's almost expected that we would see higher emissions than are reported” by the companies, meaning that the TRI data are likely underestimating the actual exposure and health risks of people living and working in these areas.[60]

DeCarlo and his team recently performed measurements of emissions from fossil fuel and petrochemical plants in Cancer Alley. Preliminary unpublished results for releases of ethylene oxide, for example, which can cause respiratory irritation and lung injury, headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, shortness of breath, and cyanosis in association with acute exposure and which has been associated with the occurrence of cancer, reproductive effects, mutagenic changes, and neurotoxicity with chronic exposure[61] were in significantly higher concentrations than what was reported by the companies to the EPA, DeCarlo explained.

Since 2018, the EPA has required oil refineries to install fenceline monitors that measure benzene at their perimeters where the emissions can reach communities. Data from these monitors show that company reports have underestimated actual benzene emissions by as much as 28-fold.[62] Out of thousands of petrochemical plants nationwide, only 13 have had to install similar monitors as a result of federal action. Only four of these have provided enough data to be of use, revealing two plants, including one in Cancer Alley, with benzene emissions that exceeded EPA regulations.[63]

Cancer Alley fossil fuel and petrochemical plants also pollute groundwater and release pollutants into the Mississippi River, the primary drinking water source for the region.

Six of the 10 largest sources of industrial water pollution in Louisiana are in Cancer Alley and include one oil refinery and five petrochemical plants (including chemical fertilizer manufacturers, the primary feedstock of which is fossil fuels).[64] Cancer Alley refineries are also among the top 10 most polluting refineries nationally for the amount of selenium, nickel, nitrogen and “total dissolved solids” released into waterways. From 2019 to 2021, only one of the five oil refineries operating in Cancer Alley was in compliance with Clean Water Act regulations throughout all three years.[65] Louisiana ranks fourth among all states for total and most toxic water releases by industry, including releases of cancer-causing chemicals and those known to have reproductive effects.[66]

PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, have been found in water quality testing in Cancer Alley, in one instance reaching as high as 268 times EPA safe drinking water levels.[67] PFAS are a group of manufactured chemicals that are typically fossil fuel derivatives. The CDC calls exposure to PFAS a “public health concern”[68] which could impact immune systems,[69] reproduction, thyroid, and liver function.[70] At over 1.6 million pounds, Louisiana has the second-highest amount of reported PFAS released by any state in the US in 2020, with the largest emissions from petrochemical plants in Cancer Alley.[71]

There is less data on toxic pollutants released into waterways than the air because there are fewer laws and reporting requirements for potential water pollution.[72] EPA water standards for oil refineries, for example, are weak and outdated: they have not been revised in nearly four decades[73] and apply to only a handful of known pollutants, excluding many that are commonly emitted from these facilities, including benzene, mercury, and lead.[74]

In addition to oil refineries and petrochemical plants, there are terminals and tank farms throughout Cancer Alley storing oil, gasoline, and other petroleum products in rows upon rows of gigantic cylinders towering some 40 to 50 feet high and ranging in diameter from some 70 feet to many times that size.[75] Human Rights Watch observed many residents’ homes virtually encircled by tanks, including in St. James’ 5th District, where 87 percent of residents are Black.

In a recent study, the New Orleans-based environmental organization Healthy Gulf finds that fossil fuel and petrochemical operations are the source of the majority of pollution events after storms.[76] In 2021 alone, Hurricane Ida[77] resulted in more than 2,200 oil, gas, and chemical pollution releases, including across large swaths of Cancer Alley. At least 171 oil spills and 1 million pounds of pollutants were released into the air, among other releases, from ruptured pipelines, refineries, petrochemical plants, tank farms, and LNG facilities across the state. Multiple refineries and chemical companies burned flares that formed large sooty black and orange flames, visible from many miles away, and “the sulfurous stench of rotten eggs pervaded for weeks after the storm.”[78] The study finds that without meaningful regulation and a transition off fossil fuels, this pollution trend identified over more than a decade from repeated storms, will worsen with the climate crisis.[79]

II. Findings

Everybody’s sick and dying and it just keeps getting worse.

— Dominic Kruger, 45, interviewed in Ascension Parish, May 16, 2023

Human Rights Watch investigated the impact of the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry on the health of residents of Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, and found communities facing cancer, maternal, reproductive, and newborn health harms, and severe respiratory ailments. They have had little ability to protect themselves from toxic pollution and insufficient recourse when polluters flouted laws. The response of government officials has ranged from inadequate to openly hostile. Death and disease permeate the area, with a disproportionate harm experienced by already marginalized communities of color, particularly those living closest to the plants.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 37 residents of Cancer Alley, seven of whom have been diagnosed with cancer, including breast, prostate, and liver cancers. All 37 residents report being impacted by cancer, which they describe as having ravaged their immediate families, loved ones, and members of their communities. Ten women shared their personal stories of maternal and reproductive health harms, while another dozen discussed those of immediate family members, friends, or neighbors, including low-birth weight, preterm birth, miscarriage, stillbirths, high-risk pregnancy and birth, and infertility.

Severe respiratory ailments were extremely common, including chronic asthma, bronchitis and coughs, childhood asthma, and persistent sinus infections. Residents said these ailments added stress to already at-risk pregnancies, resulted in children being rushed to emergency rooms and kept inside to avoid polluted air, missed days of work and school, sleepless nights due to wracking coughs, and the deaths of family members and friends.

Human Rights Watch found both the state and federal governments are failing to protect the environment, health, and other human rights of Louisiana residents from harms caused by the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry.

The prevalence of harm indicates that authorities at both the state and federal level are failing to respect, protect, and fulfil the human rights to life, health, access to information, and freedom from discrimination on the basis on race.

Identifying the cause of increased prevalence of cancer in a community is complicated. There are many different types of cancer, most of which have a long incubation period between exposure to a carcinogen and detection, and individuals may be exposed to multiple carcinogens over many years. The definition of a “cancer cluster” appears straightforward (a “greater-than-expected number of cancer cases that occurs within a group of people in a geographic area over a period of time”), but in reality it is very — and far-too often prohibitively — difficult to prove.[80] In Cancer Alley, for example, the small size of communities located around a specific plant can make it difficult to attribute incidence of cancer to a specific toxic exposure.

Delaying action until a causal link has been established between exposure and disease, particularly in cases where it takes years for latent diseases to manifest themselves, can lead to preventable human rights harms, including death, while the pursuit of unachievable evidence is sought. This approach also risks turning scientific research into a battleground since one of the ways that business interests can most effectively stymie action is by challenging, blocking, or controlling research to undermine achieving a scientific consensus.[81]

Human rights law protects the rights to life and health. Access to clean air is essential for the enjoyment of these and other rights. The US government has a duty to prevent or regulate activities that pose risks to human rights. This duty can extend to activities that have not been conclusively shown to cause harm where there is good reason to believe that they may. Because of the varied health outcomes associated with environmental harms and the long period it may take for health impacts to manifest, federal and state authorities should take precautionary measures based on the best available science. They should also endeavor to carry out or support studies to identify the human rights risks in a definitive way.

The Human Health Toll

At 57, Angie Roberts carries herself like a much older woman. She moves with the care of someone who not only experiences frequent pain, but also worries that each movement will elicit more. Seated in her kitchen in St. James, husband Jerome and sister Valdez at her side, her grandson Peyton rushes by while her daughter, who works the night shift as a nurse, sleeps in the next room. Her son heads out the door in coveralls, cup in hand emblazoned with the name of the nearby petrochemical plant at which he’s temporarily working.

The shades are drawn tight as they are most days. The “view” outside is of rows upon rows of towering oil storage tanks barely a stone’s throw away. Their home sits at the end of a lane lined with hundreds of these massive tanks. Giant white pipelines crisscross the land. A train carrying fossil fuel products loudly lumbers by. Within a few miles are several other large fossil fuel and petrochemical operations.

They have lived here for 28 years.

The house was here first. The tank farms came later.

Roberts feels imprisoned. In 2019, she was diagnosed with breast cancer for which she underwent a mastectomy. Her doctor has now detected suspicious lumps in the remaining breast requiring regular mammography. She developed multiple sclerosis (fossil fuel and petrochemical emissions can increase the risk of autoimmune diseases such as MS[82]), suffers from severe bouts of coughing which force her awake at night gasping for air, and has constant skin rashes. She blames the pollution from the plants. She wants to leave. But the price they would get for their home, were anyone interested in buying, has made moving impossible.

“Who would want to live here now?” she asks in dismay. “I’m dying here.”[83]

Human Health Risks from Fuel and Petrochemical Facilities in Louisiana

The Environmental Protection Agency’s Risk-Screening Environmental Indicators (RSEI) Model is used as a relative measure to compare overall risk to human health (cancer and noncancerous) of toxic chemical releases from certain industrial facilities.[84] Human Rights Watch found that, among facilities that report to the EPA, fossil fuel and petrochemical facilities were responsible for 97 percent of the potential risks to human health (RSEI burden) in Louisiana. Just those in Cancer Alley alone were responsible for almost all - or 84 percent - of the total RSEI burden for the whole state.[85] The map below shows the areas where fossil fuel and petrochemical facilities have the highest RSEI scores. [86]

Human Rights Watch aggregated all of the US RSEI scores at the census tract level (a small geographic area for which the US Census Bureau maintains statistical information).[87] There are 15 census tracts in Cancer Alley that are at the 99th percentile in the country for RSEI scores. Another 18 tracts are between the 90th and 99th percentile. A total of over 124,000 people live in these tracts. This means that residents of Cancer Alley face among the highest estimated risks of cancer and other severe health ailments in the nation as a result of the emissions from fossil fuel and petrochemical facilities.[88]

Cancer

Kaitlyn Joshua, 31, grew up in Baton Rouge and today lives in Geismar in Ascension Parish. She remembers in her youth hearing a lot more resistance by local community members to the term “Cancer Alley.” “But it’s wearing off,” she said. She has lost four great aunts to cancer, and the recent passing of both of her grandparents (from non-cancer ailments) weighed heavily on her mind. Joshua blames the fossil fuel and petrochemical plants that her aunts and grandparents lived next to in Baton Rouge their entire lives for their deaths. “It’s this very real experience of folks just dropping with it left and right,” that changed minds as more people came to realize, “People are getting cancer diagnoses as a result of industry being so close to our homes,” Joshua said.[89]

Until a few years ago, Genevieve Butler, 66, lived not far from Angie Roberts in St. James. Butler also had breast cancer and a mastectomy, as did nearby resident Janice Ferchaud. Her neighbor, Brenda Bryant, 76, is also a breast cancer survivor, treated with radiation therapy.[90] Bryant's brother and next-door neighbor, Leroy Frazier, 69, has prostate cancer.[91] Gail LeBoeuf lives in Convent, across the Mississippi River, and was diagnosed with liver cancer in January 2023.[92] Younger women told Human Rights Watch they had lumpectomies and hysterectomies as precautions against developing cancer.

Raven Taylor grew up in St. John Parish and has had three lumpectomies to remove abnormal breast tissue.[93] Ashley Gaignard lives in Ascension Parish and has also had three lumpectomies. Two were found to be benign and one was malignant and required treatment.[94]

Twin sisters Jo and Joy Banner, 44, live in Wallace on the east bank of the Mississippi in St. John Parish. Their male cousin lived near and worked in the petrochemical plants for years before being diagnosed with breast cancer. He had a double mastectomy.[95]

According to EPA data, nearly every census tract in Cancer Alley ranks in the top 5 percent nationally for cancer risk from toxic air pollution.[96] The census tract in St. John where Robert Taylor’s home sits and in which his children, including daughters Raven and Tish grew up, has the highest cancer risk in the US from toxic air pollution, more than seven times the national average.[97]

The EPA finds that from 2014 through to 2018, the average estimated lifetime cancer risk from air toxics for residents of Cancer Alley was more than twice that of residents in other parts of Louisiana and that the highest cancer risk falls disproportionately on Cancer Alley’s Black residents. The EPA concludes, “Critically, based on the data EPA has reviewed thus far, Black residents of the Industrial Corridor Parishes continue to bear disproportionate elevated risks of developing cancer from exposure to current levels of toxic air pollution.”[98] (“Industrial Corridor” is sometimes used by government agencies to refer to Cancer Alley.) The EPA lists cancers linked to the specific emissions from petrochemical and fossil fuel operations in Cancer Alley, including lymphoma, leukemia, breast cancer, and liver cancer.[99]

The EPA finds that Black residents in St. John Parish face an increased risk of cancer due to petrochemical operations where they live. The EPA has raised particular concern about Fifth Ward Elementary School, finding that the children who attend the school on the fenceline of a massive petrochemical complex face an “increased lifetime cancer risk” due to the average annual concentration of toxic air emissions they are exposed to.[100]

Just blocks away from Fifth Ward Elementary, Robert Taylor, 83, stands in front of his home and looks up and down the block, naming people struck by cancer. After a few minutes he gives up in exhaustion, saying, “There is no one who hasn’t had at least one family member who has died, in most cases, it’s two or more.” [101] It seems easier to name who does not have a personal experience with cancer, but Taylor draws a blank, and instead starts to go through his own lengthy family list of people who have had cancer, starting with his wife. The cemetery where many of his family members reside is sandwiched between two nearby plants. Taylor's home was made uninhabitable by Hurricane Ida. His son and niece live in a trailer parked on the front yard while they try to rebuild, and Taylor lives nearby with his daughter, Tish. In 2016, Robert Taylor founded a nonprofit organization, Concerned Citizens of St. John, to advocate on behalf of residents.

Geraldine Watkins, 81, lives not far from the Taylors. “My grandson died of cancer at age 30,” she told Human Rights Watch, adding, “I’ve had more than 30 family members [that died], they died of throat cancer. They died of leukemia… You don’t just shrivel up, you know, it takes time for the body to disintegrate. There’s been breast cancer, there’s been testicular cancer, there’s been liver cancer. The cirrhosis of the liver — never drank alcohol. It's lung cancer — didn’t smoke a cigarette, didn’t work at the plants.”[102]

Barbara Washington can personally name some 50 people who have died of cancer from her small community of Convent across the river on the east bank of the Mississippi in St. James Parish. Her list includes her sister. The two lived on the same lane on land originally purchased in 1874 by their great-great-great-grandmother Harriet Jones, who had been enslaved at a nearby plantation. Washington’s sister worked multiple jobs, including the night shift as a cleaning person for petrochemical plants. At age 56, she was diagnosed with stage four metastatic lung cancer. “She was not a smoker,” Washington quickly added. She died six months later. Cancer is a brutal way to die, and the chemotherapy was devastating. She died with her family gathered around her bed. As Washington looked down, her sadness was tinged with relief that her sister would no longer “have to be here suffering with us with all of this stuff going on.”[103]

Like most communities along River Road, Washington lives on a small single lane of modest homes and trailers on either side which ends abruptly, cut off by fields, plants, or train tracks. Some homes are up on cement blocks. Several have blue tarps waving in the wind, protecting roofs torn off in tornadoes and hurricanes. The street is quiet, with many homes empty, their residents unable to return because the damage is too extensive and they cannot afford repairs, or because the increased frequency and intensity of storms means they can no longer afford or even receive insurance.

A plant looms nearby. Not far in any distance there are many more. “The air doesn't stay in one place,” Washington said. “So, we’re getting it from all over. We’re getting it from the north, east, and west all around. We’re getting it.”

Seated around a table with friends Gail LeBoeuf, 72, and Myrtle Felton, 69, the three women discuss death.[104] A few years ago, they formed a non-profit advocacy organization, Inclusive Louisiana. Within just four months in 2014, Felton’s husband, sister-in-law and brother-in-law all died, her husband of respiratory illness and her brother-in-law and sister-in-law, spouses, of cancer. Later, another sister's husband died of brain cancer. The three women easily spend 20 minutes simply going through the cancer lists of nearby residents, friends, neighbors, and family.

In a 2003 report for the EPA, the National Academy of Public Administration concluded that from 1995-1999, the cancer rates for Cancer Alley were significantly higher overall than the rest of Louisiana and the US, and that the rates for Black residents were significantly higher than for whites in each area, as were mortality rates.[105]

The Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) denies that residents of Cancer Alley experience disproportionate burdens of pollution or adverse health outcomes, including cancer.[106] Spokesman Greg Langley recently said, “LDEQ does not use the term cancer alley. That term implies that there is a large geographic area that has higher cancer incidence than the state average. We have not seen higher cancer incidence over large areas of the industrial corridor between Baton Rouge and New Orleans.”[107]

Kimberly Terrell, a research scientist and director of community engagement at the Tulane University School of Law’s Environmental Law Clinic, told Human Rights Watch that Langley is wrong. The most relevant comparison is not the state of Louisiana, which has several areas with high concentrations of fossil fuel and petrochemical operations, but the US as a whole. More important, LDEQ is failing to account for proximity. Large swaths of the nine parishes that make up Cancer Alley do not have any industrial operations, having been spared these polluting industries for reasons which include systemic racism, she explains. Not only are the most polluting industries (fossil fuel and petrochemical operations) concentrated in Black communities, but they are permitted to emit an even greater scale of pollution. In a 2022 study, Terrell and co-author Gianna St. Julien found that from 2019 to 2021, LDEQ permitted industrial emissions of pollution that were 7- to 21-fold higher among Black communities than in predominately white communities.[108]

Those communities within Cancer Alley living closest to the plants — known as fenceline communities — face the worst pollution and the worst health risks and outcomes. Terrell, like the federal government, use census tract data (rather than parish-level), allowing researchers to focus on those people living in closest proximity to the plants.

The controversy can also lead to silence. “A lot of people around here don't like to talk about their sickness. A lot of people die and when they're dead, we find out that they died with cancer,” said Pastor Harry Joseph of Mount Triumph Baptist Church in St. James Parish.[109]

Maternal, Reproductive, and Newborn Health Harms

I cried the whole way from the hospital all the way to my house.

— Missie Bright, 44, Ascension Parish, describes her emotional response to experiencing a miscarriage while in her twenties, May 2023

Many of the residents of Cancer Alley Human Rights Watch interviewed experienced maternal, reproductive, and newborn health harms, and virtually all could name immediate family members, friends or neighbors who had, including low-birth weight, preterm birth, miscarriage, stillbirths, high risk pregnancy and birth, and infertility.

Premature birth (before 37 weeks of gestation) is the leading cause of death among infants in the US.[110] Low birthweight (less than 5.5 pounds) can cause serious health problems, including trouble eating, gaining weight, and fighting off infections. Both conditions can increase the odds of infant mortality due to cardiovascular, respiratory, and other diseases—harms which can persist through adolescence and into adulthood, and of physical birth impairments, particularly to the central nervous and cardiovascular systems.[111]

Ashley Gaignard, 46, was born and has spent her life in and around Donaldsonville, the parish seat of Ascension Parish.[112] Ascension Parish has the greatest amount of reported toxic air emission pollution in Cancer Alley, twice as much as the second highest parish. [113] With 22 existing, it will also have the largest number of fossil fuel and petrochemical operations in Cancer Alley, including fertilizer and pesticide chemical manufacturers, if nine newly proposed major emitting facilities are built. (East Baton Rouge, with 28 existing and two proposed such facilities, will have the second-highest number.).[114]

Gaignard has three adult children, all of whom were born at a low birth weight and two who were preterm pregnancies. Jason, 23, was born both preterm and low birthweight. He had an undeveloped lung which has contributed to lifelong severe asthma that is exacerbated by air pollution. By the second grade at Donaldsonville Elementary, he was restricted from recess because of frequent severe asthma attacks which required that he be rushed to the hospital in an ambulance. Trips to the hospital persisted through the sixth grade. He still must manage his asthma with nebulizer treatments and a pump.

Gaignard's oldest daughter, Tuezde, 27, was also born at a low birth weight and with sleep apnea which persisted through her first year of life.

Gaignard’s friend and colleague, Pam Ambeau, joined an interview conducted in Gaignard’s house by phone. Both women have had partial hysterectomies (as has Gaignard’s mother) and they described the procedure, which can be a preventative measure against the risk of cancer, as extremely common in Donaldsonville. The prevalence raises concerns for both women.[115] They also describe a large number of miscarriages in the community. Two of Gaignard’s sisters can no longer conceive, one of whom had a miscarriage and such a difficult pregnancy “that it almost killed her,” Gaignard said. Gaignard listed family, friends, and neighbors who have miscarried.

The association between reproductive health harms and the pollution from the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry “never dawned on me,” Gaignard said, adding that this information is not well-known in her community.

A new study presented for the first time in this report and currently under peer review for publication in Environmental Research: Health journal finds that Cancer Alley is among areas in the state in which exposure to high amounts of toxic air pollution is associated with a significantly increased risk of adverse birth outcomes.[116] The study notes that Louisiana has among the highest rates of low birthweight, preterm birth, and infant mortality in the US. It assessed birth outcomes in Louisiana between 2011 and 2020. Louisiana’s census tracts with the worst air pollution[117] had rates of low birthweight as high as 27 percent, more than double the state average (11.3 percent) and more than triple the US average (8.5 percent). They found preterm births were as high as 25.3 percent, far above the corresponding state and national averages (13 percent and 10.5 percent, respectively).

The most polluted census tracts in Louisiana had a 25 percent higher risk of preterm birth and a 36 percent higher risk of low birthweight compared to the least polluted tracts. The authors estimate that, on average, 2,166 low birthweight and 3,583 preterm births annually across Louisiana were attributable to toxic air pollution exposure. The regions with the highest rates of adverse birth outcomes corresponded to those areas with the highest pollution. These included Cancer Alley.[118]

Residents throughout Cancer Alley shared many other examples of maternal and reproductive health harms with Human Rights Watch. Angie Roberts in St. James has had two high risk pregnancies and births, one requiring an emergency C-section after which her daughter spent two weeks in the Intensive Care Unit.[119] Chasity White in St. James shared stories of family and friends who have experienced miscarriages.[120] Ke’Shawn Hicks is in his 20s and grew up near the fossil fuel petrochemical corridor in Baton Rouge. Two of his siblings were born premature, both of whom, like Hicks, had childhood asthma.[121]

Missie Bright has spent her entire life in Cancer Alley.[122] A single mother of two, she worked for several years in the petrochemical industry, describing dangerous work with a lasting harmful impact on her health. “I did what I had to do to raise my children,” she said. Bright now works for the Louisiana Just Recovery Network, advocating for green energy jobs and training and employing workers to help rebuild homes destroyed in hurricanes.

Bright suffered a miscarriage in her 20s, and like many other women, blamed herself. She was unaware prior to her Human Rights Watch interview of the risks associated with fossil fuel and petrochemical operations and maternal and reproductive health and that these can be compounding factors contributing to miscarriage.

Kaitlyn Joshua and her twin sister, Angelle Bradford, 31, grew up in Baton Rouge before moving to Ascension Parish. The twins and their brother continued to spend a great deal of time in their grandparents’ homes in Baton Rouge near the plants, including most summers. Both Joshua and Bradford have experienced reproductive health harms. Joshua explained that her asthma is exacerbated by and puts a strain on pregnancy.[123]

Joshua moved from Baton Rouge to Gonzales, and she now lives in Geismar in Ascension Parish, where “our literal backyard is a plant,” she said — one of many. Joshua was four months pregnant at the time of her interview with Human Rights Watch and was joined by her four-year-old daughter, Lauren. Joshua had also been pregnant in 2022, but at 11 weeks, she started experiencing severe pain and cramping, with such heavy bleeding and passage of tissue that her husband feared for her life. After two terrible weeks, in which they “couldn’t get the answers or health care” they sought, and during which heavy bleeding and piercing pains continued, she miscarried.

“I was really devastated for a long time,” Joshua said. After going public with her story in interviews with national media,[124] friends, family members, and people she didn’t know started reaching out, sharing their own experiences. “So many women in our circle have miscarried over the last couple years,” she said. “It wasn't until that story dropped that people, girls I know, were flooding my inbox. ‘Oh my God! This happened to me.’”

Shamell Lavigne, 46, Sharon Lavigne’s daughter, has spent her entire life in Cancer Alley, growing up in the small community of Welcome in St. James before first moving to Baton Rouge and then Gonzales.[125] The fossil fuel and petrochemical plants have been a constant presence, steadily expanding in size and number, Shamell tells Human Rights Watch. She has always lived or worked near these operations and describes their pollution as omnipresent, saying, “You can't escape it.”[126] Lavigne has fertility problems, suffering from insulin resistance and abnormal ovulation, and was told by her physician that she could not get pregnant. When she did get pregnant, only to suffer a miscarriage, she felt guilty and blamed herself, thinking that she had “picked up heavy boxes which must have been the cause.” She had not been told that there could be a connection between her reproductive health and her polluted environment.

Grateful for the birth of her daughter, Amerie Elizabeth, now an eight-year-old, she thinks aloud about the other women she knows in St. James who miscarried recently. It is yet another reason why the plants need to be shut down and held responsible for cleaning up the environment after they leave, she said. “You know, years ago I wouldn't have felt that way. But now that we know what they’re doing to our bodies,” and the number of people who are dying, “it’s just time,” Lavigne said.

Raven Taylor, 54 and a retired nurse, is Robert Taylor’s daughter. She was born and spent most of her life in St. John, where she was assigned to bedrest during a very difficult and highly at-risk pregnancy after which her uterus was removed. It was only the beginning of her difficulties. Her colon and stomach were later removed, and she had three lumpectomies. She suffered decades of surgeries and misdiagnoses while her health rapidly deteriorated before learning she had a rare autoimmune disease similar to Lupus called neuronal VGKC antibody syndrome. Fossil fuel and toxic chemical pollution emissions have been found to increase the risk of autoimmune disease.[127]

Taylor shares her anger and frustration that her physicians never asked about her environment nor suggested that she move. “I had to figure that out on my own,” she told Human Rights Watch, saying she did so only when “I began steadily losing body parts.”[128]

Taylor has weekly IVIG infusions via a port which goes directly into her heart. She is frail, tires easily, and concerned about infection, so she rarely leaves her New Orleans apartment, where she lives alone, missing out on time with her children and grandchildren. She spends a lot of time on the phone with her mother, who moved to California after she too became ill in St. John. “My mom was diagnosed with breast cancer and from breast cancer, she just went downhill getting more and more conditions,” she said, adding that their lives were “stolen” by industrial pollution from the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry.

Louisiana Bucket Brigade Chalmette Study The research of Terrell, St. Julien, and Wallace is supported by unpublished data from a 2004 household survey conducted by the environmental organization Louisiana Bucket Brigade. The survey, which used non-probabilistic sampling, was completed by 258 people in 124 households in the small community of Chalmette located just east of New Orleans and immediately adjacent to Cancer Alley and the site of two large fossil fuel facilities. Almost all respondents identified as white, 54 percent female, and with an average age of 47. A quarter of those surveyed had lived in their home for more than 20 years. Of those respondents who had been pregnant, 26 percent reported that they had had at least one miscarriage, far greater than the national rate at the time of approximately 15 percent.[129] Two women reported four miscarriages each and one woman reported six miscarriages. Thirty-five percent reported experiencing problems with a pregnancy.[130] St. Gabriel Miscarriage Study In 1990, Boston University epidemiologist Richard Clapp was hired by Louisiana’s attorney general to review a miscarriage study. In an interview with Human Rights Watch in June 2023, Clapp described the unpublished analysis, explaining that he and colleague Dan Wartenberg, a specialist in statistical methods, found that women living in Cancer Alley’s St. Gabriel, in Iberville Parish, and within a half mile of a petrochemical plant, had a significantly higher rate of miscarriage than national averages.[131] |

“My concern is for these young women who are now coming up behind me, that are living under the shadow of a petrochemical plant, the ones that can get out do get out. But there are so many that cannot move. And then here’s the deal in Louisiana, where are they gonna move to?” From one end of Cancer Alley to the other, “there are petrochemical plants!” said Debra Martin of Lutcher in St. James Parish.[132]

Respiratory Ailments

Can you please get my grandmother and grandfather out of Convent? Can you please find them a house, or they will die. It's getting too hard to breathe.

—Text message to Missie Bright, 44, Gonzales, from her son, May 2023

Almost all residents Human Rights Watch interviewed reported being diagnosed with or suffering from serious respiratory ailments. Severe asthma, chronic bronchitis, and chronic coughs are common, as are persistent sinus infections, headaches, shortness of breath, coughs, watery, itchy, and sore eyes, and nasal drip. Residents said these ailments added stress to already at-risk pregnancies, resulted in children regularly being rushed to emergency rooms in ambulances and kept inside to avoid polluted air, frequent missed days of work and school, sleepless nights due to wracking coughs, and the deaths of family members and friends. They described the stress of worry about their health and that of loved ones.

There is a well-established link between air pollution — in particular, the air pollution generated from fossil fuels — and respiratory disease.[133]

Human Rights Watch analyzed EPA TRI data and found that nearly 90 percent of Particulate Matter (PM 2.5) for which industry is the origin in Cancer Alley is from fossil fuel and petrochemical operations.[134]

Shortly after moving to Edgard in St. John, Imani Mathieu, 72, started experiencing watery and itchy eyes, coughing, nasal and respiratory issues requiring prescription medication. After five years, she was diagnosed with asthma for the first time in her life. She described extreme difficulty sleeping due to coughs and other breathing difficulties requiring the use of an asthma pump and nebulizer. “You know it’s not healthy at all,” she said of where she lives, adding that all of her respiratory issues are intensified when “the plants are polluting.”[135]