(ナイロビ)エリトリア政府はこの数カ月間、集中的な強制徴兵の動きの一環で、徴兵を忌避したとされる何千人もの人の家族を罰している、と本日ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは述べた。

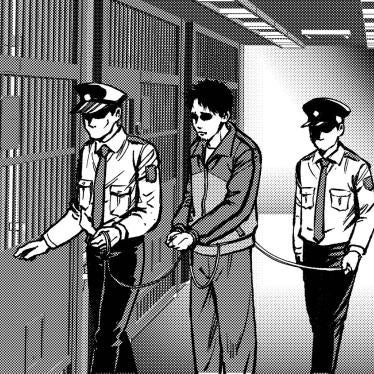

2020年11月にエチオピアのティグライ州で紛争が始まって以来、エリトリアの治安部隊はエチオピア政府を支援する作戦に深く関与しており、紛争中のなかでも最悪のものに入る人権侵害を行ってきた。エリトリア政府当局は徴兵忌避者や脱走兵と見なす人を見つけるためにエリトリアで何度も一斉逮捕を行っている。ティグライ州でエチオピアとエリトリアの勢力が合同で攻撃を行った2022年9月以来、エリトリア政府は抑圧を強め、徴兵や予備役召集を避けようとしている人の家族を集団懲罰し、高齢の男性を含めた大規模な強制動員を実施している。処罰には恣意的拘束や自宅からの強制退去が含まれる。

「エリトリア政府は戦闘要員である下士官の数を維持するのに苦労しており、徴兵忌避者や脱走兵と見なす人を見つけだそうと高齢者や幼い子どものいる女性を拘束したり、自宅から追い出したりしている」とヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチのアフリカ局長代理レティシア・ベイダーは述べた。「エリトリア政府は徴兵を拒否した人の家族に対する集団罰を直ちに止め、無慈悲な無期限の兵役義務体制(ミリタリーサービス)の改革に焦点を絞るべきである」

エリトリアには国民に無期限の兵役義務を負わせる政策があり、それには強制的な徴兵も含まれる。1998年から2001年までのエチオピアとの国境戦争そしてそれ以降、この政策はエリトリア政府の国民に対するより幅広い抑圧の中の特に中心に位置している。

法律上の18カ月という国民の兵役期間は無期限に延長され、40歳未満のすべての男女が政府の指示のもとで軍人または文民として働ける状態でいなければならない。実際には40歳以上の成人も兵役を強制されている。エリトリアは2018年にエチオピアと和平合意に至ったが、政府はこの抑圧的な制度の改革を拒んでいる。

いったん徴兵されると、まだ未成年である場合も含めて若い男女には除隊の可能性がほとんどない。国連調査委員会はこの徴兵制度を「奴隷化」と表現したが、これから逃がれると深刻な報復を受ける恐れがある。

ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは、最近エリトリアから逃げてきた人14人や強制徴兵や報復の対象となった人の親戚のほか、強制徴兵キャンペーンが行われたときにエリトリア国内にいた2人を含むジャーナリスト、その他の分析家11人にインタビューを行った。安全上の理由から、今もエリトリア国内にいる人にはインタビューを行わなかった。ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチはまた、2023年1月半ばまでにインタビューを受けた人の話の重要な部分を裏付ける衛星写真も確認した。2月には、ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチはティグライで戦うために送られた部隊の一部と、エリトリア国内の国境地帯にいた予備兵の一部が帰還した、との報告を受けた。

もっとも最近の徴兵キャンペーンは2022年半ばに始まり、当局は軍事訓練を逃れるために学校を退学した学生を含む徴兵忌避者と見なされる人のほか、すでに何年も従軍していた人も含む脱走兵が対象となった。さらに9月半ばには、政府は主に50歳から60 歳までの男性からなる予備兵を動員した。その多くは現役勤務から正式に除隊されたが武器の所持を続け、警備義務を果たすことを求められていた。9月17日、エリトリアの情報相はメディアに対し、予備兵の「ごく少数」だけが召集されていると述べ、全国民が召集されていることは否定した。

もっとも最近の動員キャンペーンでは、特に9月以降、治安部隊が都市部と農村部の至るところに検問所を設けた。治安部隊はさらに、各地方の関係者と協力して各戸を回った。政府の補助物品を入手できるクーポン券の取得資格を確認するという名目だったが、実際には徴兵忌避者を見つけるためでもあった。インタビューを受けた人たちによれば、治安部隊はこの戸別訪問を利用して、クーポン券制度上でその家にいるはずの家族の人数と、徴兵年齢に達した居住人の数とに不一致がないかも確認した。行方不明者を家族が探し出さなかったと当局が主張する場合、その家族は報復を受けることが多かった。

ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチの調査によれば、政府の捜索中は、高齢の親や、幼い子どものいる女性が数日間、または人によってはもっと長く拘束され、自宅から追い出された。71歳のある女性は、当局が探している彼女の息子のうち一人の居場所を明確に言うことができなかったために首都アスマラの自宅から立ち退かされた。

「母にはいくつか健康上の問題があるので、私の長男が出頭した後、近所の人たちが家から締め出さないでくれと当局に訴えようとした。でも次男が出てこなかったので、当局は家から締め出した」

同じく親戚が家から退去させられた国外在住のエリトリア人女性は「家の差し押さえはこれまで見たことがない。自暴自棄な行為だ」と述べた。

エチオピア連邦政府とティグライ当局との間で2022年11月に敵対行為停止の合意が結ばれたが、ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは、2023年初めになっても一斉逮捕や報復が続いているという報告を受け続けた。

アスマラ近くで一斉に捕まった徴兵忌避者とされる人の多くは、当初はアスマラの北東に位置し、軍が運営する悪名高いアディ・アベイト刑務所に連行された。ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチが分析した衛星写真には、2022年10月から2023年1月下旬までの間に刑務所の運動場に多数の人がいるのが写っている。親戚たちによれば、この時期に多くの男性が同刑務所から配属先の部隊の本部に連行された。

ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは予備兵がどこに連行されたかを確認することはできなかったが、アスマラで召集された数十人の予備兵がエチオピア国境に近いツォロナという町に連れて行かれたとの報告を受けた。

「誰もが、徴兵される危険があるという非常に恐ろしい気持ちでこれまでも常に生活してきたが、今回の状況はまったくレベルが違う」と、あるアスマラの住民は述べた。

兵役のための徴兵は、形式によっては国際人権法の下で認められている。しかしエリトリアは、参加しない人に不利益や罰を与えるという脅しを含む暴力的な手法や、親戚に対する集団的処罰を使っている。政府関係者は良心的兵役拒否の権利を尊重しておらず、徴兵の恣意的な実施や徴兵が無期限であることに異議を申し立てる機会を提供していない。これらの諸要因は人権侵害を構成する、とヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは述べた。国際人権法は、当該行為について責任のない個人に対し刑事責任を問うことを禁じている。

国際社会と周辺地域の関係者は、今も続く抑圧についてエリトリア指導部に対して具体的な対応を行い、国連人権理事会やアフリカ人権委員会、国連の専門家による継続した監視を確保するべきである。

国際社会と周辺地域の関係者は、エチオピア北部での深刻な人権侵害について責任のあるエリトリアその他の武装勢力に対するより幅広い対象限定制裁の一環として、エリトリア国内での深刻な人権侵害について責任のある個人や組織に対する対象限定制裁を、明確な人権指標と結びつけて採用・維持するべきである、とヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは述べた。「アフリカの角」や湾岸諸国を含むエリトリア周辺地域のパートナーは、エリトリア人に国外脱出を余儀なくさせ続けているエリトリアの暴力的な徴兵制度に意味ある変化をもたらすよう、エリトリア政府に圧力をかけるべきである。

「あらゆる社会階層のエリトリア人が政府の抑圧的戦術の矢面に立たされている」とベイダー局長代理は述べた。「エリトリア周辺地域のパートナーや国際的アクターは、激しい抑圧を止めるために行動するべきである」。

For detailed accounts and additional information, please see below.

Indefinite Forced Conscription and Eritrea’s Role in the Tigray War

Military training and national service are compulsory for all Eritreans, male and female, ages 18 to 40, and it is often indefinite despite provisions in Eritrean law limiting national service to 18 months. When the country’s 1998-2001 border war with Ethiopia broke out, former fighters and reservists who had been demobilized were forcibly conscripted and all national service recruits were retained under emergency directives. Conscription for many has continued to be extended indefinitely ever since, forcing many Eritreans, some under 18 and others above 40, into military service for years, some for decades.

Enforced indefinite conscription for many Eritreans starts during their final year of high school. Past Human Rights Watch reporting has documented that the Eritrean government forcibly channels thousands of young people, each year into military training even before they finish their schooling. Some of the students are still children, in violation of international standards. From here, people are sent either directly into military service or later national service.

The UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea found that “slavery-like” practices are routine within the national service system. Human Rights Watch has documented that during their prolonged conscription Eritreans, particularly those in the military, risk systematic abuse, including torture, harsh working conditions, and pay insufficient to support a family, which constitute illegal forced labor.

Human rights organizations have repeatedly documented that Eritreans who attempt to avoid conscription, including by dropping out of school, escaping from a military duty station, or fleeing the country risk punishment, notably arbitrary detention. In a 2009 report, Human Rights Watch documented that families of draft evaders were collectively punished usually by being jailed or forced to pay fines.

Conscientious objection is prohibited, and only rare exemptions are granted for people with a disability and, temporarily, on health grounds, although these exemptions are not systematically applied.

Since war broke out in Ethiopia’s northern Tigray region in November 2020, the Eritrean government has conducted waves of roundups, which intensified parallel to events in Tigray.

Eritrean forces had remained in parts of Tigray throughout the Ethiopian federal government’s five-month humanitarian truce, including in Western Tigray, until fighting broke out again in August 2022. Media reported that Tigrayan authorities accused Eritrea of a massive offensive in late September.

Within Tigray, Eritrean forces have committed large-scale massacres, pillaging, and the worst forms of sexual violence and targeted civilian infrastructure. They also killed and raped Eritrean refugees and destroyed two Eritrean refugee camps in Tigray.

Following a cessation of hostilities agreement, signed in South Africa on November 2, 2022, between the Ethiopian federal government and the Tigrayan authorities, the parties signed another declaration in Nairobi, Kenya, on November 12, stipulating that the Tigrayan forces’ handover of heavy weapons would be carried out in conjunction with the withdrawal of foreign and non-Ethiopian federal military forces from the region. In mid-January 2023, media reported on the withdrawal of Eritrean forces from key towns in central Tigray, notably the town of Shire. Yet reports of ongoing Eritrean force presence inside Tigray and ongoing abuses by Eritrean forces continue to emerge.

The European Union rolled out sanctions on Eritrea’s national security agency, headed by Maj. Gen. Abraha Kassa, for serious human rights abuses in Eritrea including killings, arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, and torture in March 2021. In September 2022, US President Joe Biden extended, sanctions for one year on Eritrean officials for serious human rights abuses in Tigray.

Collective Punishment of Families of Draft Evaders, Deserters

The government has intimidated and harassed people of all ages to pressure them into handing over missing relatives.

Relatives of those affected by the expulsions said that the government has confiscated homes of the parents of suspected draft evaders. This has left older people and women with children without a roof over their heads.

“My uncle was kicked out of his home,” said a woman whose uncle, about age 80, was evicted from his home in September by authorities looking for his daughter. “He’s now on the street. He’s homeless.”

A 71-year-old woman with chronic health issues was ejected from her home [in Asmara] in October when she was unable to locate one of her sons and was forced to seek shelter in an outdoor building with no lock.

The authorities have locked up the homes and put notices on the door.

Several people said that on occasion the local authorities threatened other people if they sheltered those evicted. “There is a standing order that no one can give shelter to those whose homes have been locked up,” said a man whose mother was ejected from her home. “This order was circulated by the local authorities.”

In early December, a 37-year-old woman was evicted from her home by local officials and military officers, following their search for her daughter who had refused to adhere to the call up. A relative said:

When she came to our home, they threatened her and my family. She wasn’t even able to stay one night. It was the local officials. They are watching. You can’t go to anyone’s house, it’s like a crime. She is living on the streets. Our relatives are sending her food there, but now authorities have told her she can’t stay on the streets. They threatened to send her to jail if she doesn’t send her daughter.

The authorities have also arbitrarily detained relatives of draft evaders in formal and informal facilities, including older people and people with health conditions.

In early September, a 78-year-old man was detained for three days in a village school because the authorities were looking for one of his sons. “My parents and nephew were given the option to lock up the house or for my father to be arrested,” said another son. “There was no warning.” None of the relatives were granted access to him during his detention.

There is no limit to how many members of a family can be conscripted. An 80-year-old man with diabetes was detained in early December for failing to bring forward the youngest of his six sons. His five older sons had already been conscripted.

Other Forms of Punishment

The authorities have also targeted people’s means of livelihood and income. Human Rights Watch received reports of government forces confiscating livestock in rural communities and preventing people from harvesting their crops to get people to hand themselves in, particularly in southern Eritrea in the first weeks of the campaign. Media reported that local administrations have also been withholding ration coupons from families whose members have not heeded the call. Two people said that their relatives’ shops were shut down to punish them for failing to hand over missing relatives.

Impact on Families

People described the significant toll of the collective punishment to Human Rights Watch.

“There is a lot of fear among the community, many people from all walks of life have gone into hiding,” said an Asmara resident.

“We don’t know if they [the authorities] are just doing this to terrorize people,” said a woman whose relatives have been targeted in the campaign. “They had left them [children and older people] in peace, but now they are trying anything to put pressure on them.”

A woman, whose relative was evicted from her home in Asmara, said:

People are afraid, you can’t help your relatives. That’s why people are giving up, they give their children, they give their husbands, as you can’t keep resisting.

Several other people said that they and their relatives are still willing to pay the price of protecting their loved ones. An older man, who was detained for three days after refusing to force his son to hand himself in, fell ill for several weeks after this detention, but the family remains resolute: “My brother is still in hiding, but we all support his decision,” said the brother who lives in exile.

Intensifying Forced Conscription Since Mid-2022

The government’s enforced conscription drives intensified during the summer. Human Rights Watch received reports of the drive starting in July 2022 in rural areas, notably in the country’s southern region around the town of Seghenyti, before intensifying in major towns including Asmara in mid-September through early 2023.

In mid-September 2022, the government also started recalling reservists, over age 50. The security forces set up checkpoints to verify whether people were exempt from military conscription and alongside the local administration conducted door-to-door searches in neighborhoods.

Local authorities keep track of people through a family coupon system, which specifies how many people are a part of the household and requires all family members to be there or to justify an absence in order to renew a family’s coupon. This system has played a central role in identifying alleged draft evaders during house-to-house searches.

“This is happening in literally every neighborhood in Asmara,” a resident said. “Every household that has a member who could be conscripted has been visited.”

People have also been rounded up from religious facilities. Reliable sources reported that on September 4, security forces detained young people attending a mass in a Roman Catholic church in Akrur, in the southern region. Human Rights Watch analyzed images posted online starting in early September appearing to show uniformed men rounding up young men and women outside of the Medhane-Alem Roman Catholic Church near Akrur, southeast of Asmara. Researchers were able to verify the locations shown in the images.

In October, three Roman Catholic priests were detained in separate incidents, including the bishop of Segheneity, Fikremariam Hagos Tsalim, who had called for peace in Tigray. The three were unlawfully held until their release in December.

Media have also reported that the authorities called for those previously exempted from military service to undergo new medical tests. However, Human Rights Watch received accounts of people with chronic health issues and disabilities, including injuries sustained during the 1998-2000 border war, being rounded up in the recent drive and sent off to military postings.

The conscription campaign has continued through early 2023, nearly three months after the cessation of hostilities in Tigray was signed.

Detention Sites

Relatives and observers said that many of those rounded up in Asmara of considered to be of conscription age have initially been taken to the infamous Adi Abeito prison on the northeastern outskirts of the capital then sent on to various military headquarters and other camps. Rights groups and the media have previously documented inhumane and degrading conditions and treatment in Adi Abeito. In 2021, the US-based Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) released a documentary with leaked footage that they said was from the facility that showed prisoners lying on top of each other, unable to stretch out, inside a warehouse and reported regular torture inside the compound.

Human Rights Watch reviewed dozens of satellite images captured between September 2022 and January 2023 over the three different prison compounds identified in the PBS documentary. Human Rights Watch independently confirmed the locations of the compounds that appear in the videos.

Human Rights Watch identified a substantial increase in the number of people in one of the courtyards of the Adi Abeito prison compound beginning in the end of October 2022. This increase was still visible as of January 23, 2023. The courtyard appears significantly overcrowded. People congregated in organized groups within the prison compound are also visible on satellite imagery in the same period.

An increase in the number of people in the adjacent courtyard, identified by PBS as the compound of the women’s prison, is observable on satellite imagery from the beginning of January.

In another courtyard of the prison compound, which the PBS documentary had identified as the area where prisoners are ill-treated and tortured, Human Rights Watch observed on satellite imagery, since mid-November 2022, that some courtyard areas are covered by tarpaulins. Human Rights Watch was not able to identify whether the number of people in this area increased.

While it is difficult to confirm where those rounded up and those called up were taken, several people told Human Rights Watch that reservists from Asmara were taken toward the border with Ethiopia around Tsorona, while some of the people of conscription age were initially taken to their units.

A man said that one of his two brothers evading the draft handed himself in:

The call up paper came a month ago exactly. My first brother turned himself in 16 days ago [mid-October] at the local administration in his locality. He stayed in Adi Abeito prison for 10 days. After that he was taken to his military unit base.

Two interviewees said reservists sent in the first roundups to the border were asked to bring their own rations and found very little when they arrived.

The BBC reported that some reservists were sent to the front lines. Videos that appeared on Tigrayan regional media outlets allegedly showed detained prisoners of war in Tigray, described as Eritrean soldiers, many of whom were older men.