- Rwanda-backed M23 rebels in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo have committed unlawful killings, rape, and other apparent war crimes since late 2022.

- The dire security situation has been compounded by martial law in the region and the collaboration of the Congolese army with various armed groups, mostly along ethnic lines.

- The United Nations Security Council should add M23 leaders, as well as Rwandan officials who are assisting this abusive armed group, to the council’s existing sanctions list.

(Nairobi) – Rwanda-backed M23 rebels in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo have committed unlawful killings, rape, and other apparent war crimes since late 2022, Human Rights Watch said today. Attacks with explosive weapons in populated areas of North Kivu province have killed and injured civilians, damaged infrastructure, and exacerbated an already dire humanitarian crisis. Armed groups opposing the M23 have also committed rape.

The Rwandan army has deployed troops to eastern Congo to provide direct military support to the M23, helping them expand control over Rutshuru and neighboring Masisi territories. The United Nations Security Council should add M23 leaders, as well as Rwandan officials who are assisting the abusive armed group, to the Council’s existing sanctions list.

“The M23’s unrelenting killings and rapes are bolstered by the military support Rwandan commanders provide the rebel armed group,” said Clémentine de Montjoye, Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Both Congo and Rwanda have an obligation to hold M23 commanders accountable for their crimes along with any Rwandan officials supporting them.

The M23 armed group includes soldiers who participated in a mutiny from the Congolese national army in 2012. The group’s senior commanders have a well-known history of serious abuses against civilians. The dire security situation has been compounded by two years of martial law in the region and the collaboration of the Congolese armed forces (Forces armées de la République démocratique du Congo, FARDC) with various armed groups, mostly along ethnic lines. The warring parties have increasingly appealed to ethnic loyalties, putting civilians in remote areas of North Kivu province at a heightened risk.

From March to May 2023, Human Rights Watch interviewed, in-person and by phone, 81 Congolese victims of abuses, family members, witnesses, local authorities, representatives of Congolese and international nongovernmental organizations, UN officials, and foreign diplomats. Human Rights Watch also verified, using satellite imagery, photos, and videos, the shelling and destruction of civilian infrastructure. Most of the abuses documented took place between November 2022 and March 2023.

Human Rights Watch documented 8 unlawful killings and 14 cases of rape by M23 fighters. Human Rights Watch also received credible reports of over a dozen other summary killings by M23 forces, but because of access and security constraints, could not independently corroborate them. In addition, seven people were killed and three injured in apparently indiscriminate shelling on populated areas in Kanombe, Kitchanga, and near Mushaki, during M23 attacks.

Survivors reported cases of M23 fighters raping women in front of their children and husbands, which adds to the trauma experienced by victims and erodes the social fabric of communities and families. Gang rapes were reported involving up to five assailants. Due to stigma and underreporting by survivors, the full number of incidents of sexual violence by armed groups is most likely much higher.

A 46-year-old mother of six, who fled Mushaki in Masisi territory on February 25 with her 75-year-old mother, ran into a group of 10 M23 rebels, who took their money. “They wanted to rape us,” she said. “My mother said no, so they shot a bullet into her chest, and she died on the spot. Then four of them raped me. As they were raping me, one said: ‘We’ve come from Rwanda to destroy you.’”

Survivors and witnesses identified M23 fighters on the basis of their uniforms and equipment, in some cases with the help of photographs published by the UN Group of Experts on Congo. Some victims said that M23 rebels identified themselves as such or said they had come from Rwanda.

Human Rights Watch also documented six cases of rape by rebels linked to other armed groups, including the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda, FDLR), a largely Rwandan Hutu armed group, some of whose leaders took part in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, and the Nyatura Abazungu.

M23 leaders have denied that their forces have committed any crimes. On June 6, Human Rights Watch spoke with an M23 spokesperson who said the armed group denied allegations that its forces have committed abuses.

The UN Group of Experts, that monitors the arms embargo and sanctions violations in Congo, independently presented compelling evidence of Rwandan support to the M23 rebels. The Rwandan government has denied these allegations.

On May 1, the East African Community (EAC) announced that its troops were deployed to “ensure observance of ceasefire and in addition overseeing the withdrawal of armed groups.” The EAC and African Union-led political processes should ensure that adequate humanitarian aid is provided to those in need and that victims of abuse have access to justice, Human Rights Watch said.

The renewed hostilities involving the M23, the Congolese army, and various other armed groups have resulted in the displacement of about one million people since March 2022. On May 9, 2023, the aid organization Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, or Doctors without Borders) said it had provided care to 674 survivors of sexual violence in the last two weeks of April in camps for displaced people around Goma, the North Kivu provincial capital, a dramatic increase from previous reporting periods. Sexual violence against women and girls is widespread and not limited to areas of fighting. In many of the cases reported to MSF, women and girls were raped while searching for food or firewood around displacement camps.

Most of the victims of sexual violence interviewed by Human Rights Watch did not receive any medical treatment.

A humanitarian aid official working in North Kivu described the situation as “catastrophic,” adding that established displaced persons camps were only receiving the “absolute bare minimum” of support. “[Meanwhile,] all along the road to Sake, makeshift camps housing up to 15,000 people each have appeared, and they have no latrines, shelter, no water, and no health care,” the aid official said. “There is no one working there.”

The Congolese government with the support of international donors should urgently provide medical, mental health, and socioeconomic services for displaced people and survivors of sexual violence in the regions affected by the violence, Human Rights Watch said.

“The African Union and United Nations should intensify efforts to help the Congolese government to better protect civilians at risk from attack,” de Montjoye said. “The United Nations should impose targeted sanctions on those assisting the M23 and other abusive forces. Foreign governments currently providing military assistance to Rwanda should recognize that they too may be complicit in rebel atrocities.”

For additional details about M23 abuses and the recent violence, please see below.

The resurgence of the M23 rebel group since late 2021 led several Congolese armed groups to form a coalition in opposition. These militias are typically organized along ethnic lines, and some were previously rivals. By August 2022, most had returned to their respective strongholds. But following the M23 offensive in late October 2022 and its advance into the Bwito chefferie (chiefdom) and Masisi territory, the coalition resurfaced. It took on a prominent role on the front line of the fighting with the apparent backing of some senior Congolese army officers.

The M23’s renewed military operations and abuses have stoked ethnic hatred against the Congolese Tutsi community, whom many Congolese in North Kivu consider supporters of the M23, a largely Tutsi-led armed group. Human Rights Watch has documented several instances in which people from an ethnic Tutsi background or simply perceived as Tutsi or Rwandan faced hostility, threats and attacks by ethnic-based militia and the communities they claim to represent.

On December 15, United States Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that Rwanda should “use its influence with M23 to encourage” them to withdraw and to “pull back” their forces. Belgium, France, and Germany have also urged Rwanda to stop assisting the M23. Because Rwandan-supplied arms are contributing to M23’s widespread and systematic abuses against the civilian population, governments providing military assistance to Rwanda, such as the US and France, should suspend that support. The EU should ensure that its recent assistance to the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) mission in northern Mozambique is adequately monitored so that the EU is not contributing indirectly to abusive military operations in eastern Congo.

Any support by the EU or foreign governments to troops deployed by the EAC or its member states should be provided only on condition of development of a vetting mechanism in line with international standards, a strong protection mandate and due diligence policy, and the development of a human rights monitoring mechanism.

The UN sanctions committee should immediately seek additional information on M23 leaders and Rwandan military officers with a view to adopting targeted sanctions against them. The EU and others should maintain and expand sanctions against senior M23 commanders, leaders of other armed groups, and senior officials from across the region who have been found responsible for or complicit in recent serious abuses by their forces or those for which they have command responsibility.

The armed conflict in eastern Congo is bound by international humanitarian law, or the laws of war, including Common Article 3, Protocol II to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, and customary international law, which prohibit summary executions, rape and other sexual violence, pillage, forced recruitment, and other abuses. Serious laws-of-war violations committed with criminal intent – deliberately or recklessly – are war crimes. Commanders may be criminally responsible for war crimes by their forces if they knew or should have known about such crimes and failed to prevent them or punish those responsible. Rwandan officials may be complicit in war crimes through their military assistance to M23 forces.

Killing, Rape by the M23

Human Rights Watch documented killings and rapes by M23 rebels targeting civilians caught up in the fighting between the M23 and Congolese forces as they tried to flee to safety.

In Kanombe, which M23 forces captured in August 2022, former residents said that several hundred armed M23 fighters entered the town wearing military uniforms, sometimes with RDF insignia, and body armor.

“[The M23 told us:] ‘Anyone who is against us will die. We are not coming to fight, we are here to take back our land,’” said a former Kanombe resident who lived under M23 occupation before fleeing in January. “After they arrived, the M23 raped women, forced people to work for them, and beat people up, … “[W]e had to work in our fields and give them our crops.”

Three former residents described the execution of a man in November. “He went to the fields to get food without permission and the M23 killed him; he was 31 years old,” said one. “We found his body in the field later.”

A 22-year-old woman who fled Kitchanga in February, several weeks after the M23 took the town, described life under their control:

The M23 harassed people and looted houses. They took what they wanted and took men away. I don’t know where they took them…. After two weeks, they started raping women. They didn’t care if we were married or not. They came to my house in the evening on February 20. They told my husband to leave. There were seven of them, and five raped me. My husband couldn’t stand what happened to me and left me. I had to flee on my own, through the forest.

A 28-year-old woman described being gang raped in early January by M23 fighters who had occupied the town of Kako, Rutshuru territory:

After my husband left to go to work, five men came and knocked on my door around 10 a.m…. They said they were M23 and asked me if I was married. I said yes. They all raped me. I screamed but my neighbors were too afraid to come in.

Her husband came home but she heard her neighbors tell him not to come in or they would kill him. She said:

I offered them money, they said no. I asked for forgiveness. But they still held down my hands and legs and raped me until I lost consciousness…. Now I am pregnant, and I don’t know whose baby it is. I am so ashamed. Now my husband has left for good.

A woman, 37, and her husband, 36, who fled the fighting around Kitchanga on January 19, said that about a dozen M23 fighters intercepted them and seven others, including three women. The fighters tied up the men and executed one, said the couple. “They accused us of being FDLR and said we were collaborating with killers,” said the husband. They took the women further away and raped them.

The wife said: “They tore my clothes, I was crying and begging them to kill me rather than rape me. They raped me one by one; I was screaming so much. As the third one was raping me, I lost consciousness.” The soldiers tied the men to trees and severely beat them. Eventually, the husband was able to run away. Two of the men who managed to escape later found the wife.

On February 10, as M23 fighters surrounded the town of Mushaki, in Masisi territory, they shot at fleeing civilians, killing a 62-year-old man. The man’s wife said:

We knew the government troops were fighting M23.… [M23 were following us and] when we got to a place called “Volcan,” my husband was shot in the back. He dropped dead and I couldn’t stay because there were so many bullets being fired at us. I don’t even know if he’s been buried.

Shelling, Pillage of Civilian Areas

Human Rights Watch documented ten cases in which explosive weapons injured or killed civilians in Kitchanga and near Mushaki, in Masisi territory, and in Kanombe, in Rutshuru territory. In some of the incidents, it is not clear which military force was responsible for the attack.

Nine photos and videos that Human Rights Watch examined from Kitchanga show damage to houses and civilian infrastructure, including a hospital and a church, most likely caused by mortars and shoulder-fired rockets. The damage to the hospital and the church was also visible in satellite imagery.

A 32-year-old man from Kitchanga said that on January 20 a mortar shell struck his house, killing his three brothers and injuring his sister: “We were in the house preparing to flee when the round struck. Our house was next to a hospital. Many rounds fell and many people died.” Residents reported that M23 were attacking Kitchanga at the time and captured the town in the following days.

After fleeing to Karuba, a woman took refuge in her uncle’s house about 10 kilometers south of Mushaki. Fighting broke out between Congolese army forces and the M23. She said that although the Congolese army “had fled” around February 26, the M23 shelled the village, hitting her uncle’s house and killing her cousin and another man. Two people in Karuba confirmed the deaths. “I know nine people who died because of the M23 shelling,” said one of them. “We heard around 24 artillery shells fall on Karuba and its surrounding areas.”

A medical worker at a hospital near Sake said that between January and March, staff had treated dozens of victims with injuries caused mainly by shelling or gunfire. Two other medical workers in North Kivu said that medical centers had been overwhelmed with trauma victims.

People who lived in M23-occupied areas told Human Rights Watch that M23 combatants looted, destroyed, or set fire to property, forced people to work for them without pay, and abducted men for possible forced recruitment.

A 20-year-old woman from Kausa, in Masisi territory, said:

When they entered, they said they would target those who had protected the FARDC [Congolese army]…. [The M23] said that they were coming to take back their land, and that if we let the FARDC return they would kill us all. They forced men to carry their things and told them to join them. They looted houses and took our belongings.”

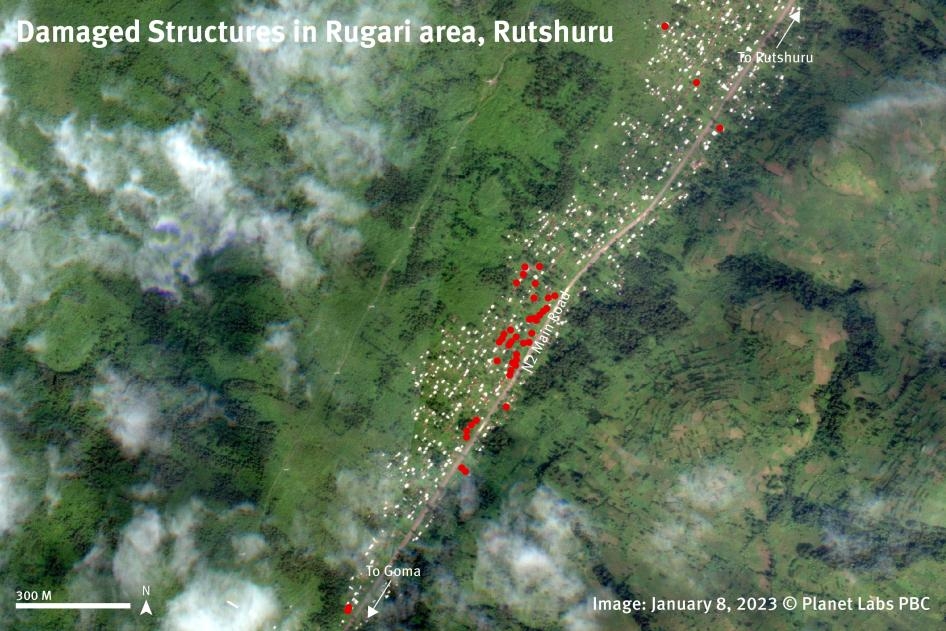

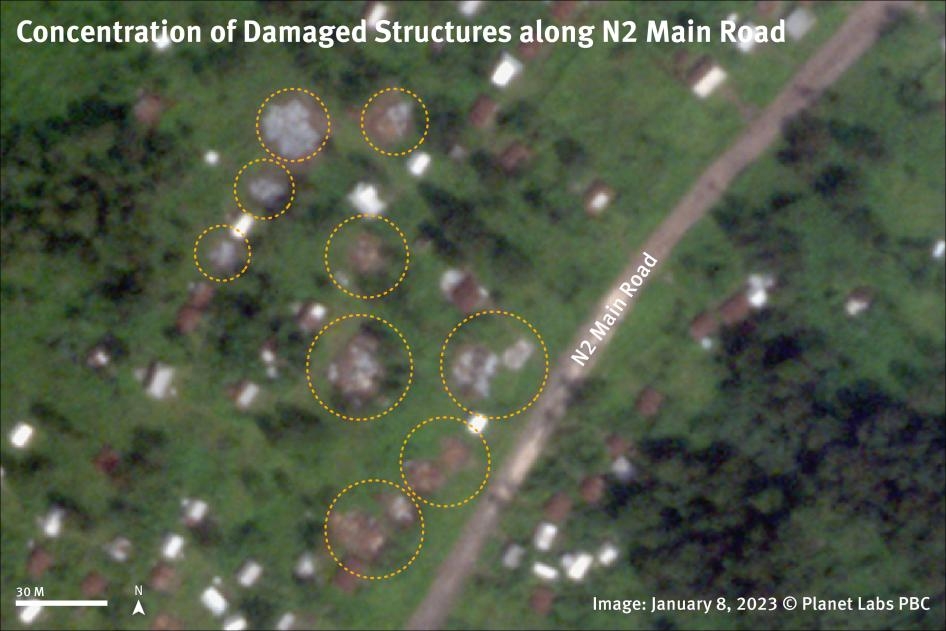

Residents in Rugari, a locality in Rutshuru territory which the M23 captured in late October, said that the rebels burned down and destroyed between 40 and 60 houses between October and January. They said that the rebels targeted houses they said belonged to other armed groups members. Satellite images that Human Rights Watch analyzed corroborate the destruction by fire of at least 40 structures along the N2 main road in Rugari area.

Rape by Other Armed Groups

Human Rights Watch has previously reported on Congolese army units that have supported armed groups implicated in serious abuses in the fighting with M23. Human Rights Watch interviewed six survivors of rape by armed groups, including the FDLR and the Nyatura Abazungu. In some cases, the attacks appeared to be retaliation against women who had been in M23-occupied areas.

A 60-year-old woman said that FDLR fighters raped her as she was hiding from the M23 in the forest near her home in Rugari, in Rutshuru territory. “The M23 arrived on the night of October 26. At 6 a.m. on October 27, a group of us went to hide in the forest,” about 10 women in all, she said. “Around 2 p.m., some FDLR found us hiding. They raped all of us.… I know they were FDLR because they are based in the Karambi forest near Rugari, and we know them…. They said they would kill us if we refused.”

A 35-year-old woman said she was raped while fleeing the M23’s arrival in Kitchanga with three of her children. In February, Nyatura Abazungu rebels stopped them at a checkpoint as they were making their way toward Karuba. “I saw two men being whipped, and then released. The rebels called me and told me I am an M23 supporter. I said it’s not true,” she said. “The others left, and a woman went ahead with my children…. I spent two hours trying to negotiate for them to let me go, in vain. One of them told me to follow him and took me to a little house, where he raped me. He said that if I resisted, he would kill me.”

A 30-year-old woman described her encounter with rebel fighters close to Kitchanga, while she and her husband fled the fighting. Her husband believed that the group was FDLR as they were wearing a mix of civilian clothing and Congolese army uniforms, and they were the only ones still in the forest fighting the M23. “They were armed and some had sticks,” he said. She said:

They asked my husband for money, and he lied and said he didn’t have any. When they searched him and found 100,000 Congolese Francs (US$45), they beat him up. Then three of them raped me. They untied the cloth holding my baby on my back and put him next to my other children. They cut open my clothes and one-by-one raped me in front of my children and my husband.

She saw a doctor at a health clinic near Goma, but said she still experiences intense pain. Her husband is seeing a counselor to recover from the trauma of witnessing the rape.

Congo’s government has an international legal obligation to investigate alleged war crimes on its territory and appropriately prosecute all those responsible. Congolese officers who assist armed groups that commit abuses can be held responsible for aiding war crimes.

Earlier M23 War Crimes

The M23 was originally made up of soldiers who participated in a mutiny from the Congolese national army in April and May 2012. These soldiers were previously members of the National Congress for the Defense of the People (Congrès national pour la défense du peuple, CNDP), a former Rwanda-backed rebel group. They claimed their mutiny was to protest the Congolese government’s failure to fully implement the March 23, 2009 peace agreement (hence the name M23), which had integrated them into the Congolese army.

In June 2012, the then-United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navi Pillay, described the M23’s leaders as “among the worst perpetrators of human rights abuses in [Congo], or in the world.” They included Gen. Bosco Ntaganda, who has since been convicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes and crimes against humanity when he led another armed group in Ituri province, and Col. Sultani Makenga, who is now referred to as “general” and has been leading the current offensive.

Human Rights Watch documented war crimes by M23 forces that, with support from Rwanda, took over large parts of North Kivu province in 2012. The Rwandan army deployed its troops to eastern Congo to directly support the M23 rebels in military operations.

UN investigators also said that Ugandan army commanders had sent troops and weapons to reinforce some M23 operations and assisted the group with recruiting. After the M23 briefly captured Goma, UN-backed government troops forced them back into Rwanda and Uganda in 2013.

Congolese authorities issued arrest warrants for Makenga and other UN-sanctioned M23 senior commanders in 2013. Rwanda and Uganda never acted on extradition requests to their countries.

Regional attempts over the past 10 years to demobilize M23 fighters have failed. The armed group resurfaced in November 2021, attacking Congo’s military forces, amid claims that Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi’s administration was not committed to existing peace agreements, including an amnesty for rank-and-file fighters. The agreements, however, did not address accountability for the worst human rights abusers.

On June 14, the spokesperson of the M23 sent Human Rights Watch a statement, dated June 10, denying that the armed group's forces had committed abuses documented in this report.