- Local authorities and Amhara forces in Western Tigray Zone in northern Ethiopia have continued an ethnic cleansing campaign against Tigrayans since the November 2, 2022, truce agreement.

- The Ethiopian government should suspend, investigate, and appropriately prosecute security forces and officials implicated in serious rights abuses in Western Tigray.

- International law provides that people forcibly removed from their homes have the right to return. However, the current context in Western Tigray is not conducive for voluntary, safe, and dignified returns.

(Nairobi) – Local authorities and Amhara forces in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region have continued to forcibly expel Tigrayans as part of an ethnic cleansing campaign in Western Tigray Zone since the November 2, 2022, truce agreement, Human Rights Watch said today. The Ethiopian government should suspend, investigate, and appropriately prosecute commanders and officials implicated in serious rights abuses in Western Tigray.

Since the outbreak of armed conflict in Tigray in November 2020, Amhara security forces and interim authorities have carried out a campaign of ethnic cleansing against the Tigrayan population in Western Tigray, committing war crimes and crimes against humanity. Recent Human Rights Watch research found that two officials, Col. Demeke Zewdu and Belay Ayalew, who were previously implicated in abuses, continue to be involved in arbitrary detention, torture, and forced deportations of Tigrayans.

“The November truce in northern Ethiopia has not brought about an end to the ethnic cleansing of Tigrayans in Western Tigray Zone,” said Laetitia Bader, deputy African director at Human Rights Watch. “If the Ethiopian government is really serious about ensuring justice for abuses, then it should stop opposing independent investigations into the atrocities in Western Tigray and hold abusive officials and commanders to account.”

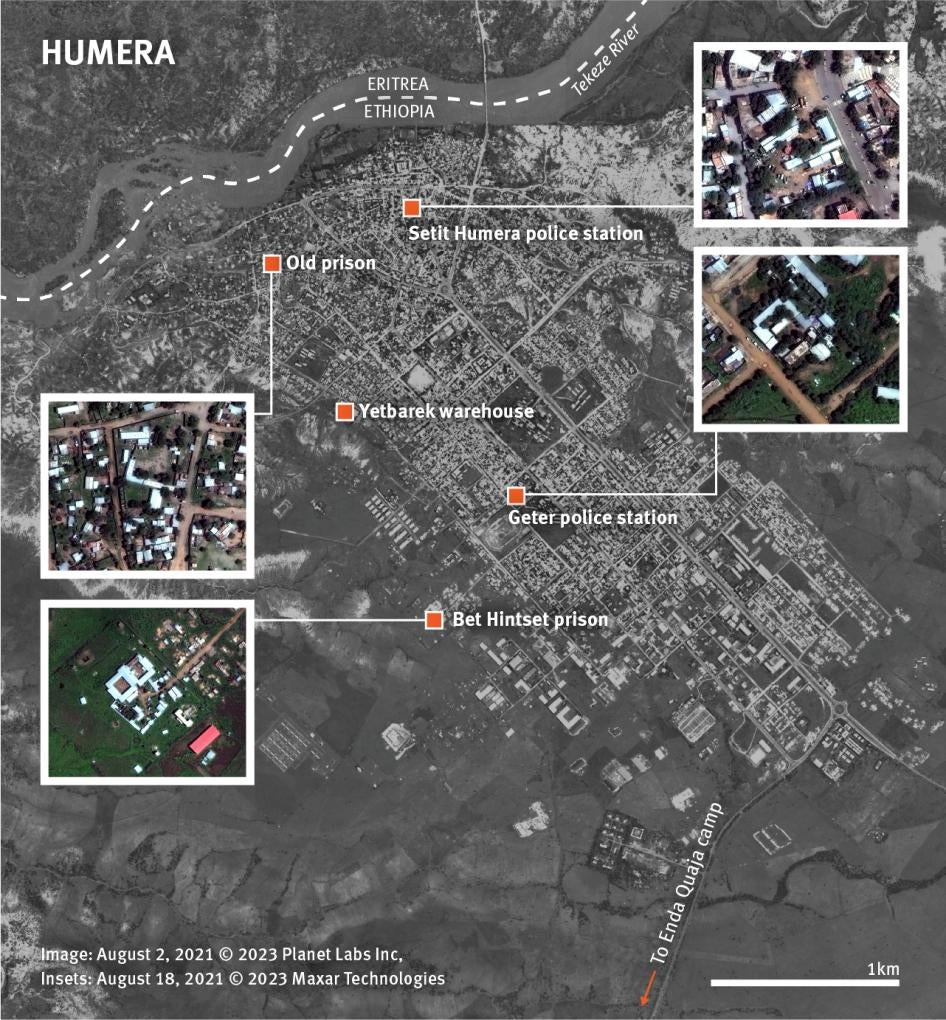

From September 2022 to April 2023, Human Rights Watch interviewed 35 people by phone, including witnesses and victims of abuses, and aid agency staff. Most are Tigrayan and had been arbitrarily detained in the town of Humera. Interviewees said that local authorities and Amhara forces held over a thousand Tigrayans in detention in the Western Tigray towns of Humera, Rawyan, and Adebai on the basis of their identity before forcibly expelling Tigrayans in November 2022 or January 2023. In May, Human Rights Watch provided a summary of its preliminary findings to the Ethiopian government but received no response.

Amhara regional special forces and Fano militia in Humera and Rawyan held Tigrayans in both official and unofficial detention sites in dire conditions. “There was no medical treatment,” said a 28-year-old who was detained in Bet Hintset prison in Humera. “If people got sick, they remained there until they die.” Many died due to lack of food and medication.

On the evening of November 9, Amhara forces and authorities in Western Tigray carried out the coordinated expulsion of detainees from sites around Humera and nearby towns to central Tigray. A report prepared by aid agencies found that Fano militia transported more than 2,800 men, women, and children from 5 detention sites in Western Tigray on November 10, according to Reuters.

Several former detainees told Human Rights Watch that again in early January 2023, at least 70 people, including residents and detainees, were forcibly expelled from Western Tigray.

Although the term ethnic cleansing is not formally defined under international law, the United Nations Commission of Experts, mandated to look into violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia, described it as a “purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means, the civilian population of another ethnic or religious group from certain geographic areas.” International law provides that people forcibly removed from their homes have the right to return. However, the current context in Western Tigray Zone is not conducive for voluntary, safe, and dignified returns of Tigrayan refugees and internally displaced people, Human Rights Watch said.

As of March, militias in Western Tigray continued to threaten and harass Tigrayan civilians. A woman from Adebai who fled toward Sudan, said: “The [militias] came into my home and said I need to leave because it’s not our land. They would knock at midnight and say Tigrayans can’t come back.” In April, three former and one current resident of Humera said that interim authorities were bringing in and settling communities from the Amhara region in the town, making it harder for Tigrayans to return.

Many displaced people told Human Rights Watch that they hoped to return home but did not feel safe while abusive officials and security forces remained. As of October 2022, the UN refugee agency had registered 47,000 Ethiopian refugees in eastern Sudan, with many reportedly displaced from Western Tigray. The precise figure of Tigrayans internally displaced from Western Tigray remains unknown. In 2021, hundreds of thousands were estimated to be internally displaced to other parts of the Tigray region outside of Western Zone.

Tigrayans interviewed expressed the need for justice and accountability. “Starting from the high officials all the way to those at the lowest level, the ordinary citizens that participated in criminal activities all need to be questioned, and accountability is needed,” said a 40-year-old man from Humera. “The international community and Ethiopian government need to work hard to make sure this never happens again.”

The Ethiopian government has demonstrated little interest in bringing those responsible for abuses in Western Tigray to justice. In September 2022, an Inter-Ministerial Task Force established by the Ministry of Justice reported that it would investigate violations in Western Tigray by December 2022. The government so far has not released details of these investigations nor held anyone responsible for serious violations.

In May, during Ethiopia’s review before the UN Committee against Torture, Ethiopian officials downplayed reports of ethnic cleansing. The committee said that the government should carry out prompt, impartial, and effective investigations into alleged human rights violations during the conflict in northern Ethiopia, and recommended that an independent body investigate allegations of torture and ill-treatment.

While the European Union, the United States, and other international partners have said that justice is a priority in Tigray, they are falling short of identifying explicit or concrete benchmarks for accountability for the atrocities against Tigrayans in Western Tigray, despite the near absence of independent investigations there to date, Human Rights Watch said. Instead, since the signing of the truce, many governments have sought a rapprochement with Ethiopian federal authorities rather than seeking tangible progress on accountability. In April, the EU Foreign Affairs Council adopted formal conclusions on its future engagement with Ethiopia but did not address the lack of progress on justice, including in Western Tigray.

International monitoring and investigations in Western Tigray remain critical, Human Rights Watch said. The African Union monitoring mission reported its plans to visit Western Tigray in June. Governments should continue to support the mandate of the UN International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia (ICHREE), established by the Human Rights Council, urge the Ethiopian government to cooperate with the commission, and scrutinize the Ethiopian government’s investigations in Western Tigray. Reengagement with Ethiopia should be tied to concrete progress on delivering justice and accountability for victims of violations.

The European Union should take the lead to ensure that the UN Human Rights Council renews the experts’ mandate at its 54th session in September 2023.

“Ethiopia’s international partners are eager to point to an improved rights situation, but this is out of sync with the lived reality many communities are facing,” Bader said. “If they truly want to see sustainable and credible rights progress, they should stop overlooking victims’ calls and press Ethiopian authorities to end ongoing abuses and investigate those leading the atrocities.”

For additional findings and details, please see below.

Ethnic Cleansing in Tigray

Since the outbreak of the armed conflict in northern Ethiopia in November 2020, a mix of Ethiopian security forces, in particular Amhara regional police, known as “Amhara Liyu,” militia groups known as “Fano,” and in some cases Ethiopian and Eritrean federal forces, have systematically rounded up thousands of ethnic Tigrayans. The security forces detained them for prolonged periods without charge in police stations, prisons, military camps, and other unofficial sites including warehouses and schools throughout the Western Tigray Zone. Hand in hand with these ethnically targeted arrests, security forces and interim authorities expelled in phases hundreds of thousands of Tigrayans toward central Tigray.

In an April 2022 report, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International documented that Amhara security forces and interim authorities had been ethnically cleansing the Tigrayan population in Western Tigray Zone in a campaign that amounted to war crimes and crimes against humanity. The organizations found that hundreds and perhaps thousands of Tigrayans were still detained and faced life-threatening treatment that may amount to the crime against humanity of extermination.

Since then, the authorities and security forces have held thousands of Tigrayans, mostly men, in sites that include administrative offices, police stations, military camps, and prisons. Most of the detainees interviewed had been held for over a year, since July or December 2021. Some were transferred from one site to another.

A 42-year-old man arrested in July 2021 and held in Bet Hintset prison in Humera said: “They arrested me because of my identity, because I am Tigrayan. At first, they said that we would be released after they asked questions to find out who is a criminal and who is not. But they didn’t do such a thing ... We were more or less 2,000 people in detention. We were all Tigrayans.”

Some said they managed to evade the ethnic cleansing campaign by hiding with Amhara friends or relatives, or concealing their Tigrayan identity. “People pretended to have a blood relationship with Amhara, Walqayte, or with Eritreans to save their lives,” said a 30-year-old woman, referring to other ethnic groups in Western Tigray. By August 2022, security forces apprehended many of those in hiding and eventually expelled them.

Bet Hintset prison was particularly overcrowded. “There were 2 blocks, one had around 1,000 people, the other around 900,” recalled one detainee who was held in a 12-by-4-meter cell with about 140 people. “Some rooms had 198 prisoners, others with 379. There was no space, it was really packed … All the rooms were full…. During the hot season, it was very difficult to sleep, so we would sleep in shifts.”

Guards limited Tigrayan detainees’ access to food, water, and medicine. A farmer held in an administrative center in Rawyan said: “We were around 60 and they didn’t give us any food. It was the people in Rawyan, other ethnicities that would bring us food. They were insulted when doing so. Sometimes we wouldn’t even eat.”

Former detainees in Bet Hintset said they were kept in overcrowded cells for months, with decreasing amounts of food and water. A detained farmer said: “They would sometimes give us three biscuits for a week. Sometimes they would disappear ... There was no medicine at all.” A 35-year-old man described June 2022 as a “dangerous month when the hunger climaxed.” Another detainee said: “The guards would say they were punishing us by denying us food. They wanted to finish us; they would repeatedly say we were a difficult people.” Detainees held in Badu Sidiste prison recalled similar deprivations.

Six detainees said that at least nineteen people died due to lack of food and medications in Bet Hintset prison alone between July 2021 and November 2022. From June 2022 onward, the already poor treatment and conditions detainees faced in Bet Hintset prison became worse when guards further reduced the limited food that detainees received.

Killings in Detention

Security forces killed at least six detainees in Bet Hintset prison in Humera between June and August 2022 following prisoner escapes.

Around mid-June, 16 detainees, most held in one cell, took advantage of heavy rains and managed to escape.

The guards, including Amhara regional special forces and Fano, learned of the escape the next day when they counted the prisoners. “They began interrogating us to find out how the people escaped and who helped them,” explained one detainee. “They started to beat and treat people badly.”

Two detainees said officials soon replaced the guards with more aggressive ones. A detained driver said, “They locked us in our room for one day and night.… They didn’t allow us to use the toilet. It was so hot.” Three witnessed the guards shoot and kill a man nicknamed “Bambini” three days later while he was using the toilet. The driver continued: “Maybe they imagined he might be escaping too. They beat and shot him with a Kalashnikov [military assault rifle] and brought his body before the prisoners to intimidate others.”

On August 15, 2022, a week before fighting resumed in the Tigray region, three prisoners escaped from Room No. 7 at Bet Hintset. Guards responded harshly by beating detainees in that cellblock. A detained farmer said: “They first locked us in our rooms. They beat us, hard, mostly those that acted as facilitators [detainees that acted as representatives between guards and other prisoners] in each room.” Guards then selected eight detainees from Room No. 7 for further interrogation. The farmer continued: “They took [eight] from the room people escaped from. I heard the beating and the cries and shouts of the people.”

Two of the men selected were Kahlayu Seyoum, described as 70 or older, who had worked as a teacher in the Amhara region, and the other, Seare Berihu, a religious scholar. The guards beat both and they died as a result, the people interviewed said. “The Amhara Liyu started to beat them severely with an iron rod. Kahlayu was ill with diabetes and had high blood pressure,” explained one detainee. “Seare immediately started bleeding from his mouth when they began beating them with an iron rod.”

Another detainee who witnessed their beatings added:

The [Amhara Liyu] started to beat them with sticks. But then one Amhara Liyu started criticizing the way they were beating them. She got out an iron rod and began beating them herself, hitting them in the chest. They began spitting out blood.

Another prisoner tried to help some of the detainees selected for interrogation but who survived the beatings:

They beat them with electric wire, an iron rod, in the back and front, the legs, even their eyes. I tried to get them medication because of the pain. It was usually impossible to get any medical assistance. There wasn’t such a thing. But we repeatedly begged. They finally allowed one woman outside the detention center to bring some anti-pain medicine so we could treat their wounds.

Four detainees said that a Fano militia member at the prison known as “Shiferaw” called a meeting a few days later and boasted about catching and killing one of the prisoners who had escaped. Shiferaw threatened to do the same to others who attempted to escape. One detainee recalled his threats:

Don’t try to escape. If you let one single prisoner escape, I will kill 10 of you. No one would question why I did this. No government official or body can question me. No one would accuse me. It is welcomed by God to kill you. It is not a sin to kill Tigrayans.

The bodies were dumped in shallow graves near a shed in the Bet Hintset prison compound or carted away, according to several detainees, including two who had been forced by guards to dig the graves inside the compound.

The August killings terrified some of the detainees. One 62-year-old man said: “I was afraid after this. Since then, we tried to convince others not to escape because we knew what the consequences would be.”

Torture and Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment

Amhara security forces, militias, and officials tortured, ill-treated, and subjected Tigrayan detainees to inhumane treatment, including beating them with iron pipes, electric wires, and sticks. In Badu Sidiste, a prison that also served as a camp for Amhara Liyu, detainees described being tied in stress positions for long periods, either at night or in the hot sun. “Our hands and legs were tied with a rope, and we were dragged outside in the sun where they beat us with sticks,” said one prisoner. “The [Fano and Amhara Liyu] would make us stay in the sun all day.”

One farmer held there for four months until his expulsion in January 2023 said he temporarily lost the ability to use his hands. “The guards tied our hands behind our backs for many, many days,” he said. “Because of this I couldn’t feed myself for one month. Other people had to help feed me.”

Detainees repeatedly identified Belay, a security official in Western Tigray, whom Human Rights Watch identified in its April 2022 joint report, as well as another official named Kassahun. They said Belay personally oversaw detention sites in Humera and Rawyan, issued instructions to guards, and took part in beating and interrogating detainees in Badu Sidiste prison. One detainee held in Badu Sidiste said he was beaten and interrogated by officials, including Belay and Kassahun:

[Belay and Kassahun] brought me out of the room. They tied my hands behind my back and started beating me. They hit me with their shoes. They asked me many questions, whether I was sending money to Sudan, or calling Sudan … and after many hours, I said “Yes, I would call my wife to hear my son’s voice in Tigray, and I would call my mother in Sudan.” I begged them to kill me, and they said no, you will die here from hunger.

A 26-year-old detainee held in an underground room in a military camp known as Enda Quaja, located south of Humera toward Rawyan town, said:

The hole was very wide and very dark. After many hours, they take us out to use the toilet. Coming out to the light would blind us. If they wanted to ask us questions, they would tie your arms behind your back and leave you in the sun. Because of this many became paralyzed, or their nerves are not working well.

A daily laborer held in Bet Hintset prison said the guards tormented the prisoners:

There was the time they selected 14 people. They took us to a narrow room without light, without enough air and left us in there all day. At night … two guards came and started insulting us. One was an Amhara Liyu who said, “It would be nice to kill all of you with this gun.”

Detainees also described mistreatment that caused lasting physical and mental harm. A 60-year-old farmer from Rawyan said his son was now blind after being held in a warehouse where berbere (Ethiopian spice blend) was ground. He said: “My son was detained there for 17 days, and then brought to prison with me. He is blind now because of the detention in the berbere warehouse and lack of medication.”

Enforced Disappearances

Family members and former detainees also raised concerns about the fate and whereabouts of detainees who were missing and feared forcibly disappeared.

One woman said the Fano militia, and Kassahun, the official, extorted payments from her for news about her husband, who was detained in August 2022. She said: “I sold my home property and paid 45,000 Ethiopian Birr [US$850], but they didn’t give me any information. Then after a month, they asked for 100,000 Ethiopian Birr [$1,900] to share information about his whereabouts so I could give him food.” By early January, Fano called her to the local government office in Humera town. “I hoped they would bring my husband so I could see him, so I could talk to him,” she said. That night, Fano expelled her to central Tigray. She has not seen or heard about her husband since.

On October 10, 2022, Belay and officials at Bet Hintset prison asked university educated Tigrayans to volunteer for “training.” One detainee described the desperation among prisoners: “The prisoners thought that they would die if they stayed. If they wanted to kill us, they could kill us anywhere, some said. So, people began registering.”

Another detainee explained the process: “Fifteen volunteered initially, but the officials said this was not enough. So, they called a meeting for the facilitators in each room and asked them to register those with university-level degrees or higher or they would do it forcibly. So, they started to go room and by room and registered people.” The authorities took 56 people away. The other detainees did not see them again and their whereabouts remain unknown.

Forcible Expulsions

Forced expulsions of Tigrayans from West Tigray Zone continued after the announcement of the “cessation of hostilities” agreement on November 2. Former detainees said that on the afternoon of November 9, Belay gathered detainees in Badu Sidiste prison for a meeting. “He spoke for one hour,” said one. “He said: ‘This is not your land. This doesn’t belong to you. We will send you to your land.’” Several detainees confirmed that Belay gave a similar speech at several detention sites in Humera on that same day, including Bet Hintset, Badu Sidiste, and Setit police station.

That night, guards gathered detainees at several sites, including Humera, Geter police station, and around Adebai, and beat detainees while forcing them onto dozens of Isuzu FSR medium-duty trucks, and then drove them toward Adi Asr and the northernmost Tekeze bridge, which separates Western Tigray from other parts of Tigray, where they were forcibly expelled. Former detainees said that at least two detainees were killed during the expulsions. One said: “They died not only because of beating, but because they were physically weak from the treatment in detention.” Three detainees added that the bodies were buried around the Tekeze river towards central Tigray, and in Sheraro town.

In January 2023, officials arranged further forcible expulsions of Tigrayan detainees and residents from Western Tigray, including from Badu Sidiste and other prisons. A 40-year-old man was among 11 detainees from Badu Sidiste and 60 others from other detention sites, including Setit and Geter police stations, expelled one night:

Belay and his colleague Kassahun came to the prison. They called me separately, they said we had decided to kill you, but now you are lucky, you and other prisoners have the opportunity to go to Tigray. They brought FSR trucks and sent us to Tekeze. After we reached the Tekeze, they told us to take the road until we reached “the place we deserved.”

By March, Tigrayans remaining in Adebai in Western Tigray felt they had no choice but to leave the town after facing continued threats and harassment. One woman who fled to Sudan in late March said:

The Fanos, and their leader named Belay, would say to us: “You are [Tigrayan], you used Western Tigray as much as possible, for 30 years, but now it is done. You have to leave this place. You can’t live or work here. We will not let you use it; you won’t eat food from here, what you have taken is enough for you.” They told us many times that we have to die of hunger.

Recommendations:

To the Ethiopian federal government and regional authorities:

- Suspend civilian officials, including interim Amhara officials, and security force personnel from the Amhara Special Forces and Ethiopian federal forces implicated in serious abuses in Western Tigray Zone pending investigations into their actions.

- Investigate serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law as appropriate, including the three people named in the Human Rights Watch/Amnesty International April 2022 report; Col. Demeke Zewdu, Commander Dejene Maru, and Belay Ayalew.

- Appropriately prosecute all those responsible for serious human rights abuses in Western Tigray and elsewhere.

- Facilitate access for independent human rights investigators to Western Tigray, including the International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia.

- Ensure that human rights monitors, including the national Ethiopian Human Rights Commission and the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, have access to Western Tigray and other conflict-affected areas, and regularly publicly report on their findings.

- Establish an independent body, in consultation with displaced communities and relevant UN agencies, that can organize and monitor returns that are safe, voluntary, well-informed, and dignified.

To the African Union

- Ensure that the AU Monitoring Mission publicly reports on protection concerns, rights abuses, and humanitarian access in Western Tigray during its proposed visit in June.

To Ethiopia’s partners:

- Consider imposing targeted financial and visa sanctions on individuals implicated in serious human rights abuses during the conflict in northern Ethiopia and since the truce.

- Monitor justice and accountability initiatives within Ethiopia and seek greater transparency on government investigations and accountability efforts.

- Assess reengagement with the Ethiopian federal government based on clear and specific indicators on accountability and justice for victims of serious abuses.

- Support the International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia (ICHREE), including by renewing the commission’s mandate at the UN Human Rights Council in September as in-depth, independent investigations into abuses carried out during the conflict remain essential.

- Support the creation of independent vetting mechanisms to ensure that federal and regional military and police personnel responsible for serious abuses are not reintegrated into the national army or police.